The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Last Raft Trip Down ‘Old Mo’

Editor’s Note: Almost 64 years ago — before bulldozers dammed the Missouri and changed the river forever — two Sioux Falls men assembled a wooden raft and floated from Mobridge to Pierre. Durand Young and Tom Kilian wanted a last look at the wild waterway traveled by Lewis and Clark and other famous explorers. Kilian, a longtime education and community leader and founder of Kilian Community College, died in April 2014 at age 90. Young, a South Dakota journalist and executive with AAA, passed away in 2013 at age 86. In 1995, the two adventurers dug out their notes, journals and photographs and wrote this story about their five days on the river.

Aug. 3, 1956, 10:54 a.m.: Underway from point on east bank of Missouri, one-half mile south of highway bridge. Difficult to get raft in water. Difficult to steer for west side channel.

1:20 p.m.: Passed east tip of Blue Blanket Island.

So begins the official log of our five-day journey by raft down the Missouri River from Mobridge to Pierre. It was a memorable trek by two then-young native South Dakotans with a serious historical bent and a dash of Huckleberry Finn derring-do.

1956 marked the 150th anniversary of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s return trip to St. Louis. At the direction of President Thomas Jefferson, the explorers had gone up the Missouri in 1804, spent the winter in what would become central North Dakota, and then continued upstream to the origins of the Missouri, crossed the Rocky Mountains and descended the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. After an uncomfortable winter of 1805-06 on the Oregon coast, they completed their historic exploration of the Louisiana Purchase and returned to St. Louis.

We scheduled our raft trip to commemorate that anniversary year, hoping to stop at night near some of the same campsites Lewis and Clark had recorded 150 years before. And there would be little time left to see the Missouri as the explorers and their party had experienced it. The giant Oahe Dam would soon close off the riverbed and eventually pile up to 200 feet of water over the landscape from Pierre to Bismarck, N.D.

We spent many evening hours planning the trip — securing and studying old river maps and reviewing the Lewis and Clark journals and stories of other early travelers on the Missouri as well as designing our 8-by-12-foot raft. Determined to experience the river in its natural state, we disdained a motor. The free flowing current would be our power and, as we found out along the way, would sometimes play master to our slave.

Having made some previous historic site searches under primitive conditions, we knew something of the logistical needs. However, the constraints of our jobs and families limited the time available to make the trip.

We arranged for Raymond Rheborg, a pickup-owning cousin, to transport us from Fort Pierre to Mobridge very early the morning of August 3. He left us, bag and baggage, on the riverbank around 7 a.m. and we flew at the task of assembling the pre-cut pieces of the raft frame. Twenty penny spikes fastened the green cottonwood 2-by-8s and steel cable secured four sealed 30-gallon steel drum floats in frame pockets at the corners. As soon as the plywood deck was nailed down, we piled our tools, tent, large water cans, blankets, food and other gear amidships and pushed off the bank.

Exhilarated to be afloat, and with the raft well balanced and riding high, we worked our way toward the west side of the river, where the main current flowed. A long, stout pike pole was used to push off from the river bottom and, when the water was too deep for that, we managed to row clumsily with a paddle fashioned from a piece of board.

By mid-afternoon we were having trouble staying in the main channel. When we drifted out of its stronger current, our downstream progress slowed drastically, and eventually we would begin to bump and drag on the bottom in shallow water. As we struggled to keep our cumbersome craft floating in deeper and swifter water, learning to "read the river" far ahead became a priority in positioning ourselves to avoid trouble. We learned how varied shadings of light on the water's surface translated into varying depths in the river and we learned to "see" trouble ahead. As the river bends, the main channel moves from side to side and our limited ability to propel the raft laterally dictated early action and hard, hard work with our crude paddle and pike pole to stay in swift water.

Our first afternoon wore into evening. Our preoccupation with steering and navigation meant we had not been able to erect our pup tent on deck and get the rest of our gear squared away. Dusk came, then darkness, and our ponderous raft was riding a good current along the west bank of the river.

The river bank for several miles, however, was four to 10 feet in height , a sheer, vertical cut bank with nothing we could tie up to and no shore at water's edge to beach the raft securely for the night. This presented a clear danger as we could barely distinguish that high bank from the dark of the night sky and could see hardly at all ahead of us. Flashes of lightning from an oncoming storm enabled us to see, in quick glimpses, what lay ahead.

