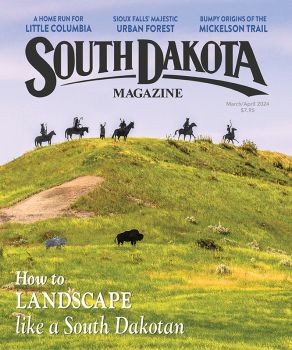

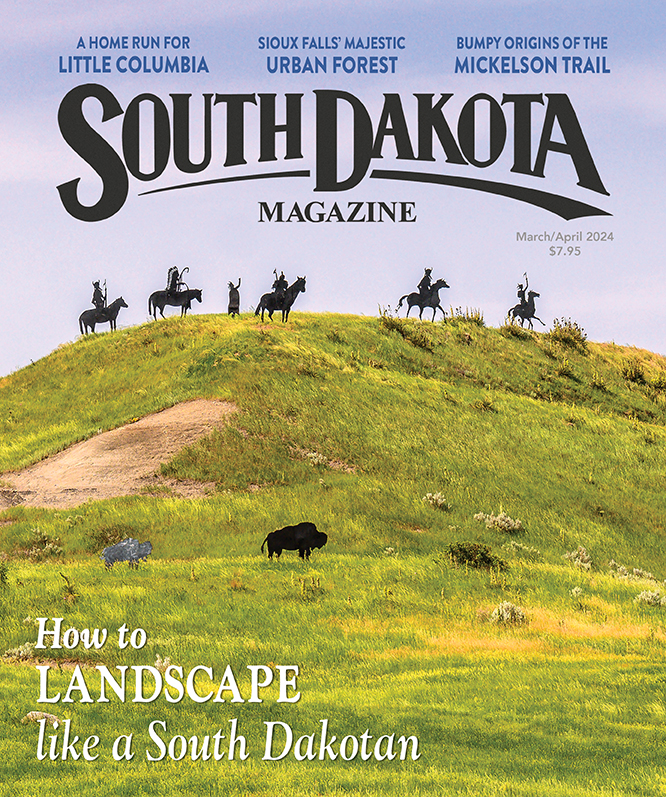

The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Bad Roads, Good Roads

|

| Near the town of Kidder, Marshall County. |

What a great idea. We’d cross South Dakota on gravel roads to see what we could find off the pavement. Maybe we could offer some tips to readers interested in a similar adventure?

A quick perusal of our Rand McNally Atlas & Gazetteer showed that it would be impossible to make such a trip east and west. West River has lots of dirt roads but it also has more curves and dead ends than a Black Hills cave. Going north and south from Nebraska to North Dakota across East River looked passable, however, with some careful zigzagging to avoid paved roads, lakes and East River dead ends.

The most feasible route, according to the Atlas & Gazetteer, would be from Bon Homme County to Marshall County. So off I went on a spring day with the atlas, a cooler of water, a camera and an 8-year-old grandson, Steven, for company.

We left at 8 a.m. on a glorious spring morning, the air freshened by a heavy rain that had fallen overnight. But what’s a little mud? We had a four-wheel-drive Jeep. Meadowlarks were singing and big black bulls were grazing belly-deep in brome grass. Steven and I could see Nebraska across the Missouri River. North we went on 424th Avenue.

The first official road in Dakota Territory was a dirt trail that ran from Yankton, the territorial capitol, to Smutty Bear’s Camp in Charles Mix County. Smutty Bear was one of the last holdouts on the 1858 treaty that allowed white settlement west of the Big Sioux River. As the story goes, Washington officials threatened to throw the old chief in the Atlantic Ocean if he wouldn’t sign; another version is that he was told he’d have to walk home from Washington.

The thought of walking home didn’t faze Smutty Bear even though there weren’t many roads west of the Mississippi. America was then more interested in rail development. Dakota Territory established a railroad commission in 1885, but a highway commission wasn’t formed for another 28 years.

|

| Tyranny Smart enjoys an evening walk along 424th Avenue, near the North Dakota border. |

However, decades before the invention of the automobile, politicians showed some vision for transportation. In 1866, Congress passed a law that allowed states and territories to claim public rights of way on lands in the West that were being opened to homesteading. The 1870 Dakota territorial legislature in Yankton acted on that authorization and declared that 66-foot strips dividing sections (square miles) should be established for the public.

When cars became available in the early 20th century, section line roads became a travel grid. In 1905, 10 years before he became governor and a champion of road building, Peter Norbeck bought a new Cadillac and drove it from Fort Pierre to the Black Hills on dirt roads.

State Representative Joseph Parmley of Ipswich introduced a bill two years later to make road construction the duty of county commissioners. His proposal was ridiculed and then defeated by fellow lawmakers. Undeterred, Parmley returned home and thought even bigger — he spearheaded development of The Yellowstone Trail, a dirt road that guided travelers from Minnesota’s Twin Cities to Yellowstone National Park.

The Yellowstone Trail became today’s Highway 12. Further south, business leaders promoted an east-west trail from Sioux Falls to Rapid City as the Custer Battlefield Highway. State workers smoothed the ruts with horse drawn drags in the 1920s. Gravel was added in 1928 and when concrete was laid in 1931 a “pavement dance” was held at Pumpkin Center near Wall Lake. That road is now Highway 16.

Thanks to the foresight of Norbeck, Parmley and many other pro-road politicians, South Dakota now has 83,609 miles of roads and 70 percent of them — 49,046 miles to be exact — are gravel. That doesn’t even count the 3,195 miles of dirt roads.

Most of South Dakota’s gravel roads never had a fancy name or a hard surface. However, they were numbered as streets and avenues 30 years ago in a statewide rural addressing program that has made life easier for hunters and fishermen exploring the back country, and for 911 dispatchers unacquainted with the red barns and lone trees that acted as landmarks prior to the green signs that now stand at every intersection. Rural streets run east and west in South Dakota while avenues are north and south.

Roger Holtzmann, South Dakota Magazine’s resident humorist, lives on a gravel intersection west of Yankton. He recently wrote that the addresses make it much easier to give directions to relatives: “If you needed to tell someone how to get to your farm you’d tell them, ‘Go to Wyoming, and when you’re 127 miles away from North Dakota, hang a right. Then go 391 miles east and you can’t miss us, a white house with green trim. If you hit Minnesota, you’ve gone too far.’”

The rural numbering system gave gravel roads very urbane names, but in many cases the street numbers might also be the traffic count for the year. Steven and I only met a dozen vehicles (10 pickups, one car and one big tractor) during our entire trip on gravel. So we were free to enjoy the sights. The first thing we noticed was a proliferation of red-winged blackbirds. Perched on cattails and fence posts, the chattering birds dominate every pond and swamp. Meadowlarks were singing from the street signs and an occasional rooster pheasant peeked his head from the wet grass, perhaps hoping to dry his feathers on the gravel.

|

| Presbyterian Cemetery, Bon Homme County. |

We also saw several modern-day reminders of southeast South Dakota’s diverse ethnic heritage. Our starting point was 312th Street and Colony Road, which leads to the Bon Homme Colony that was organized in 1874 and became the mother of all Hutterite colonies in North America. A few miles north of the colony, we came upon a Presbyterian Cemetery established by Czech settlers in 1878. A church they built of chalk rock was moved to nearby Tyndall in 1953, but a waist-high stone border surrounding the large cemetery is well preserved, as are its few hundred gravestones.

Our first challenge, I thought, might be to find a gravel crossing on the James River, but that’s not a problem. We approached the river on 423rd Avenue, and did have to detour east on a mile of “oil” on State Highway 44 (we knew we’d need to make a few east-west hard-surface corrections). We resumed the trip north on 424th Avenue and soon dipped into the river valley, where a concrete bridge provides a sturdy crossing. A large flock of swallows performed acrobatics over the muddy river. Steven had a fishing pole, so he made a few casts with a spinner. But the muddy water didn’t look like a northern fishery, so he quickly agreed to reel it in and we headed north.

