The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Gateway to the Sandhills

|

| "Soap weed is what keeps the Sandhills from blowing away," says Jim Buckles, a third generation rancher. The spiny plant, also known as yucca, sometimes shoots a pod of seeds that cattle love to eat. |

Nebraska has bragging rights to the Sandhills, and so it should. They cover a quarter of the Cornhusker State. But the Sandhills actually begin north of the Nebraska border with an oasis of cactus, hills and water in southwestern South Dakota. And as is often true with beginnings, the South Dakota Sandhills have a story of their own.

Maps of the Sandhills show them spilling into South Dakota, but you won’t need a map to find them. Just take Highway 73 south of Martin. You’ll pass by farms and fields, perhaps wondering if you’ve yet reached the beginning. You’ll know when you do. The switch from what locals call “the hardland” to the Sandhills is literally a line in the sand. They can’t be missed.

“There’s nothing like it in the United States, except maybe very locally along barrier islands, a few hundred yards off the East Coast, and in southern California,” says Dr. Perry Rahn. “Certainly nothing to the extent that you find in Bennett County and on into Nebraska.”

Rahn, a retired professor from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City, says the history of the Sandhills dates back 2 million years to the Pleistocene, or Ice Age. “The glacier never got to Bennett County and western Nebraska, but the wind from that era might have blown away the topsoil and exposed the sand.”

Though the Sandhills have been intensely studied over the past century, scientists remain uncertain of their origins. As the glaciers melted about 11,000 years ago, the dunes took shape. Some call them a “desert in disguise” because the geology is much like dunes found in hotter climates. However, thanks to an average rainfall of 15 inches a year, a thin cover of vegetation makes them look more like Ireland than Africa.

That hasn’t always been the case, according to Rahn. He says there have been drought cycles in the past 10,000 years when the vegetation probably all but disappeared and the dunes actively shifted with massive sandstorms.

In modern times, the Sandhills have been stable. But their fragility has never been a secret. The U.S. Congress, recognizing the region’s arid qualities, passed the Kinkaid Act in 1904 to allow homesteaders 640 acres rather than the customary 160.

Retired rancher Jim Buckles, who now lives just north of the Sandhills, says his grandfather came from Oklahoma to become a Kinkaider, as the homesteaders were called. He’s lived and farmed in and out of the Sandhills, and says there’s a big difference.

“There’s a line just like that table’s edge,” Buckles says. “And when you hit the Sandhills the water is soft water and out here it is hard water.” Buckles says water is more plentiful in the Sandhills, where wells are often only 50 feet deep. “I just dug one for our house that’s 400 feet deep.”

Buckles says Lake Creek runs west to east along the very northern rim of the Sandhills in South Dakota. Largely spring-fed, the creek eventually flows into a series of man-made reservoirs that were begun in the 1930s as the Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge. Locals pronounce it Lay-creek as a reference to Lake Creek.

|

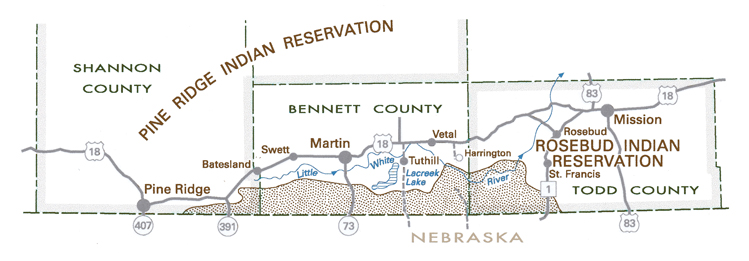

| The northern edge of Nebraska's famous Sandhills formation spills over into southern South Dakota. |

The refuge has developed into an oasis for hundreds of bird species. American white pelicans nest in large colonies. Trumpeter swans winter there from September to March. Grassland birds, burrowing owls and waterfowl can also be found, many year-round and others as a migratory resting place.

Few roads were ever built in the South Dakota Sandhills, and there is little obvious evidence of settlement other than fences, windmills and a few small cemeteries. One exception is the Ted Turner ranching enterprise. The billionaire media mogul turned buffalo rancher owns 37,365 acres in Bennett County, most of it in the Sandhills. Turner is the largest property tax payer, according to County Treasurer Jolene Donovan. He will owe $94,521.92 this year.

But Turner’s spread represents only about one-tenth of the South Dakota Sandhills, which run 80 miles east and west and extend from a few miles to 12 miles north of the Nebraska state line. Altogether, South Dakota’s Sandhills encompass about 360,000 acres, and most of it is pasture for local ranchers.

“This is really neat country,” says John Markus, who runs cattle on the demarcation line with his wife, Cathy. “The hills around here act like a sponge when it rains. This is not a desert. Water is a part of what makes it so special.”

Markus, who also keeps cattle on the hardlands, says the Sandhills are “harder to manage but worth the trouble. You don’t want to overstock these hills, but there’s a lot of the grasses, the big blue stem and some others, that are good quality for grazing and the cattle will do real good.”

He said even the yucca, a bush of yellow-green spikes that dominates much of the Sandhills landscape, is a benefit. The plant is known locally as soapweed, probably because the root was used by pioneers to make soap. “Cows are a herd animal and they are great mothers,” said Markus. “But I’ve seen good cows leave the herd, and leave their calves, and race all-out when they spy the seeds from a soapweed. They love them, and it must be really high protein, because they will really shine up on them.”

The Markuses are third-generation Sandhills ranchers. Cathy’s grandfather Carl Micheel built a ranch in Lake Creek Valley in the 1940s. His sons, bachelor brothers Melvin and Leon, ran the place for decades.

Melvin’s dream came true when Cathy and her husband decided to move there from their ranch near Mission, becoming the fourth generation.

|

| Lake Creek begins on the old Micheel ranch and eventually flows into a series of ponds that form the Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge. |

Like many Sandhills ranches, a long dirt path connects the headquarters to the nearest paved road. The house, old barns and corrals are strategically situated in a flat valley at the foot of a big hill that provides protection from the north wind. Lake Creek cuts right through the farmyard, and a grassy wetland lies to the south of the buildings.

“We mow that grass for hay,” says Cathy. “You might be able to drive along one spot just fine, and then a week later it’ll be too soft and spongy in that same spot to carry a small tractor.”

She gave us a tour of the hills and valley, bouncing along dirt roads and up and down the soft hills in a big white pickup. Springs can be found at several locations, filling small basins. At some points, the creek disappears underground. Burrowing owls spook from holes in the surrounding hillsides. Geese swim on wetlands. An 8-foot waterfall seems out of place among the yucca and cactus. The noise of spilling water is as delightful here as in the Black Hills, 100 miles to the west, but this Sandhills waterfall appears to have been plucked from the forest and planted on the prairie.

Rahn, the former SDSMT professor, says the arid Sandhills, ironically, are linked through eons of time with the massive Ogallala Aquifer that also begins in South Dakota, just beneath the dunes. That’s not a coincidence. “The source of the sand for the Sandhills is the underlying Ogallala formation,” he says. “The aquifer is 5 million years old, and the sand dunes are much more recent.”

The Ogallala Aquifer begins in Bennett County and extends to Texas, providing water for 27 percent of the irrigated land in the United States. Although it holds 3 billion acre-feet of water, it has been declining at the rate of 325 billion gallons per year for decades because of over-use in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas.

The aquifer’s depth has been holding steady in South Dakota and northern Nebraska because the sand dunes collect rainwater and snowmelt that would drain away to major rivers, like the Platte or the Missouri, under normal circumstances. Shifting sand through the centuries has clogged the creeks, allowing the water to sift into the big Ogallala.

The aquifer also remains deep and clean in the northern region because there is less of a need for irrigation. The land is mostly too rugged to farm. This is country for cows, horses and buffalo.

The Micheels and other Sandhills pioneer families were tough and colorful, according to Joyce Wilson, who runs the Martin pharmacy with her husband, Kirk, and also helps maintain the Martin museum. Old photographs and stories illustrate that nature has not only shaped the Sandhills, but the people who have lived in them.

Wilson’s grandfather, Alex Livermont, raised Clydesdales and Belgian horses in the Sandhills a hundred years ago. He also participated in massive roundups when the hills were unfenced and considered open range. Cattle could be herded, but the Livermonts once tried to trail 100 hogs to Cody, Neb., by leading them with a wagon of corn. The hogs followed along until they reached a creek or river, but then they quickly scampered for mud.

The Hillman family held dances and fish fries at their ranch near Lacreek Valley. Sometimes, the men and boys would fish for trout in a dam. On one occasion, a 3-year-old named Delbert Rolfe could not be found. Thinking he may have entered the water, the men cut a hole in the dam and drained it in their haste to find the boy. Fortunately, he was not in the water; they found him hours later in a sand blowout, sleeping.

|

| The Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge covers 16,410 acres of marshland on the northern edge of the Sandhills. |

He awoke and reportedly told his father, “I knew you would find me, Dad.” Many stories had unhappier endings.

Prairie fires were especially dangerous in grass country. In March of 1921, a fire started south of Martin when a car cushion caught fire and was thrown into a dry road ditch. A strong north wind fanned the flames and it expanded into the Sandhills, burning winter hay supplies that were badly needed.

After major fires, ranchers had the soul-wrenching task of traveling across the land to find and shoot any cattle and horses that were too badly burned to live.

Oscar Greenough, a pioneer rancher, wrote in the Bennett County history book about a fire that started in a place called Buzzard Basin in 1925. “You could see fire in every direction,” he remembered. “The fire was moving many miles an hour with the 50-mile-an-hour wind behind it. People trying to fight the fire would have to run their horses to keep ahead of it. That evening when the wind changed, it looked like the heavens were on fire. The light showed above the smoke and dust. Some people believed the world had come to an end.”

Blizzards were another worry. Joy Fairhead wrote in the history book about a 1919 spring storm so furious that, “you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.” The Fairheads helped a neighbor. “We rode to White River. There we found 200 of his steers, also a bunch of range horses. They had mud and ice all over their backs and tails. We headed back to Dead Man’s Lake and found 1,000 steers frozen in … they looked like sardines in a can.”

Most of the steers were alive. The Sandhills cowboys spent a full day trying to rope and pull the animals out of the icy lake, and rescued about 100. They were able to drive out about 25 more by kicking and yelling. “We were near freezing so we gave up and went home,” Fairhead wrote. “Our chaps, Levis and underwear were all ice and mud. We couldn’t get out of them until we thawed out around the living room stove.”

When they returned early the next morning, half of the remaining steers were dead. Those still alive were barely able to bawl. “We didn’t have the heart to try again,” Fairhead wrote. The tragedy was reported in newspapers across the United States.

But before the carcasses thawed, hundreds of Native Americans came from the Rosebud and Pine Ridge reservations to butcher the frozen beef. “The weather was nice, and they started skinning,” wrote Fairfield. “There was jerked beef all over the wagon wheels, wagon tongues, ropes, wire fences. It was sliced real thin and dried.”

Fairfield wrote that Native American families were a big part of Sandhills history. “One of the highlights was gatherings the Indians liked to have they called Indian Fairs. They would have horse races and dancing. We boys and a pal fixed up a wagon with a tent and a box for our eats. The first one I attended was about September 1910, north of Lacreek. Our neighbors were White Rabbits, Bad Wounds, Bad Hairs — all fine neighbors and it was a good place to live.”

South Dakota’s Sandhills lie in the southeastern corner of Shannon County on the Pine Ridge Reservation and extend into the southwest corner of Todd County on the Rosebud Reservation. But most of the South Dakota Sandhills lie in Bennett County. The Little White River — once known as Stinking Water Creek — runs along the north edge.

“The South Dakota Sandhills are unnoticed, overlooked and unheralded,” says John M. Crowley, professor emeritus at the University of Montana in Missoula. Crowley explored and wrote about the region, and was surprised by the lack of attention it receives. He says the South Dakota Sandhills differ from Nebraska’s in three important ways. “The South Dakota Sandhills have no towns, few roads and few ranch headquarters, whereas the Nebraska Sandhills have many of all three of these. The South Dakota Sandhills do not have a single town and never did.”

Martin residents seem surprised when asked about the Sandhills. The town has never marketed the history or the geology, though the town of 1,000 people certainly could declare itself the Gateway to the Sandhills. The Lacreek Refuge, southeast of town, is the only opportunity for visitors to learn about the land.

To further study the Sandhills, a South Dakotan needs to drive U.S. Highway 73 across the Nebraska border toward Merriman, Neb., (pop. 128). As soon as you leave South Dakota, you’ll find the Bowring Ranch, a state park that preserves the history of Sandhills ranching. The ranch was owned and operated for many years by Arthur and Eva Bowring. She was Nebraska’s first female U.S. Senator. The Bowrings’s humble ranch buildings and their white-faced Hereford herd of cattle are all still there, along with exhibits of ranch life amidst the cactus and yucca. Merriman, just south of the Bowring Ranch, is a tiny place with several farm stores, a cafe and a few churches.

The Sandhills were formed in about the same era as when the Paleo-Indians, the first human inhabitants, arrived about 12,000 years ago. They hunted mammoths and other species that became extinct in the Archaic Period. Archeologists have explored and excavated numerous fossil sites in both states. Often, fossils and artifacts are found when the sand dunes are exposed by wind or water. Ranchers call such events a “blowout.”

Only man and bison survived. Man nearly killed the bison in the late 19th century, but now the ancient beasts thrive on tribal lands, Turner’s empire and local ranches.

But the real survivors are the Sandhills themselves. They’ve been laid bare by droughts, tromped by mammoths and sculpted by wind and rain. Yet they endure as one of America’s most unusual and imperilled terrains.

And they begin in South Dakota.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2014 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments