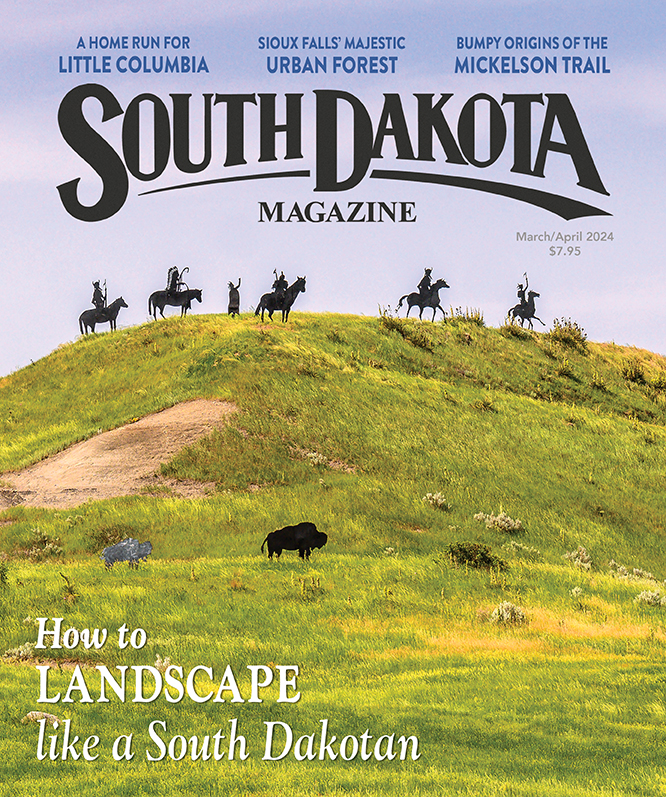

The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

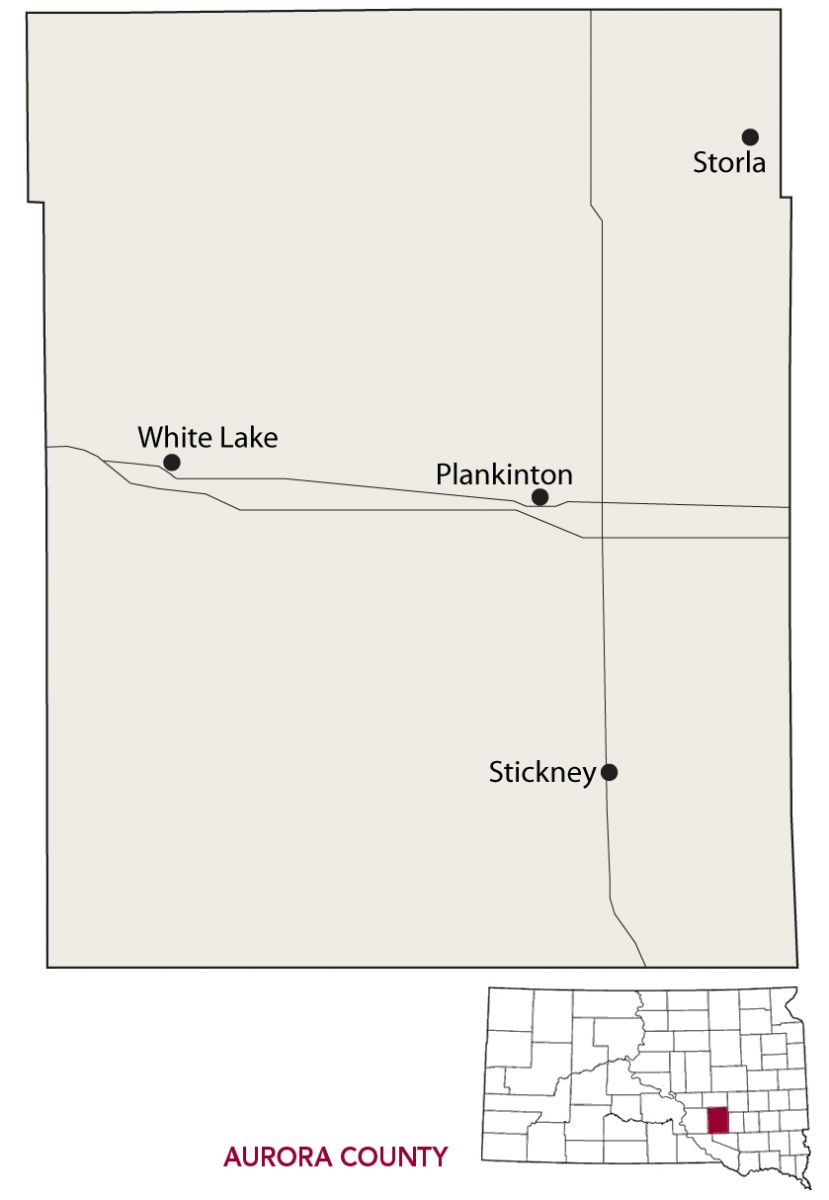

New Days in Aurora County

May 3, 2016

|

The people of Aurora County are no strangers to trials and tribulations. They’ve seen droughts, tragic deaths and failed enterprises since the county’s creation in 1879. But there have been, and continue to be, bright spots. If there’s ever any doubt, citizens need to look no further than the very name of their homeland for inspiration.

Aurora County is named for the Roman goddess of the dawn. In mythology, Aurora is renewed each morning and flies across the sky, announcing the coming of the sun and the birth of a new day, a new beginning. In the realm of South Dakota county nomenclature, Aurora certainly stands out as unusual. Of our 66 counties, 43 were named after legislators, governors or other prominent men involved in the creation of Dakota Territory. Another 11 were named for famous national politicians or military leaders. So why would the territorial legislature turn to a female mythological figure when naming this new county?

It turns out they didn’t, because legislators didn’t name it. Aurora came from a group of women gathered in a sod hut, probably one of the first homes in the area. Ruth Page Jones, an Aurora County native and independent historian living in Wisconsin, mentioned the story at the Dakota Conference, held in late April at Augustana University in Sioux Falls. Jones is studying the early settlement of her home county and is seeking more information about who the women were and where the hut was located.

In 1880, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad arrived in Aurora County, prompting the establishment of Plankinton and White Lake. Shortly thereafter, a grand hotel was built in Plankinton to accommodate travelers. The building still stands and is nearing restoration as a wedding chapel, cultural and arts center and railroad museum.

|

| Volunteers have spent over a decade restoring the Sweep-VanDyke Hotel in Plankinton. |

The Sweep-VanDyke Hotel is one of two still standing in South Dakota along the old Chicago and Milwaukee line. As the only hotel for miles, travel-weary passengers viewed the charming two-story structure with its welcoming veranda as an oasis on the prairie, says Gayle Van Genderen, president of the Plankinton Preservation Society and publisher of the South Dakota Mail, Plankinton’s weekly newspaper. “Early accounts say people would push each other over just to get a night’s sleep on one of its feathered pillows,” she says.

The hotel is named for George and Ella Sweep, proprietors in the early 1900s, and Bert and Barbara Van Dyke, who ran it as a boarding house before it closed in the early 1970s. It was slated for demolition, but the preservation society bought it in 2004. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. A dedication is set for July 23.

|

| Plankinton's signature purple water tower stands along Main Street. |

The citizens of Plankinton had a knack for grand buildings. Grain palaces in which to house agricultural expositions were all the rage as the town was getting on its feet. From the 1880s to the 1930s, at least 34 grain palaces were built in at least 24 towns around the Midwest, according to Rod Evans’ book Palaces on the Prairie.

Plankinton opened South Dakota’s first such palace in September of 1891. The building was about 80 feet square and stood at the north end of Main Street, but the Aberdeen Weekly News still believed it would be “the greatest display of grain ever shown by any country.” It drew a mighty crowd for its festival, including a band from Lennox and trainloads of spectators from Sioux City and Mitchell.

The next year Mitchell decided to build a grain palace of its own, and the friendly competition between the neighboring cities induced the people of Plankinton to build an even larger palace for the 1892 celebration. But in 1893 the people decided their town couldn’t support a third palace, partially due to the success that Mitchell saw the previous year. The Plankinton palace was torn down and rebuilt as a barn outside of town. Today a painted sign that advertises the 1892 exposition is among the only items to have survived. It hangs in the Aurora County Historical Society’s museum, while the Mitchell Corn Palace has become a world famous tourist destination.

About 10 miles west along the railroad tracks (eventually supplanted by old Highway 16, a popular east-west route across South Dakota) stands White Lake, a town named after the nearby body of water. The first recorded exploration of the area came from the noted artist George Catlin in 1832. Catlin was aboard the steamship Yellowstone, which was making the first ever trip along the entire length of the Missouri River from St. Louis to its headwaters. Perhaps the boat made a regular stop or ran aground on a sandbar, but whatever the reason Catlin departed and walked overland to Fort Pierre, passing White Lake along the way. While in Fort Pierre, Catlin completed several of the Native American and prairie scenes for which he became known.

|

| Bob and Edith Zoon operate the A-Bar-Z Motel in White Lake. |

The world’s attention once again turned to White Lake in 1935, when the lighter-than-air balloon Explorer II touched down. The flight had launched in frigid weather from the Stratobowl near Rapid City on Nov. 11, 1935. Explorer II reached a height of 72,395 feet, an altitude record that stood for 21 years. The aeronauts on board collected new information about high-altitude atmospheric conditions. They also provided the first photographs to show the curvature of the earth against the backdrop of space. Explorer II drifted 230 miles east, making a successful soft landing in a pasture about 12 miles south of White Lake. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the landing in 1985, local volunteers led by Howard Herrick constructed a 5-foot-tall marker made of fieldstone. You can find it on 265th Street near Platte Creek.

|

| A stone marker stands south of White Lake where Explorer II landed in 1935. |

Stickney is the third town in Aurora County. While not on the old railroad, or Highway 16 or Interstate 90, it is on Highway 281, a major north-south route through the state. Stickney was founded in 1905 and named for the family that founded Stickney in Great Britain. A descendant of that family visited for the town’s Fourth of July celebration in 1906. Stop at the 281 Diner for a burger and ice cream cone.

There has been sadness in Aurora County. In 1887 Cephas Ainsworth became superintendent of the Dakota Reform School. Ten years later, the school endured tragedy when a fire broke out in a locked dormitory and killed six girls. They lie in a mass grave marked by white chains in the town cemetery. A century later, 14-year-old Gina Score died after running 2.7 miles on a hot and muggy day. Today the State Training School is closed, but the facilities are used as a residential treatment center for youth called Aurora Plains Academy, invoking the namesake of the county that reminds us that a new day — and a fresh beginning — is right around the corner.

Editor’s Note: This is the 23rd installment in an ongoing series featuring South Dakota’s 66 counties. Click here for previous articles.

Comments