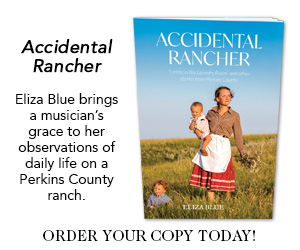

The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Murder of Patsy Magner

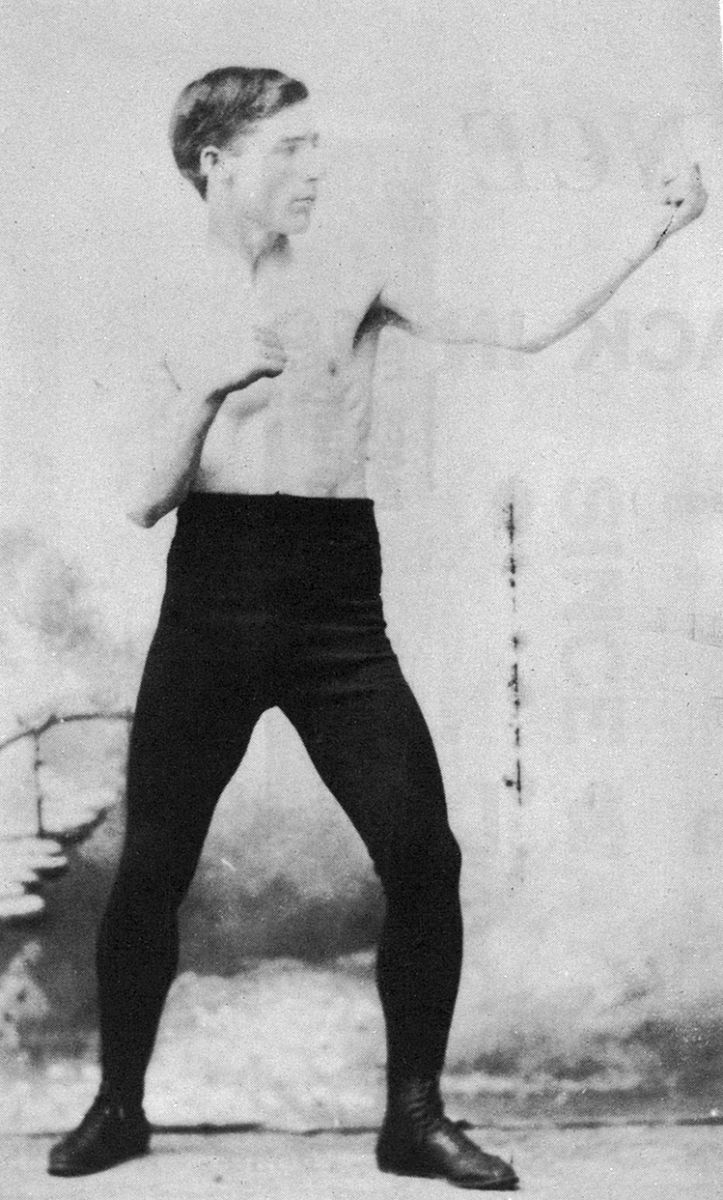

|

| Patsy Magner's scrappiness served him well as a young boxer, and through life. He parlayed his sporting prowess into the gambling and liquor arenas of early-day South Dakota. Photo courtesy of the Dakota Territorial Museum. |

Cold cases are often neatly resolved within an hour on television. In real life, they mostly stay cold. Families mourn without resolution. Perpetrators remain at large. Communities wonder whether a killer walks among them. Such was the murder case of Yankton’s Patrick “Patsy” Magner.

David and Mary (Creighton) Magner came to America during the great Irish migration of the 19th century. They married in Woodstock, Illinois, where David earned his living as a shoemaker. Patrick and his elder brother Michael were born in Illinois, but they came of age on the frontier because, like many of his countrymen during that era, David Magner was a restless soul. In 1872 he headed for Yankton, Dakota Territory, and set up his cobbler’s bench.

David passed away two years later, when Patsy was 7 years old, leaving Mary to raise two young boys. “Little is known of [Patsy’s] growing-up years,” wrote historian Bob Karolevitz, “but by his early 20s he was already a professional fighter.” Magner compensated for his slight build with ferocity, a characteristic that came to the fore during his most notable bout — in 1899, before a crowd of 500 at the Sioux City Athletic Club — against one-time world featherweight champion ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy.

“In the first round Magner used foul tactics, and Murphy also began to rough it,” reported the Sacramento Record Union. “In the second, when the police intervened, the men were fighting like dogs on the floor of the arena.”

Prize fighting was illegal in Sioux City, so Murphy, Magner and the fight’s promoters were hauled off to jail. This wouldn’t be the last time Magner ran afoul of the law. Almost by default, boxing put him in touch with unsavory types, especially gamblers; it is easy to see how he drifted into schemes and ways mentioned with disfavor in the statute books. From then on almost all of Magner’s various enterprises, even the strictly legal ones, had a whiff of malfeasance about them. His murder shocked Yankton, but few people in town would have been entirely surprised that he came to a bad end.

Yet he was always a popular, charismatic figure. In a rose-tinted recap of Magner’s life after he died, the editor of the Yankton Press & Dakotan wrote that, “many older citizens remember when, during his pugilistic career, he used to walk down the street and, seeing a group of boys pining to get into the theater, would pay the admission for the entire crowd.”

Magner did have one legitimate outlet for his athletic ability. Yankton’s fire brigade in the 1890s was organized around five hose teams, “and competition among these was very keen to see who could recruit the most prominent citizens,” according to the Yankton County History. As a well-known fighter, Magner would have been a prize recruit, and he was no mere show horse. At the South Dakota fireman’s tournament in 1896 Magner served as captain of Yankton’s winning hose cart race team, and he personally won the 100-yard foot race.

From the 1890s through the early 1900s, Patsy Magner split his time between Yankton and Sioux City. Both he and his brother Michael, who were 31 and 33 at the time, were listed as members of their mother’s household in the 1900 federal census. Michael’s occupation was “merchant,” and Patsy’s “button maker,” which is either evidence of a mother in denial or an inside family joke.

Michael and Patsy’s true occupation was operating saloons in Yankton and Sioux City, and they acquired their place in Sioux City after the previous owner was gunned down in the street. “Nobody ever connected them to the crime, but that was the kind of environment they operated in,” said Jim Lane, a Yankton native with a decades-long interest in Magner’s murder.

|

| After Patsy Magner lost his farm in 1915, he bought this small house located along Old Highway 50 near Yankton. |

Gambling went hand in hand with the saloon business, and not always harmoniously. Magner was hauled into court multiple times on related charges, most notably by T.D. Becker, who lost $12,000 in what he claimed was a rigged faro game.

In the course of their protracted legal wrangling, Becker “proceeded to catch the saloon men in a violation of the law [by] hiring Claude Klegin and William Grensel, minors, to purchase liquor from them,” reported the Sioux City Journal. Before the merits of that case could be argued, Magner was found in contempt of court and fined $200; to make matters worse, his attorney, after two hours of “a most bitter denunciation of Becker,” was forcibly removed from the courtroom.

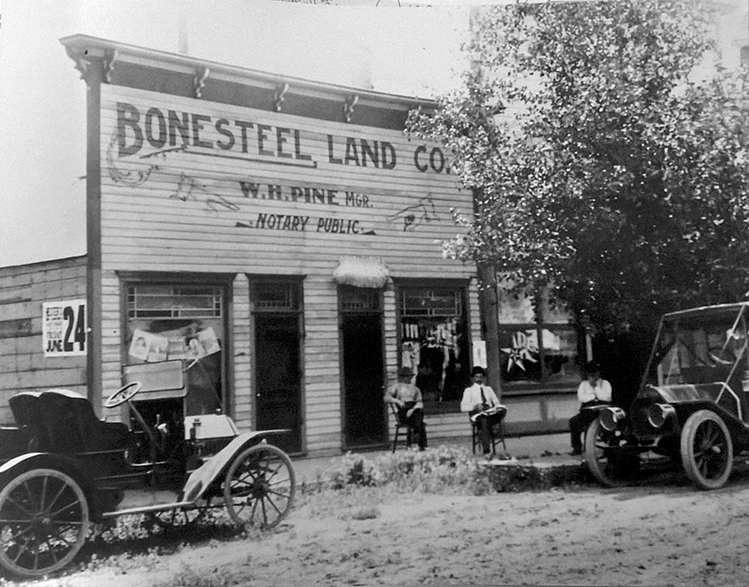

Magner’s checkered history was no obstacle to landing a gambling concession in Bonesteel during the land lottery of 1904. He operated a saloon and managed to thrive while the bad men ran riot; an article in the Norfolk Weekly News-Journal asserted that “crooks reaped a rich harvest of $75,000 for their three weeks trouble. Patsy Magner made $20,000.”

Yet when the town’s troubles multiplied and its citizens sought help they turned to Magner, who adroitly managed the transition from big-time gambler to municipal savior. Account after account of the conflict hailed him for his role in returning control of Bonesteel to “the respectable element.”

Magner shot himself in the foot during the commotion, but in the flush of victory no one seemed to care. He traveled to Sioux City on the same train as Chief Clerk John McPhaul, and according to the Sioux City Journal, the crowd that greeted them, “gave the gambler who cleaned out the town … an ovation upon his arrival.”

George W. Kingsbury published Volume IV of his epic History of Dakota Territory in 1915. He included a short biography of Patsy Magner that made no mention of gambling, liquor or anything unsavory. Kingsbury’s Magner was a progressive farmer who followed “advanced scientific methods” and sent more cattle and hogs to market than all but a few producers in the state.

Magner started with 160 acres in 1902, according to Kingsbury, and added to his holdings until his ranch comprised 520 acres, “on which he has one of the finest sets of farm buildings in Yankton County or in South Dakota.” What Kingsbury neglected to mention was how that increase occurred.

“Magner came into [his land] the old-fashioned way,” Lane says, laughing. “He married Maude Paul, who owned it.”

Maude A. Paul grew up on a Nebraska homestead. After moving to Yankton she purchased a 320-acre farm — an unusual step for a single woman in that era — and ran it successfully before she married Patsy in 1905. Kingsbury conceded that Maude’s, “knowledge of agriculture and stock-raising is equal to that of her husband,” but that assessment would seem to be a considerable sop to Patsy, who was more familiar with saloons than barns.

Nonetheless, Patsy did find ways to contribute to the bottom line. “One of the stories my dad told me was that Patsy used to pay his workers at the farm in cash, then he’d play cards with them, and a lot of times win it back,” Lane says. “Well, one week these two brothers cleaned house, beat him pretty bad, and he flew into a rage. They had to hide out in a cornfield until he cooled down.”

Patsy and Maude also owned a thousand-acre grain farm west of Yankton, but when the census taker came around in 1910 Magner listed his occupation as “liquor wholesaler.” He and Mike operated what they called a “Family Liquor Store” on Yankton’s Third Street, while Patsy and another partner owned a saloon in Bonesteel, where he carried on as he always had.

On Jan. 27, 1910, Bonesteel’s city commission met to discuss whether Magner’s liquor license should be revoked. They were charged with, “selling liquor to men who were blacklisted by their wives [and] carrying on gambling in a rear room,” according to the Norfolk Weekly News-Journal. He managed to retain his license after a vote by the commission, but that result led to one alderman bitterly denouncing another for yielding to Magner’s pressure.

|

| Patsy Magner wrangled a gambling concession in Bonesteel, where the 1904 land rush attracted 104,000 men. |

Magner’s career as a big-time farmer was short-lived. In 1915 he and Maude mortgaged their home place, perhaps to raise money and expand to take advantage of the spike in commodity prices caused by war in Europe. Whatever the reason, it didn’t pan out. Their farm and its fine buildings were sold at a sheriff’s sale just three years later; they moved to a small property on the east side of Yankton, and Patsy began raising show horses.

Worse yet was on the horizon. Prohibition came to South Dakota in 1918, two years before the nationwide ban took effect. Magner’s liquor store and saloons had to close, which likely abetted what happened next. Trapped between their accumulated debt and diminished income, Patsy and Maude were forced to declare bankruptcy in 1921.

Magner listed his occupation as “manager of a soft drink parlor” on the 1930 census form. Given his record, it is difficult to believe he spent the Roaring Twenties serving Yoo-Hoo while fortunes were being made in illicit liquor, especially considering the wide open situation in Yankton, where the county sheriff was reportedly in league with the bootleggers.

In any event, Magner opened a card room and beer parlor, the Blue Fox, in the spring of 1933, just days after President Roosevelt signed a law allowing the sale of 3.2 percent beer. Prohibition ended later that year. To Magner, it must have seemed that happy days were indeed here again.

Patsy Magner's death was reported beneath a headline which spanned the Press & Dakotan’s front page on Dec. 31, 1934: “Patrick (Patsy) Magner, well-known businessman, age 65, was instantly killed about 10 o’clock while sitting in the parlor of his home … peacefully listening to the radio and talking with his wife.”

A coroner’s inquest was convened the next morning, and the first witness was Maude, who appeared “stoically calm” as she testified. “Mrs. Magner said her husband jumped from his chair as he was hit and said, ‘What the H--- is going on here!’ and that as she started to arise from her chair two more shots were fired at her.” Patsy managed to stagger into the bedroom, where he collapsed and died within minutes. Maude ran onto the highway and flagged down a passing motorist, who called the sheriff.

Sheriff William Hickey had little to offer when he testified. He used string to determine that the shots were fired from outside, through a window, but the ground was frozen and so yielded no footprints. All he found at the scene were four casings from a Colt .32 automatic.

Magner’s funeral, officiated by Msgr. Lawrence Link, pastor of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, was held at his home. By the Press & Dakotan’s reckoning, “the procession to the cemetery was a mile long.”

That very day the newspaper published a fire-breathing call-to-arms entitled “Smoke Out The Rat.” In the good old days, wrote the editor, men confronted each other “on the street, in plain view of the town’s people.” Magner, in contrast, was slain from the shadows by a perverted, cowardly rat, “the most stinking, furtive, unsocial and unclean [form] of animal life …. We wish to insist that this is more than a murder. It is the beginning of an obnoxious form of crime that must not be permitted. This ‘rat’ must be found and destroyed.”

By chance, new sheriff William J. Limpo and new state’s attorney Frank Biegelmeier took office one week after the murder. They vowed to vigorously investigate the case, and the county commission offered a $500 reward. But days, then weeks and months went by with no progress.

Scant physical evidence was no impediment to rampant speculation, of course; as with many murders, the first suspect was close to home.

“Grandma said Maude did it,” Lane says. “That’s my family tradition.”

|

| Don Tucker and his wife, Ava, have restored the Magner home east of Yankton. Tucker points to the window through which the murder happened in 1934. |

Patsy and Maude had a notoriously stormy relationship, according to this theory. Maude either did it herself or hired a guy, who left town right after the murder. In line with that explanation, the .32 caliber gun that was used indicates an amateur job rather than a big-time criminal conspiracy, according to Lane. “It’s not a very powerful weapon. A professional hit man probably wouldn’t choose it as his first option to shoot through a window.”

Magner’s past and current business dealings provided ample material for rumormongering. At the inquest, Maude testified “that her husband had intended to dissolve his partnership in [the Blue Fox Saloon] with Fred Fincke,” according to the Press & Dakotan. “She said there had been friction between the two men for some time and that the dissolution was to have taken place that very day.”

Fincke wasn’t called to testify, “and was not questioned by officers aside from being asked if he knew of any acquaintances who might possibly have had a motive for the slaying.” If he had any suggestions to offer they led nowhere.

Fred and Maude, as Patsy’s widow, sold the Blue Fox soon after the murder. That may have been Magner and Fincke’s plan all along, but it’s doubtful everyone in Yankton accepted such a benign explanation. Not when it became known Aage Christensen was the buyer.

“My dad was a big bootlegger,” says Aage’s son, Marvin ‘Pal’ Christensen. “He was partners with the sheriff. They did business all over Iowa, South Dakota and a lot of Nebraska.” Christensen senior owned a barn that served as the pair’s warehouse during Prohibition. “Whenever there was going to be a raid by the state they’d always let the sheriff know. So then he’d call my dad, and he’d get everything cleaned up before they came.”

Christensen went to work as a bartender at the Blue Fox after Prohibition ended. Buying the bar made for a simple transaction on both sides, but Frank Yaggie, one of Aage’s lifelong friends, couldn’t shake the idea that there was more to it.

“When Frank was on his death bed he called me in and said, ‘You know, I got to get this off my chest. We always thought your dad shot Patsy Magner,’” Christensen says. “So I told him, ‘Frank, I don’t know if that’s true or not, but I doubt it.’ Then he died about 10 minutes later.”

Don and Ava Tucker now live in the house where Patsy was murdered. The house and its matching red-brick barn have both been beautifully maintained and restored. Tucker raises Rhode Island Red chickens and goats on the property, which sits on the eastern outskirts of Yankton.

Tucker is well-acquainted with the Patsy Magner story. “He was sitting right where I sit to watch TV,” he says. “I figure it’s safe enough. It’s not like lightning is going to strike twice in one spot.”

Tucker has had many conversations about Magner over the years, including several interesting discussions with Jerry Bienert, now deceased, a long-time county commissioner and storehouse of local history.

“Jerry said he tried to follow up [Magner’s murder] and figure out who did it, but he just kept getting stonewalled,” Tucker says. “It never went anywhere.”

Bienert did come across a rumor that the shooting was over Patsy Magner’s involvement with a young woman from a well-connected Yankton family, which could explain why the investigations always stalled.

So it goes when a crime remains unsolved. Every theory sounds plausible to someone, and they all have only one thing in common.

“Somebody just did it,” Tucker says, “and went on with their life.”

Editor’s note: This story is revised from the January/February 2016 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments