The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Peace Medallion: A Work In Progress

Jul 18, 2016

|

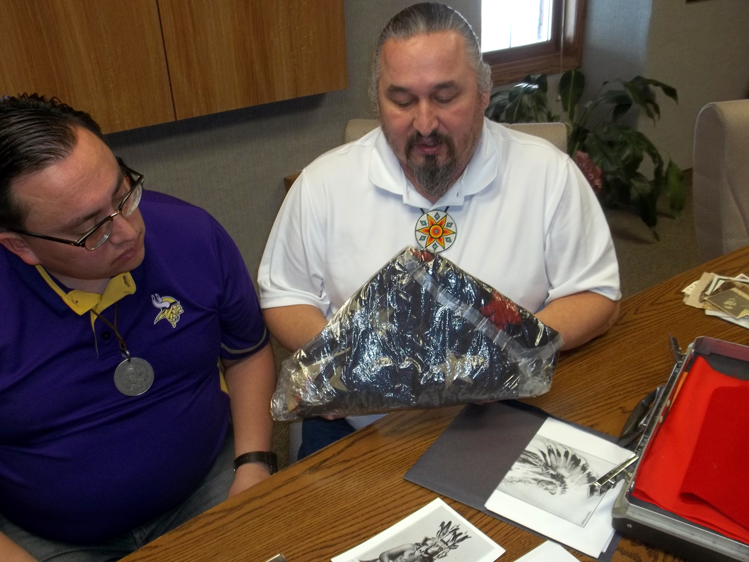

| Brothers Arik (left) and Bryan Williams possess the medal that government officials presented to their ancestors at the signing of the 1851 Treaty. |

People who live on the Coteau des Prairies in northeastern South Dakota know about Fort Sisseton, Sam Brown’s ride and the Lake Traverse Reservation, but may not be well informed about the history of our Native American population.

WESTERN EXPANSION

Several excellent history books detail the western movement of European settlers in North America, and the subsequent western push of the native population. The Heart of Everything That Is, by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin, includes a lengthy history lesson setting the table. The Sioux tribes were a part of that movement. Here in northeast South Dakota, the history lesson is really squeezed into about a 20-year period that preceded statehood by 20 years.

TREATY OF TRAVERSE des SIOUX

On July 23, 1851, near a natural ford on the Minnesota River north of St. Peter, Minnesota, the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Upper Dakota, among others, signed a treaty ceding their lands in Iowa and most of Minnesota while creating two reservations along the Minnesota River. A common practice at treaty signings was the presentation of peace medallions. The custom had begun even before the Revolutionary War to curry favor and recognize tribal leaders that aligned with the British or the French. The practice continued under the new American government as it expanded west into the lands of the Louisiana Purchase … and that’s where my lesson began.

|

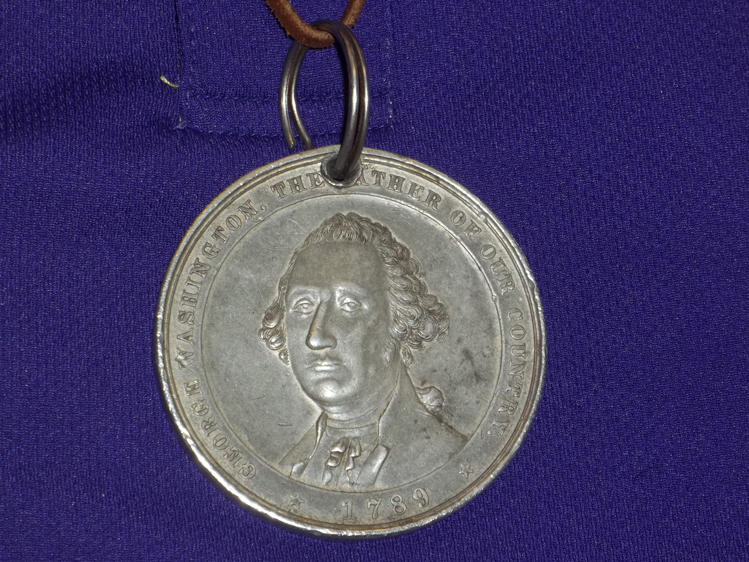

| The front of the medal includes a bust of George Washington. |

WILLIAMS FAMILY

The Williams family has roots reaching back to the days of the first Sioux to come to South Dakota. The current sons, Arik and Bryan, are descendants of Laurs Williams, Dan Williams, Moses Williams, Siyaka and Wa’anta. They have the honor of possessing a peace medallion from the 1851 Treaty signing, and the flag that flew over the event that day.

The peace medallion is solid silver, and has a hole near the top so that it can be worn (old photos often show chiefs wearing the medallions awarded to them). This medallion has a bust of George Washington engraved on the front and an inscription that reads, “George Washington, The Father of Our Country.” The reverse shows two hands shaking, the year 1789 (the year the United States began operation under the Constitution), and “The Pipe of Peace” and “Friendship.”

The flag has 30 stars, consistent with the American flag in production from 1848 to 1851. It is in tender condition and hasn’t been unfurled in many years.

|

| The Williams brothers also protect the American flag that flew over the treaty negotiations. |

DAKOTA WAR OF 1862

When people are moved to war, rarely would one event explain the cause – the world is more complicated than that. But in 1862 war did break out in the Minnesota River Valley. At least some of the blame is laid upon the Trader’s Paper, a document signed with the 1851 treaty. It gave priority to payment of Native IOUs to traders, from the Native’s government treaty payments before funds and benefits provided under the treaty were paid to the dependent local Native population. The leader of the Mdewakanton band, Little Crow, began attacking white settlers, and by the end casualties from both sides totaled more than 1,000. The Dakota War is chronicled in detail in Scott Berg’s 38 Nooses. The book derives its title from the mass hanging of 38 Sioux warriors in Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862. The actual number convicted and sentenced to death was 303, after 392 trials spread over 30 court days. Ultimately, President Lincoln pardoned all but 38 of the death sentences. The remaining Sioux in Minnesota were eventually relocated to the present Crow Creek Reservation in central South Dakota as punishment for the uprising, but the real motive was largely to clear western Minnesota for non-Native farmers and settlers.

SIOUX TREATY OF 1867

The boundaries of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate today were established in 1867. The Sisseton and Wahpeton bands had not participated in Little Crow’s war, and had rebuffed his attempts to engage them in the conflict. In recognition for that, the Sisseton and Wahpeton were not relocated west, and the current boundaries are reflected in the 1867 treaty. South Dakotans readily recognize the triangle shaped reservation stretching from Lake Kampeska across the Coteau Hills to just across the North Dakota border. The treaty document even refers to currently recognizable “Kampeska Lake” and the “Coteau des Prairie(s).”

|

| The Grand Entrance signifies the opening of the annual Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Pow wow. |

FORT SISSETON AND SAM BROWN’S RIDE

Historically, Fort Sisseton and Sam Brown’s ride happened after the Dakota Wars, but before the peace treaty. Fort Sisseton was built in 1864, two years after the war, but while memories were fresh and tensions still existed. Sam Brown’s ride came in this same time period. Sam Brown, of present-day Browns Valley, rode in the winter to Fort Sisseton to warn of an Indian uprising. Upon reaching the Fort and learning that the news was in error, he rode back into the blizzard to warn locals and avert possible bloodshed. Brown lost his legs to frostbite, and is locally referred to as the Paul Revere of the Midwest.

The Fort was located, ostensibly, to protect the Native population from intruding white settlers. Today the Fort has been restored and its role on the frontier is celebrated each year on the first full weekend in June by thousands of visitors. A month later, over Fourth of July weekend, the Sisseton Wahpeton celebrate their annual pow wow, which is open to all.

LITTLE BIGHORN

The 1876 battle in Montana, commonly referred to as Custer’s Last Stand, might seem far removed from the Coteau of northeast South Dakota, but the lingering tensions Sam Brown recognized existed on both sides of the racial divide. Descendants of Wa’anta report that their family fought with Sitting Bull in Montana that June day 140 years ago. Robert Utley’s Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot confirms that Sitting Bull’s encampment included 15 lodges of Dakotas who were defiant over their treatment after Little Crow’s defeat.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

The Williams sons take their tribal legacy seriously. The unfilled treaty promises are recounted in the same breath as their family’s military service to America. Their family fought with the United States in the Civil War as a part of the Minnesota Regiment, both World Wars, Korea and Vietnam. Two of their siblings served in Desert Storm. It’s estimated that 400 descendants of Wa’anta have served in the United States military.

What seems like a long time ago, Gov. George S. Mickelson proposed a Year of Reconciliation. Undoubtedly, Natives and non-Natives interact more and better each year as the invisible boundaries that separate the two cultures dissipate. We’ve elected a Lakota U.S. Congressman, Ben Reifel. I’ve served with Sen. Jim Emery, a tribal member elected to represent a non-reservation district. Circuit Court Judge Tony Portra is of Native descent. It’s all progress, but there’s probably a reason they made those peace medallions so durable – they have to hang around a long time and they still have a lot of work to do.

Lee Schoenbeck grew up in Webster, practices law in Watertown, and is a freelance writer for the South Dakota Magazine website.

Comments

Of course, the South Dakota Democratic Party should urge President Obama to dissolve the Black Hills National Forest, move management of the land from the US Department of Agriculture into the Department of Interior; and, in cooperation with Bureau of Indian Affairs Division of Forestry and Wildfire Management, rename it Okawita Paha National Monument eventually becoming part of the Greater Missouri Basin National Wildlife Refuge. Mato Paha (Bear Butte), the associated national grasslands and the Sioux Ranger District of the Custer/Gallatin National Forest should be included in the move.

Mr. Shoenbeck meant to write about SAM Brown's ride. Brown was crippled for the remainder of his life from his efforts that day to warn settlers and then double back to let them know it was a false alarm.

The town of Browns Valley recently celebrated their 150th with tours of Sam Brown's cabin, Native American Dancing, parades and an altogether great event.