We desperately needed a safe place to moor for the night. By 10:30 the lightning and thunder foretold a major thunderstorm. Finally we were swept into shallower, slower-moving water and grounded on a sandbar. With the temperature cool for an August night and the wind freshening, we got off and pushed the heavy raft as best we could. The storm was now upon us. Bumping along on the sandy bottom, we finally ran aground in a tiny inlet amidst lightning, heavy wind and lashing hail.

In the dark and confusion our maps blew overboard and carried away. We lay, spread-eagled, on top of the rest of our equipment to keep anything else from blowing away and covered ourselves with the canvas tent. From 11 p.m. till 1 a.m. we slept fitfully, fearful we might begin to drift again.

The rain finally eased and the wind dropped. Feeling somewhat safer, but soaking wet and very cold, we "slept in" till around 4 a.m. and then got up, thoroughly uncomfortable. A driftwood fire in our tin camp stove brought warmth and hot bacon and eggs. We pushed off again.

Morning light had shown us we were in a secondary channel between a huge sandbar and the west bank of the river. At 8:15 we passed the downstream tip of the bar and merged with the main channel and faster current once again. The warming sun soon lifted our spirits. We talked with an Indian man on the west bank who told us we were but a few miles from Cheyenne Agency, which meant we were farther along than we had supposed.

About an hour later we were stopped dead in the water, hung up on a partially submerged cottonwood log — a sawyer, the legendary nemesis of steamboat pilots. It projected just above the surface at an acute angle. Because of the tremendous pressure of the current pushing us up the sloping log, the threat of having to abandon the raft and most of our equipment was very real. But rocking the raft and shifting our cargo prevailed and we finally slipped free. Such hazards and others were frequent throughout the journey, but we managed to avoid most of them by determined paddling and poling.

A curious feature of the river, still unexplained, were the "boilers," sudden upsurges of water rising from 6 to 18 inches above the surface like giant air bubbles seeking escape from the water.

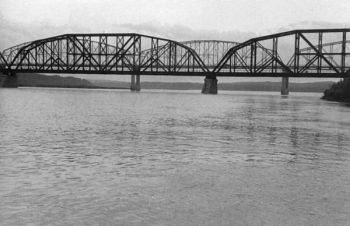

At 4:50 the second afternoon we passed beneath the old highway bridge at Whitlock Crossing. By 7:30, having had supper on board, we were moving in midstream, working our way toward shore and a hoped-for safe mooring a few miles below Cheyenne Agency. Another storm was approaching.

We landed on a sandbar at 8:30 and tied up to two large logs with the raft setting on a mud bottom. High winds and a bit of rain hit us again, but this time we were prepared. Our tent, erected on deck, kept us dry and comfortable.

The hot, burning sun of daytime hours, magnified by reflections off the river, and the strenuous physical effort needed to maintain our forward progress left us ready to sleep at night. The hard work notwithstanding, we spent much time observing the passing scenery — the land and sky, wildlife and plant life. Majestic great blue herons, magpies, hawks, buzzards and eagles were our companions, as well as the usual small prairie and shore birds. To lift the spirit, what can compare with a meadowlark's song?

Our movement on the river's surface caused little or no concern to wild animals, though we learned the sound of the warning slap of beaver tails on the water. Except for the sound of birds' and coyotes' nighttime chorus, there was no noise save the little we made. Fox, coyote, deer, antelope, beaver, muskrat and skunk were unperturbed, as were the many cattle grazing near the banks. At one point we exchanged close-up stares with a badger drinking at water's edge.

We fished daily, routinely, without any luck. Four decades ago the Missouri 's water was far from the clear blue and green of today. Instead, it was a muddy brown, said to be too thick to drink and too thin to plow. That, along with its untamed power and unpredictable ways, was about to come to an end. Oahe and the other great South Dakota dams — Big Bend, Fort Randall and Gavins Point — would permanently change its color and its unique character.

Our third morning found us drifting near the east bank, and as morning wore on, the landscape became more rugged.

August, in those pre-dam years, was a time of low water on the Missouri. While summer storms brought needed moisture to the prairie grasslands, little of it ran off into the draws, ravines and creeks that split the land. Most of the creek mouths we passed were dry.

Riverbanks often rose steeply above the summer water level. The high banks showed clearly the effects of much higher currents of spring and early summer. There were frequent trees hanging by their roots from current-eroded banks, their trunks and branches extending into the water just where the fastest current flowed. We called them "sweepers," for they could sweep our raft clean, down to its deck, unless we were alert to spot them ahead and to succeed in maneuvering around them. That was not always certain and never easy. One time, all our strength and a large measure of luck were required to free ourselves from a particularly hazardous tangle of tree branches and flotsam, in which we were held by a swift current.

Late in the afternoon of our third day we neared the entrance to the Little Bend. There a party of men and boys in two aluminum canoes passed us, heading downriver. It was a Boy Scout group from Miller. Jim Graham, one of the leaders, said they had put in at LeBeau and were headed for Pierre.

At 7:30 we moored to a heavy log on what was then the south bank of the river. Another storm was in prospect, but we were spared the worst of it. A brilliant lightning display and a brief wind squall with no rain allowed a good night's sleep.

Next morning we rose at 5:15 and were under way at 5:38, choosing to prepare breakfast on board as we drifted on through the Little Bend. Our small tin stove mounted on the stern was a great convenience. The sky was patched with clouds and a few raindrops fell as we ate. For another of countless times we went aground on a sandbar but, jumping overboard, we worked our way off with little trouble. A fresh, cool breeze gave temporary relief from the daily August heat and broiling sun.

Passing the mouth of the Cheyenne River, we spoiled a group of nine tents on a high slope along its south bank. It was headquarters for an archaeological survey party. As plans for the system of dams on the Missouri were developed, a salvage archaeology program was undertaken by the Smithsonian Institution to sample locations of historic and prehistoric significance — Indian villages and burial grounds, fur trade posts and military sites.

That afternoon a strong wind from the southeast pushed us toward the west bank, away from the deeper and swifter current. We pushed and paddled steadily for several hours to keep our raft moving downstream. Evening promised yet another storm and once again we were running along a high bank, this one of caving sand and clay, with no place to tie up. Finally, at 8:15 we moored to a sheltered log amidst light rain, continuing thunder and lightning. Nonetheless, we turned in by 9 o'clock and had a restful night.

Next morning we wasted no time, resuming the trip at 5:14. Two hours later we were caught in shallow water along a large sandbar. Standing in the water, we had to heave and tug on the raft to get through. We then clawed our way across the current to the main channel near the east bank. By mid-morning we were paddling constantly to keep from being swept into fallen trees and snags.

Early in the afternoon the flattop of Oahe Dam came into view. We were proceeding southeast on a rapid current, but a strong southeast wind countered much of our speed. At 3:10 we passed the head of Wood Island. The dam cuts across the lower portion of Wood Island, and the remainder now lies deep beneath the surface of the reservoir.

A V-shaped opening in the nearly closed dam marked our passage. Heavy earth-moving machines, dwarfed by the massive dam structure, were busy narrowing the cut with huge loads of rocks and dirt, the main flow of the river having been diverted through a temporary channel that made an end run around the west side of the dam. We passed through at 4:25, still fighting the southeast wind.

It was nearly three hours later when we floated beneath the old Highway 14 bridge connecting Pierre and Fort Pierre. As we moored our craft to two huge cottonwoods at the north edge of Fort Pierre a few minutes later, another thunderstorm was building in the west.

Those days on the river — the Old Missouri, before it was corralled and calmed by the Corps of Engineers — will never be forgotten. In those days the river simply went its way, eating up land here and spitting it out to form new land somewhere else. It served up catfish, bullhead, occasional northern pike, needle-like gar, prehistoric-looking sturgeon and other species to the relatively few who fished its turbid, snag-filled waters.

We were among the last to see it and its quiet, serene border lands before boat ramps, marinas, camping sites, resorts and bait shops came. The price of viewing it as we did was hard work in the burning August sun and nightly thunderstorms. Yet we found time to reflect on those who had gone before: Lewis and Clark, Manuel Lisa, Hugh Glass, Pierre Chouteau, Jr., George Catlin, Prince Maximilian and, before them, the Sioux, Mandans, Arikaras and Yanktons. We thought about them and the many others — fur traders, explorers, vagabonds — whose highway had been the Missouri.

Around sundown, cross-legged on deck, as we made coffee over driftwood fires and sipped it from tin cups, we were stilled by the beauties of sunset, lightning and the sparkling, star-filled night sky, each of which confirmed our role as a part of it all.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 1995 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thanks to Misters Young & Kilian for sharing the final history of the free flowing Missouri River, and may their souls rest in peace, which I'm fairly certain they do...

Question: The color photo attached to this article of the trees on the bank of the Missouri, was this photo taken in 1956? And is that Blue Blanket Island seen in the distance?

Would appreciate hearing from you, please contact me via email: hintonjb@gmail.com