At the intersection of 424th Avenue and 269th Street, we saw one tall gravestone in the corner of a cornfield. What a lonely place to be buried, especially compared to the well-tended Bohemian cemetery we’d just seen. The gray stone belongs to Abraham Bechthold and it includes this notation: Geboren 1880, Gestorben 1903. He was just 23 when he died.

“Why was he buried all alone?” wondered Steven.

History is everywhere along South Dakota’s gravel roads, but much of it is buried by graves and grass. Very visible, however is the changing face of agriculture. In the eight counties we traversed — Bon Homme, Hutchinson, Hanson, Miner, Kingsbury, Clark, Day and Marshall — the human exodus is harder to ignore than the chattering blackbirds.

All that remains of many family homesteads are a few rows of cedars or elms that served as a shelterbelt. Churches and schools are shuttered or gone. Even entire small towns have disappeared. Still, every acre of the land is tilled and seeded unless it’s too steep, wet or rocky for a tractor and planter. South Dakota farmers have remained true to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s definition of a good man, “that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till.” Nary an acre is wasted whether it’s along gravel or a concrete thoroughfare.

|

| Lone grave, Hanson County. |

Ironically, as the population dwindled the need for good roads increased. East River South Dakota is the western edge of America’s grain belt. The surviving farmers feed the world, and their machinery is bigger than some of the houses in which their grandparents lived.

County officials thought they were modernizing when they asphalted more than 13,000 miles of gravel roads in the 1950s and 1960s during the heyday of family farming. But today’s tractors can weigh up to 30 or 40 tons, and a semi-truck loaded with corn might be nearly as much. At that size, vehicles can wreak havoc on hard surface asphalt roads. It’s cheaper to maintain gravel, so many counties are grinding up asphalt roads and returning them to gravel. In some cases, they just let the asphalt crumble and go to weeds, giving some old roadways an apocalyptic appearance.

Dick Howard, a longtime road guru in Pierre, says there are differing attitudes about roads even within South Dakota. “The country roads still serve an important function in farming country, especially in those areas where we have ag development, dairies, grain transfer facilities and the big feedlots,” Howard says. “They need roads to move the products in and out. But when you go west of the river, where there are mainly cattle ranches, they don’t necessarily want roads every mile where people are running around in their pastures and have too much access.”

Howard’s theory is plainly illustrated in the Atlas & Gazetteer. Roadways in counties west of the river look like the crooked crease lines on your palm, while east of the Missouri the road system is a perfect grid, straight as a checkerboard.

Howard, now a mustached and affable lobbyist, has advocated for roads all his life. He served as the Secretary of Transportation for three governors and worked for the Association of County Commissioners and the Association of Towns and Townships. As Yogi Berra might have said, local government in South Dakota is 90 percent roads and 50 percent taxes. Howard has been on the front line of that paradox.

Everybody wants to live on a hard-surface road, quips Howard, but most of us want to pay for gravel.

A long trip on gravel demonstrates why rural residents — and their once-happy-to-oblige county officials — preferred asphalt or concrete over gravel. We started our journey slipping and sliding on muddy roads. After a few hours of sloshing our way, one could hardly tell that the Jeep was red. Despite the scarcity of vehicles, there are ruts on some of the poorer roads reminiscent of the wagon wheel tracks still visible in some native pastures. Ruts can outlast people and farms.

By afternoon, the hot sun dried the gravel and soon we were kicking up a trail of dust that seeped in the rear door of the Jeep. We zipped up the camera bag and covered it with a jacket to keep dust off the lenses.

A man could starve on gravel, so we diverted onto an oil road to eat at Carthage, a little town that gained attention for the welcome it gave to another traveler of the back roads. Chris McCandless abandoned his comfortable Virginia roots to hoof and hitchhike his way across the American West before stumbling onto Carthage, where he temporarily found work, friends and perhaps even a home. However, he soon resumed his wanderings and came to a bad end in Alaska. Moose hunters found his body in the Denali wilderness in August of 1992. McCandless’ story, including his brief respite in Carthage, was documented in the book Into the Wild. Denali’s rugged, remote and unforgiving nature seems further-than-the-moon away from Carthage, where a teenaged waitress laughed at Steven’s antics as he played hide-and-seek by the cash register.

Carthage also has a second link to literary history; it’s located at a place once known as the Bouchie Settlement, where author Laura Ingalls Wilder first taught school. She wrote about the experiences in her book Those Happy Golden Years. Heading north, it’s easy to imagine Wilder’s love for the region; even today the landscape is rich with tiny lakes and grassy fields. This is now lake country, a lowlands geography shaped 10,000 years ago by the last of the glaciers.

North of Carthage, 5 miles into Kingsbury County, we came upon Esmond, possibly the best-marked ghost town in the West. The town was platted on a treeless prairie of grass. Early residents debated whether to call it Sana or Esmond but the latter won. They constructed dozens of impressive buildings, but only a few remain standing. Small green signs with brief histories of the site mark the others.

|

| Esmond, Kingsbury County. |

Esmond is no longer treeless. The lots and yards where men and women gardened and painted and gossiped in the hot sun are now a shady forest. Lawns that had been mowed for generations have grown wild except at the United Methodist Church, a pretty white-frame chapel that still hosts Sunday services.

The church door was unlocked so Steven and I took a peek. He played a few reverent notes on the piano and signed the guest book. Can it be a ghost town if people still go to church there, he asked?

The glacial lakes have been a blessing to South Dakotans. They are rife with walleye and northerns. Beautiful homes circle the waters, and an important recreation industry has developed that includes not just hunting and fishing but boating, bird watching, hiking, camping and countless other activities.

The gravel roads of northeast South Dakota are vital for visitors who come to enjoy the outdoors, and there are some excellent routes. Driving on 425th Avenue west of Willow Lake on a dry, sunny summer afternoon is paradise. You wouldn’t mind if the road stretched all the way to Alaska.

But once you’re west of Willow Lake you might just as well throw away your Atlas & Gazetteer. Even a cell phone with Mapquest and Google apps will be of little help. The atlas shows that 428th Avenue should be passable, but within a mile we ran into water and a dead end. We reversed course and tried 427th Avenue, but the Froke/Waldo Waterfowl Production Area (WPA) shown in the atlas has grown. Another dead end.

And so we tried 425th Avenue and made some progress. But the road grid is now a maze. Soon you long for a road that will just take you a few miles and then provide an east or west outlet to another. Is that so much to ask?

423rd Avenue brought us to the western outskirts of Clark, but as soon as we passed the manicured country club we encountered more prairie potholes. We found our way to Crocker, pop. 18, saw water on two sides, and took 422nd, but it ended at another swelled lake.

The glacial lakes put South Dakota “on the atlas” so to speak for geese, mallards and numerous other winged creatures — even the dainty whooping cranes — who migrate across North America every spring and autumn. But the lakes and potholes expanded during a wet period in the 1990s, and that has made it nigh impossible to go any distance on the excellent gravel roads of Clark and Day counties, where the transportation budgets must have a line item for yellow “Dead End” and “No Travel Advised” signs.

|

| North Dakota border, Marshall County. |

Our predicament improved somewhat in Marshall County. We made tracks on 421st Avenue before it was interrupted, so we circled to the east because Steven had spotted a town name in the atlas called Spain, south of Britton. He was imagining bullfighters and taco chips, but all we found was a railroad track and a few dilapidated buildings. The ghosts of Esmond should erect some green signs in Spain.

As the sun began to set on our 12-hour trip, we came to an end on 422nd Avenue. We drove through Newark, another tiny hamlet, and came to 100th Street on the North Dakota border where a dirt path and a row of cottonwoods separate the twin states.

Google Maps estimates that the trip from Tyndall to Britton should take four hours. But who would want to drive straight through without stopping to dine, fish, worship, bird watch and enjoy the sights and history of South Dakota’s gravel roads?

Would we recommend such a trip to readers? Steven pointed to a cloud formation in the Marshall County sky as we were closing in on North Dakota. Clearly the clouds formed the letters NO.

Like a lot of things that are less than perfect, our gravel and dirt roads are best enjoyed in smaller doses. Get off the paved roads. But don’t try 212 miles (plus another 100 or so of zigzags) in a day.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2016 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments