The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Dancing in the Sacred Hoop

|

| Kevin Locke plays a courtship melody he learned from Lakota elders on a traditional cedar wood Lakota flute. |

He enters the powwow circle, and like a magnet draws all eyes. He is vigor and smile, a muscular man in long black braids. He wears an aqua ribbon shirt, beaded moccasins, a breechcloth over shorts. A duffel bag balances on his shoulder. He strides to the center and slides his load to the floor as the master of ceremonies announces his name: "Ladies and gentlemen: Kevin Locke."

The audience stands and claps as Locke opens his bag. He extracts a traditional Lakota cedar wood flute from its leather wrap and begins to play. The song is a heart-opening courtship melody that Locke inherited from generations of elders, an intricate piece that softens the heart, mellows the spirit.

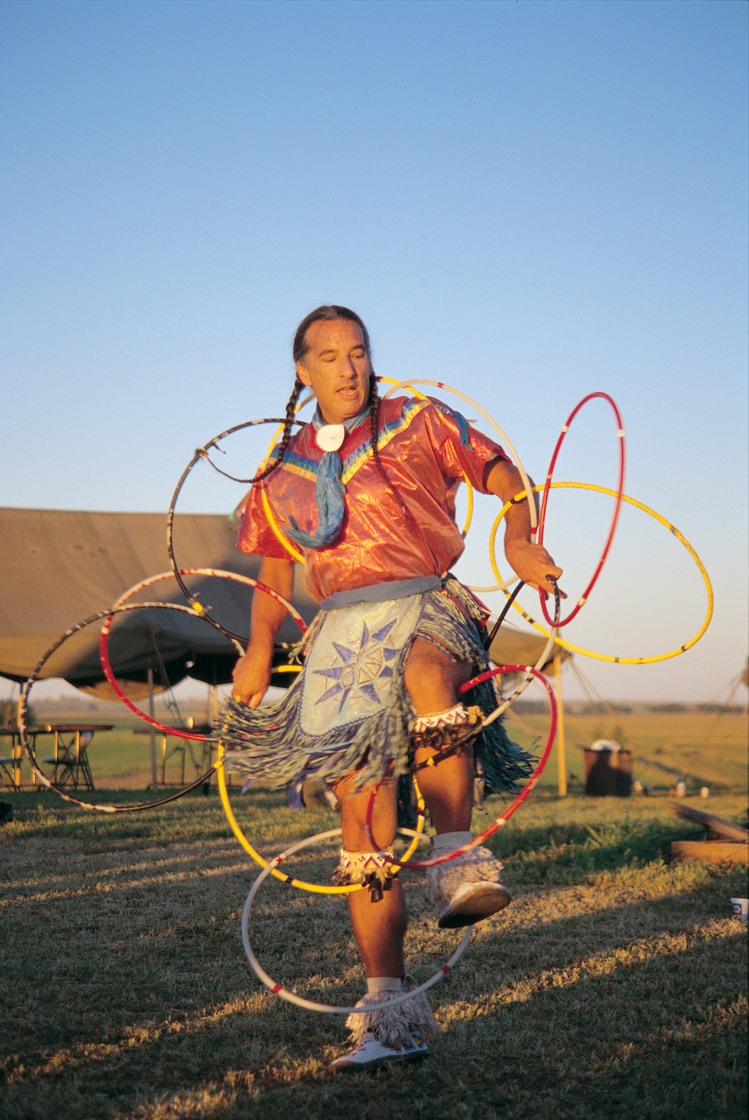

The tune comes to its end and tenderly he lays the flute aside. From the duffel bag he withdraws a big handful of four-colored hoops — red, white, yellow and black. He arranges the hoops on the floor before him. Four men around a big hide-topped drum begin to play. Locke picks up the beat of the drum, and the dance begins.

If the wistful notes of the flute had calmed the soul, the blood is riled to boiling by the dance to come. A whirling dervish, the veritable soul of a whirlwind, Locke scoops up the hoops, one by one, with his toe. They spin about his ankles, rise to his knees, then to his hips to meet his hands. Clockwise he spins, but in the blink of an eye his motion reverses. Around and around he whirls to the beat of the drum, the throbbing nucleus of the circle of humanity of which he has assumed the center.

|

| The figures Locke creates in his dances are constructed of red, white, black and yellow hoops, symbolizing the interrelatedness of the human races. |

Above his shoulders a delicate flower blooms from the hoops, only to metamorphose into a fluttering butterfly, then stars and moon and sun. As the dance goes on an eagle extends its wings, madly spiraling, calling forth the love, courage and intelligence of our hearts.

Long having passed the normal bounds of human endurance, the final movement of Locke's dance at last begins. In this final symphony, a fabulous interlinked structure defines itself, the flower, the butterfly, the eagle and the heavenly bodies evolve to an orbiting globe of human diversity — 28 interlocked hoops, a picture of the unity of humankind.

The dance at its end, Locke bows low and thanks the audience for its thunderous applause. Carefully he extracts his body from the structure he has built and presents it to his audience on the floor. Though he is wet with sweat, his incredible stamina and athleticism belie his 46 years and his 20 years on the road. Hardly winded by the 20-minute, non-stop performance, he projects the words that his dance has spun.

The four-colored hoops represent completeness and unity, he says, the four human races, four directions, four seasons, four winds. "God wants us to reach," he explains, "reach for more light, feed our roots and blossom. We are all branches of the great human family tree. We can soar like the eagles, give off fragrance like the flowers." But we can realize our beauty and our potential only as we set aside our divisions, our distrust, our prejudice and fear of one another, he says.

His homily ended, Locke drags another 70 hoops from his bag and spins them across the floor to the people who form the circle. They step forward to embrace the hoops — Indian girls in jingle dresses, grandmothers in shawls, men in feathers and beads, others in jeans or suits — and the enchanted assembly joins the dance.

When that dance is done Locke gathers the hoops again, thanks the dancers and drummers, and offers thanks to God/Wakan for holding us in the palm of his hand as we walk with strength this beautiful road of life.

This is Locke's second of three performances this day — the work around which his life has revolved for two decades. His performances have helped to revive the traditional Native flute, and he is among its top players in the nation, with 11 recorded albums of his music. And he is perhaps the premier living hoop dancer, having performed in 70 countries around the world.

Firmly rooted in Lakota culture, Kevin Locke has become a missionary for human harmony and global unity. Though South Dakotan by birth and by choice, he is also a cosmopolitan citizen of the world. But Locke didn't plan to spend his life dancing around the globe. In fact, his formative years were passed in close communion with an elderly traditional uncle, Abraham End of Horn, who spoke Lakota and trained the boy in the traditions of his culture.

Locke grew up near Wakpala on the Standing Rock Reservation. When he left home in the early 1970s, it was to pursue a somewhat standard professional career. By the end of the decade he had completed the course work for a doctor's degree in education at the University of South Dakota and was planning to study law. But then his calling came.

|

| Locke projects an image of human harmony with this whirling chain of interlocked hoops. |

A North Dakota brother, Arlo Good Bear, offered to teach Locke the hoop dance. Kevin would travel many places, meet many people, be an emissary from the Lakota people, his friend told him. Good Bear offered one lesson now, and promised more in the future. The two got together and Good Bear introduced Locke to the dance of the sacred hoop. A week later, Good Bear was dead. Locke was among the men who carried him to his grave.

Back to the traditional career in education or law, Locke thought. But then the dreams began. Not once, not twice, but again and again, he met his friend in his dreams. And there were others too, people from across the generations, people from around the globe, from many other tribes, Europeans, Asians, Africans. In the dream, Good Bear danced designs of nature, birds, flowers and rainbows. Locke saw that his brother had kept his promise. The lessons were continuing, and with them, a clearer definition of Kevin's role. He saw that he must carry this thing forward, create patterns of beauty that would unite peoples around the Earth.

As his dreams foretold, Locke has traveled and lived among the tribes and peoples of the world. His heart has sponged the spiritual visions of all, his mind their wisdom. He has studied the spiritual quests of man, and conclusions have grown: At bottom, and properly interpreted, the great spiritual visions of humankind are the same. They lift our spirits, give us hope, unite our dreams, extend our arms around each other. This unifying vision Locke has found best expressed in the words of the 19th century prophet Bahá'u'lláh.

Locke grew up under the influence of both Christian and Lakota spiritual traditions. But his personal vision coalesced when he found the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh, a Persian nobleman in Iran who in the middle of the 19th century gave up the comfort and security of his princely life to seek and teach a vision of global unity of humankind. Bahá'u'lláh taught that there is only one God and only one human race, and that all religions have been stages in the revelation of God's will and purpose for humanity. "The earth is but one community," he wrote, "and mankind its citizens."

For Locke, the Bahá'i Faith is a logical extension of the teachings of Lakota culture. The family and tribal unity symbolized by the sacred hoop of the Lakota is broadened to include the entire family of man. Bahá'i incorporates the missions of transcendent visionaries such as Krishna, Moses, Buddha, Jesus and Muhammad, finding unity instead of conflict in these separate visions. Now humanity has come of age, endowed with the collective capacity to see the entire human spiritual panorama as a single evolutionary process. It is that which calls Kevin Locke to be a global wanderer, an international envoy for peace, a prophet of unity.

|

| Locke helps Lakota youth learn traditional songs and dances every summer at Milk's Camp, a retreat on land that once belonged to Chief Milk in Gregory County. |

Thus Locke has embraced the challenge of the new millennium we have now begun. "We must create a circle of humanity," he says. "We must move out of our 'boxist' mentality, our tendency to categorize each other. In a hoop or a circle," he notes, "there is no back row. Everybody has a front row. We must work to strengthen ourselves, links in a mighty circling chain, to overcome violence, addictions, racism and hate. " More than the world's most renowned hoop dancer, more than a leading reviver of the classical Native flute, Locke is intermediary for unity to the world, Lakota ambassador, proclaimer of peace to humankind.

"Global unity is inevitable," he says. "Peace is inevitable. It's a rendezvous that we have, and there's no getting around it. But at the same time, potent forces of disintegration and chaos confront us. Our challenge is to connect ourselves with each other and with the powerful forces of cohesion in the world. The Bahá'i community is committed to random acts of kindness, to senseless acts of beauty," Locke said. "But it's systematic, a way of life."

While Locke labors for unity and peace on the global front, he has not forgotten his native state. "I've seen a lot of progress toward racial reconciliation in South Dakota," he said. "Of course it's frustrating sometimes. I'd like to see things move faster. But there is movement, toward sobriety, toward recognition of spiritual unity, toward validation of our unique individual contributions. Today is part of a process, and hopefully we can measure progress as we move systematically down the path to reconciliation, from darkness to light."

Watching Locke dance, absorbing the sweet melodies of his flute, listening to his uplifting words, it is hard to imagine pain behind his smile. Yet, like everyone else, Locke encounters negativity and conflict. "But I try to be non-confrontational," he says. "I seek a positive avenue or attitude, and negative things evaporate and disappear."

Watching the power and elasticity with which he dances, it is also hard to imagine that he will ever stop. Yet, at age 46 he knows he can't maintain this pace and speed forever. "I plan to continue this particular spiritual mission as long as I feel I can make a contribution," he said. "Or until I see a different path for myself."

Kevin Locke gathers the last of his things, brushes back the strands of graying long black hair that have worked their way loose from his gyrating braids, and offers his hand. He is off to his third performance of the day, for a group of children at the middle school. Probably they've seen him already, on public television's "3-2-1 Contact." But they are about to encounter in person a man they will not soon forget. A man whose vision for their future could alter their lives.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2000 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments