The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

David Wolff’s Black Hills

|

| David Wolff spent 17 years teaching history at Black Hills State University in Spearfish. His new "Black Hills History Tours" book series blends travel with the region's most colorful historical stories. |

Every mountain range needs a few curious historians. They help the rest of us appreciate the peaks and valleys.

David Wolff of Spearfish fills that role in the Black Hills, and now the former professor is embarking on a six-book project that will not only recount the region’s colorful history but also serve as a guidebook for those who share the author’s itch to explore.

Mountain towns also need pharmacists — and that’s where Wolff got his start. Forty years ago the Denver native who was raised in Wyoming was working the pharmacy counter at a Pamida store in Sturgis. He wrote a history paper as an amateur and took it to a conference organized by university historians. “Pharmacists wear ties and that’s what I wore to the conference, and the history professors moved toward me when I arrived, assuming I was one of them,” Wolff recalls. He sensed they were less enthusiastic in greeting an amateur when they learned his identity.

The pharmacist eventually left the Black Hills, off to greener medicinal pastures, people in Sturgis surmised. In fact, he left to study history, first at the University of Wyoming where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and then at Arizona State University where he gained a Ph.D. In 1998 he returned to South Dakota to teach at Black Hills State University. He became Dr. David Wolff not as a matter of pursuing a personal goal or for job security (no one will tell you a historian’s position is more secure than a pharmacist’s). Rather, Wolff became a historian because he considers the field vital, especially the multi-layered history of the Black Hills and its mining culture — a significant component to American history overall. And yes, the snub he sensed at that long-ago conference was a motivator in reinventing himself. He didn’t want the lack of academic credentials to limit his ability to reach the public through university offerings, writings and at local history society talks that are free and open to all.

“He comes across as an everyday person,” says photographer and author Paul Horsted, creator of books with photos that compare and contrast historic and modern images. “But he’s got such a depth and command of knowledge at his fingertips, especially gold rush history and what happened afterward. As I was feeling my way in learning that history, David was so kind in being a sounding board.”

When Horsted mentions Wolff’s depth, he could include his friend’s recognition of romance in even the gritty business of mining. Wolff remembers the soft glow of light emanating from windows in Deadwood and Lead’s mining mills, reduction plants and slime plant at night as his family vacationed there — “evidence of workers’ massive efforts, round the clock, in grinding out wealth from the earth,” he says. The Wolffs lived in Cheyenne, Wyoming, when he grew up. His dad was a traveling salesman, mostly supplying drug stores. David sometimes tagged along and that was his introduction to pharmacists — nice people and important members of their communities. Wolff’s parents encouraged him to pursue pharmacy himself. Sure, they knew David’s interest in history and his love for Wyoming’s past as documented throughout the capital city and at nearby Fort Laramie.

“But nobody in the world I grew up in thought you could make a living in history,” Wolff says. Still, the idea briefly crossed his mind in college after reading Watson Parker’s classic Gold in the Black Hills. Wolff wrote to Parker, a history professor at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, and Parker replied. He thought Wolff might be better off using money that would cover tuition for building a personal library of good books delving into history.

If Wolff got a delayed start as a historian, he more than made up for it — and continues to do so with an agreement with the South Dakota Historical Society Press to author six books in the coming years that will combine Black Hills driving with learning history. He taught 17 years at Black Hills State, a period that overlapped 18 years as a member of the South Dakota State Historical Society board of trustees. Still, the term he feels best describes him is simply “a history buff.”

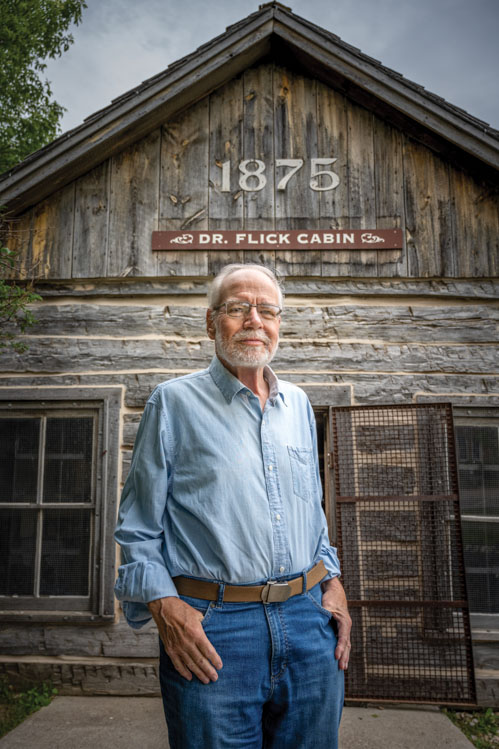

Which is exactly how he comes across sitting in downtown Custer’s Way Park talking to a couple friends about historic cabins. Specifically he mentions this park’s Daniel Flick cabin, long proclaimed as the first built in the Black Hills. And that may be, Wolff says, although it’s unlikely the structure would pass a test by modern historians for such designation. Judge Henry Way pretty much declared the Flick cabin as first while developing the park across the street from the county courthouse in the 1920s. “That was fifty years after the presence of gold in the Black Hills was first confirmed in Custer,” Wolff says, “and the men and women who were here soon after gold discovery were aging and wanted credit for what they built. Almost every town in the Black Hills had its cabin.”

|

| Wolff met with author Paul Higbee (right) in Custer's Way Park. Despite his long academic career, Wolff says the title that best describes him is "history buff." |

Wolff believes the demand for credit by pioneers is more interesting than whose cabin came first. And while the Black Hills claimed structures more impressive than those humble dwellings — especially its great mines — there was something uniquely American about log cabins. They seemed to assert the Black Hills had become part of America rather than uncharted territory.

“There are a lot of myths and mistakes in history,” Wolff says. “I started out thinking I could correct those things. But misinformation hangs on so tenaciously.” People tend to believe what their families told them as kids, whether they lived in the Black Hills or visited as tourists. Embellished tales survive because they incorporate good storytelling techniques. Deadwood, most South Dakotans understand, has spawned myths since its founding in 1875 and 1876, and the HBO series Deadwood, which ran from 2004 to 2006, took that mythology to new heights. Wolff, frequently asked to comment on the series during its run, understood it as historical fiction and not a history lesson. “Something I looked for in the show, though, was whether or not it remained true to the personal qualities of the historical characters it portrayed,” Wolff says. “And I think it mostly did.”

For example, take Deadwood’s first sheriff, Seth Bullock. The series’ writers and actor Timothy Olyphant created a lawman who was mostly hands-off when it came to little things. “That was authentic to Bullock,” Wolff says. “He didn’t go after the drunk and disorderly and thought that celebrating by shooting into the air was okay.”

Wolff accepted an invitation to discuss Bullock on the Discovery Network’s Gunslingers series. It turned out well although he had to tell producers there’s no evidence that Bullock slung his guns or engaged in shootouts. And the program prompted this question: What does a professional historian facing TV cameras look like? It seems there’s a school of thought that says anybody living in the West and writing its history must be so enmeshed in the culture that they dress in character. “The Discovery Network asked me to show up with my look,” Wolff recalls. “I don’t have a look,” and he didn’t invent one for the appearance.

Wolff accepted another invitation related to Bullock, this one from the state Historical Society Press to write a biography, Seth Bullock — Black Hills Lawman. The book came out in 2009 and addressed aspects of the subject’s life that were not fodder for a TV shoot-em-up: personal friend of Teddy Roosevelt, government official who worked to establish Yellowstone National Park, federal Black Hills Forest Reserve (today’s Forest Service) superintendent, ranching innovator and Belle Fourche founder.

Wolff’s next book for the Historical Society Press profiled a remarkable Deadwood man, James K.P. Miller, strangely forgotten by history. Even Watson Parker told Wolff he never heard of him, although when Miller died at age 45 in 1891 a local paper predicted “his name will always be coupled with the prosperity of Deadwood and the Black Hills.” But it wasn’t, and no one was more instrumental in retrieving it than Wolff 130 years later. Among tools Wolff worked with in exploring Miller’s life and times was newspapers.com, technology that didn’t exist when he wrote the Bullock book. Miller was a native New Yorker, frontier grocery proprietor, builder of Deadwood’s Syndicate Block, and a wheeler-dealer who brought two railroads into Deadwood by setting up something of a competition between the Fremont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley Railroad and the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad. “Sometimes we forget,” Wolff says, “how competitive railroads were back then. They hated each other.” Miller apparently understood that industrial hatred and made it work for Deadwood, which became one of a select number of South Dakota towns served by two railroads. Very likely that saved Deadwood from deteriorating into something unrecognizable and beyond rehabilitation in the years after the gold rush.

Without Miller, would there have been Days of ’76 celebrations, today’s gaming industry or the Deadwood TV series? Maybe not. The Miller biography, The Savior of Deadwood, James K.P. Miller and the Gold Frontier, was published in 2021.

|

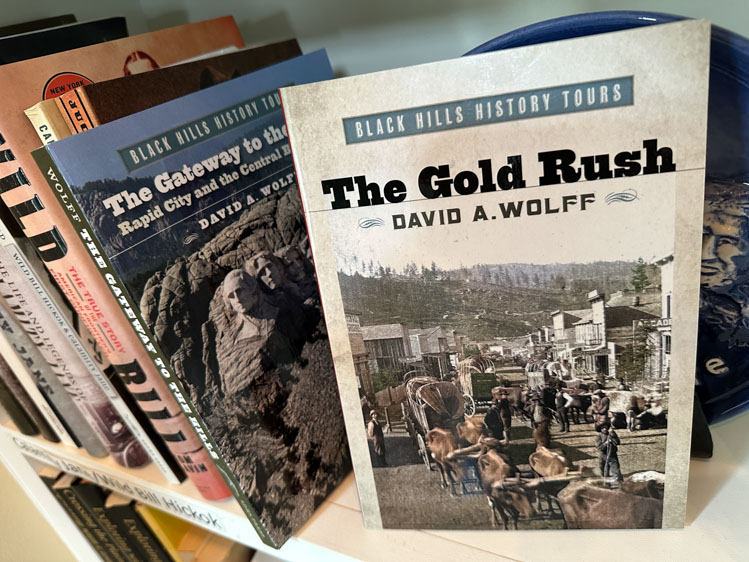

| The Gold Rush and The Gateway to the Hills are the first two installments of Wolff's "Black Hills History Tours" series. |

Wolff’s new book, The Gold Rush, is far from a biography. It resembles the Works Progress Administration’s state guidebooks of the 1930s, with more detail yet retaining a thumbnail listing format. The book identifies driving routes from Custer northward (later volumes in the series will take travelers elsewhere through the Black Hills and surrounding plains), identifying historic locations along the way. “It is a travel book,” Wolff says, “but I don’t recommend places to stay or eat. It’s all history.”

It’s history that is found along roads accessible by regular cars — no ATVs required. Among the author’s favorite sites, most retaining an air of historical mystery, are the Flick cabin and the so-called China walls at Galena (on Galena Road off U.S. Highway 385 south of Deadwood). Galena was best known for its silver mines in the 19th century but in 1909 it was announced that the area held great quantities of copper. Construction began on a copper mill but only stone walls, impressively crafted, were completed. “It has become commonplace,” Wolff says, “to look at old rock work and mistakenly assume Chinese did it.” Indeed, Chinese laborers contributed to much construction during the Black Hills gold rush early on, but by 1909 few remained. Was there really a copper fortune to be mined at Galena? No, says Wolff.

There was no shortage of nefarious mine developers who attracted naïve investors to sink money into operations that would never yield profits. Three-and-a-half miles below today’s Pactola Dam, about 10 miles west of Rapid City on Highway 44, the Fort Meade Hydraulic Gold Mining Company (perhaps named for Fort Meade army officers who invested) began blasting a tunnel to move water for a sluice box that would work supposedly gold-rich gravel. The company’s very real tunneling, done from 1879 to 1882, probably kept investors engaged, but it closed. Soon, another company picked up the work, also relying on investors, but disappeared in 1889. Not much gold was recovered. What remained was a tunnel moving swiftly flowing water and an underground falls, later illuminated with electricity and named Thunderhead Falls for tourists. The attraction is permanently closed now, but the inspiring natural setting of cliffs and rushing waters makes it easy to see how investors thought something good was bound to take root.

Another site Wolff introduces is one the Forest Service calls the “only gold mining site on the BHNF (Black Hills National Forest) with a standing mill frame.” That’s the Gold Mountain Mine, northwest of Hill City down Burnt Fork Road. Lots of infrastructure work was done there in the 1920s and ’30s. “There is, however, no record of production,” Wolff says. That didn’t stop the Black Hills Historic Preservation and Trust Society from deciding to preserve the mill, rock work and exterior boilers a few years back, with volunteers and students from the Boxelder Job Corps Work Center, joining the effort.

This is a travel book, yes, but it will undoubtedly reach armchair travelers around the world and find use as a well-organized reference. A glance reveals the remarkable range of historic personalities connected to the Black Hills across the years, from giant American industrialist George Hearst (who developed Homestake, the western hemisphere’s biggest gold mine at Lead) to Lakota traditionalists committed to retaining a modern presence. Wolff is certainly describing more authentic Indigenous historical views than the WPA writers and in part credits landing on the faculty of Black Hills State, a university committed to Native course offerings and its Center for American Indian Studies. In particular he appreciated his late colleague Jace DeCory, a widely respected Lakota elder and teacher. “She was invaluable in helping me understand Lakota perspectives, and was always balanced and thoughtful,” Wolff says.

The book was released this summer, and surely readers will want to collect the entire series of six. They won’t wait long. There’s a chance the second will come out later this year, and Wolff and his editor and designers are working at a pace that could see two more published in 2025 and the remaining two in 2026. Upcoming books will address the Lawrence County triumvirate of Deadwood, Lead and Spearfish, Rapid City and the central Hills, the southern Hills, the Belle Fourche River and Wyoming Black Hills, and what Wolff calls “unknown, under-told or under-appreciated stories.”

The Black Hills delight people who sometimes declare they’ve found a pristine natural environment. But travel with David Wolff and you’ll see it’s a rare patch of the Hills that hasn’t been touched profoundly by humans — Lakota defenders, the U.S. Army, railway builders, miners, loggers, engineers who transformed land and water, town builders and, after devastating fires, town rebuilders.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2024 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments