The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

McMaster's Gas War

Aug 28, 2013

|

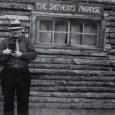

| South Dakota's tenth governor, William Henry McMaster, took on Standard Oil in the 1920s. |

South Dakota’s tenth governor, William McMaster, generated headlines in the 1920s when he fired the first shot in a Midwestern gas pricing war.

McMaster never related exactly what was going through his mind as he watched President Warren G. Harding's casket carried up the steps of the U.S. Capitol in August 1923. Certainly the governor could be forgiven if his thoughts drifted once or twice from the eulogies of the day to the strategies of coming days. For as soon as Harding's casket was placed aboard a train bound for Ohio and burial, McMaster would board another bound for Chicago and a fight.

Back home in South Dakota, with harvest approaching, gas was retailing as high as 26.6 cents a gallon. To put that into some perspective, South Dakota's annual per capita income stood at about $400, and a new Ford Model T touring car cost $295. South Dakotans owned 121,149 cars and 10,554 trucks; while tourism by automobile was just in its infancy, everyone knew that gas prices farmers paid to haul goods to market profoundly affected farm profits and the state's overall economy.

McMaster, a Republican who was a Yankton banker and financier by profession, knew all about profits. He was for farmers making profits, as well as oil companies, he said. But he had deep concerns about the extent of oil companies' profits.

The governor checked into Chicago's Hotel Morrison and told reporters he would meet with Standard Oil officials and say, by his calculations, they could reduce prices by ten cents a gallon and still make a healthy profit.

At the meeting he lowered the boom. If Standard Oil didn't sell at 16 cents a gallon, the State of South Dakota would begin selling 60,000 gallons at that rate, filling private cars and 50-gallon tanks on farms.

No, he said, the state wasn't supplying gas at cost, which would be unfair competition. Sixteen cents represented two cents more per gallon than South Dakota was paying for its bulk supply.

"They (Standard Oil) said they will lose money," McMaster told reporters. "My answer to the Standard Oil is 16 cent gas for South Dakota. 1 am calling upon surrounding states to join in the fight which will be waged to the bitter end."

What would happen when South Dakota's initial 160,000 gallons were exhausted? "A new order for half a million gallons will be on the way," McMaster promised, "provided we don't get some assurance by that time that a permanent price cut will be made."

North Dakota was the first state to take McMaster's challenge and join the fight. Governor R.A. Nestos announced his state, too, would sell gas "until dealers cease their exorbitant charges."

A day after the McMaster meeting, Standard Oil agreed to drop prices to 16 cents. But it grumbled to the press, issuing a statement: "This company asserts such price is below the cost of manufacture and distribution. However, Standard Oil has always stood upon the principle that the customers who purchased its goods should never be compelled to pay a higher price than that maintained by any competitor... "

The fact that this particular competitor was a state had some legal experts scratching their heads. Nebraska Governor Charles Bryan said he needed time to study legalities before endorsing state sales there. That prompted residents in Omaha to push for an amendment to their city charter, allowing Omaha to sell gas just as it sold coal. In Iowa, Governor N. E. Kendall said he was conferring with his attorney general and added, "1 have requested Governor McMaster to furnish me the basis for his action."

Regardless of what their governors did or didn't do, all heartland states saw gas prices plummet. After all, a company like Standard Oil couldn't expect the public to accept a wide price disparity between, say, Sioux City and Sioux Falls. That fall it was possible to buy 3 cent gas in Des Moines. Oklahoma briefly saw five cent gas.

Nobody watched the situation in South Dakota more closely than leaders of the nation's 300 automobile clubs. Those clubs claimed enough members to wield real political clout. But members were divided; some said clubs should lobby for more federal regulation of gas pricing, while others argued that action would hurt small independent dealers and ultimately allow big companies to charge still more.

Now it wasn't the federal government, but South Dakota's that was doing something about pricing. Was the strategy putting a squeeze on independents?

No, said L. V. Nicholas, speaking for independents as National Petroleum Marketers president. He believed Standard Oil wished to "crush independent dealers" but that McMaster's plan leveled the playing field by sparking a price war on South Dakota's terms and timetable, not Standard's.

"Governor McMaster's plan is bound to accomplish good, constructive results," Nicholas said. F. G. Allen, president of South Dakota independent dealers, agreed.

The state stopped selling after major oil companies agreed that 16 cents would be the South Dakota base price. Gas mostly retailed at 15 or 16 cents through harvest, but in early November the price unexpectedly jumped two cents. If prices didn't fall back to 16 cents by November 19, McMaster said, the state would sell gas again, this time at 14 cents. The prices dropped, but not until state gas had been pumped.

For two years, the state was tested now and then by big oil companies. Each time the state started selling. There were calls for a special legislative session to set a policy, and in 1925 state lawmakers in regular session gave the Highway Department authority to sell petroleum products when the governor or other officials deemed it necessary.

Then in October 1925 the state Supreme Court ruled state sales unconstitutional. By that time McMaster was a U.S. senator. During his single term in Washington McMaster often banded with other rural legislators to fight what they considered abuses by big business.

Unconstitutional or not, McMaster told colleagues he figured he saved midwesterners $150,000 in 1923.

Editor's Note: This story is revised from the March/April 1995 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments