The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

USD’s Anarchist Professor

The football game was tight that October night a hundred years ago, emotions high. The University of South Dakota was on the rival’s grid, her fans outnumbered by partisans of the home team. Agitated youths from Mitchell went too far when they tore the USD colors from the hands of a cheering USD co-ed. The girl’s friends struggled to reclaim the banner, but in the skirmish that ensued, outnumbered USD students were being soundly trounced.

Professor Alexander Pell to the rescue. The usually mellow professor of math leapt into the fray, decking attackers one by one. When the brouhaha was done, according to a story in the 1902 student newspaper, the Volante, Pell emerged with bloodied face and torn shirt, but with highest esteem from his students.

Pell had earned a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1897, and that fall, the 40-year-old and his wife, Emma, arrived in Vermillion. He had been hired to teach math at the fledgling university on the prairie at the north edge of town.

Pell’s Vermillion friends knew that he was born in Russia, that he had fled the czarist rule of his homeland, first to Canada and then to the United States. They knew in a general way that Pell had opposed the czar. But they knew few details about his life before he arrived in America. Pell talked little about his past.

Pell quickly gravitated to the center of social life in Vermillion, playing in chess tournaments, ice skating, entertaining the football team in his home, leading pep rallies as well as academic debates, taking his turn directing chapel exercises.

Alexander and Emma Pell even took needy students into their home.

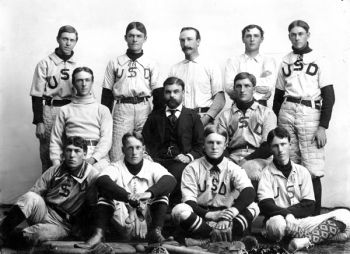

In those early days, USD counted 410 students. Pell realized there might never be enough students to fill his math classes, so he shifted to applied sciences and promoted the idea of a department of engineering, a goal he would reach in 1903. Pell was regarded as “a model teacher, an able administrator, and a kind, generous, outgoing friend to students and faculty colleagues,” wrote Von Hardesty and John D. Unruh, Jr. in a 1972 article in South Dakota History. In 1904, the year Emma died, students dedicated the Coyote yearbook to the Pells.

Pell’s popularity and his proselytizing grew the new engineering department so rapidly that within two years, the governor was complaining that there was “too much mechanical engineering [taught] at Vermillion.” By 1907 the engineering department was firmly established, with Pell as its dean. Pell’s friend, the legendary Dean Lewis Akeley, would later recall that Pell had once proclaimed that girls couldn’t make it as mathematicians, and if one did, “someone would marry her and spoil it all.” Nevertheless, in 1907, when he was twice her age, Pell married his prize former student, Anna Johnson from Akron, Iowa, whom he had tutored and promoted for graduate study.

It came as a surprise the next year when Pell resigned his full professorship — and the $1,650 salary that went with it. He and Anna moved to Chicago, where Alexander taught math and theoretical mechanics at Armour Institute of Technology, and where Anna earned her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, the second USD graduate to earn a terminal degree.

In 1911 Pell suffered a stroke, which two years later forced him to give up teaching. Anna was appointed assistant professor of math at Mount Holyoke, and the Pells moved to Massachusetts. Later they moved to Pennsylvania, where Anna taught at Bryn Mawr. There, in 1921, Pell died, and with him, Sergei Degaev.

Perhaps if Alexander Pell’s students at USD had known of their professor’s former life as Sergei Degaev, they might have better understood his rampage on the football field. If they had known that a “wanted” poster issued by the czar’s imperial police two decades earlier had offered 10,000 rubles for his capture, they would have been impressed. If they had known he had betrayed his comrades and shot a secret police officer in cold blood, they might have feared him.

But that was not Alexander Pell. That was Sergei Degaev. That was a different continent, a different time, far from the insulated life of Vermillion, where adoring students called him “Papa Pell.”

Sergei Degaev was born in 1857 into a Russian family fermenting with revolutionary fever. The lad grew up dreaming of derring-do to free his country from tyranny, a place where merely criticizing the czar could send one to prison for years of hard labor. At the university he studied mathematics, engineering and languages, but was attracted by anarchist politics. Nevertheless, upon graduation he was commissioned a sublieutenant in the Russian army, retiring three years later as a captain.

At some point, Degaev joined a radical group known as the Peoples’ Will, whose goal was to assassinate Czar Alexander II and establish a revolutionary government. Among the projects in which Degaev engaged was tunneling from a cheese factory under a road traveled by the czar in hopes of blowing him up when he passed. That plot failed, but in 1881 another succeeded, and the czar was dead. To the dismay of his enemies, Alexander II was replaced by his son, the even more repressive Alexander III.

In 1882 young Degaev was caught with an illegal printing press and sent to prison. In prison he came into contact with Col. George Sudeikin, inspector of the Russian secret police. It is unclear how the deal evolved, or exactly what it entailed, but perhaps Sudeikin convinced the prisoner that the hope of changing Russia depended upon cooperation between reformist elements of the secret police and the revolutionaries. Apparently an agreement was reached in which Degaev’s escape from prison would be arranged, so he could continue attacks on Sudeikin’s corrupt rivals. In return, Degaev identified comrades who might be drawn into the proposed collaboration.

When the friends he named were arrested, Degaev realized he had been had. He confessed his part to the leader of Peoples’ Will, and was ordered to atone for his sin by executing Sudeikin. Now living under the pseudonym Pavel A. Jablonskii, Degaev used the confidence he had built with his police conspirator to lure him to his apartment. He shot Sudeikin in the back. Two accomplices finished him off with crowbars.

But Dagaev was still distrusted by former comrades, who would soon expel him from Peoples’ Will as a police collaborator. Meanwhile, he was hunted by the police for the assassination, a 10,000-ruble price on his head. Dagaev’s wife, Emma, had fled to Paris, and in 1884 he managed to escape Russia and join her. From there they sailed to Canada, where he faded into obscurity, working as a stevedore and in a printing shop.

In 1886 the Degaevs turned up in St. Louis, he under his third name, Alexander Pell. He got a job as superintendent of a chemical plant, became a naturalized citizen in 1891, and began studying math. In 1895 he entered graduate study at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, receiving his doctorate with honors in 1897. That fall the Pells arrived in Vermillion, where his latest life began.

Though Alexander Pell risked discovery by returning occasionally to the East Coast and even to Europe, he did take steps to cover his trail. The year after Pell left Vermillion, he and his brother arranged to have widely published the obituary of Sergei Degaev, purported to have died in New Zealand. Nevertheless, a former fellow anarchist living in New York discovered his old comrade’s new identity in 1915. Apparently respecting Degaev’s good works in later life, he decided not to expose him as a traitor, leaving him to live in peace. In the words of Von Hardesty and Unruh, Sergei Degaev, “informer, agent provocateur, killer” had become Alexander Pell, “outstanding scholar, beloved teacher, warm friend and counselor to students, loving husband.” And defender of cheerleaders, extraordinaire!

Editor’s Note: The author, Dana Jennings, was a longtime South Dakota journalist who passed away in 2009. This story is revised from the May/June 2004 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments