The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Real Hero

|

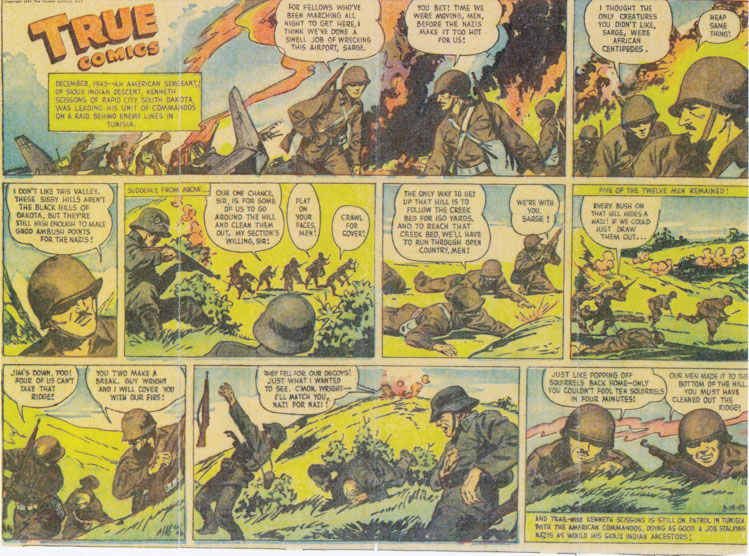

| The World War II heroics of Rapid City's Kenneth Scissons became wonderful content for comic books of the era. |

Superman crash-landed in a Kansas wheat field in 1938. Batman, Green Lantern, Wonder Woman and their archenemies soon followed, and together they ushered in the Golden Age of comic books.

George Hecht and the Parents’ Institute swam against the superhero tide by launching True Comics. Hecht and his editorial advisory board published 84 issues from April of 1941 through August of 1950, believing that children might also like stories that were exciting and factual. Each issue carried a banner that proclaimed, “Truth is stranger and a thousand times more interesting than fiction!”

Hecht celebrated real live heroes: World War II raider Jimmy Doolittle, baseball star Stan Musial, inventor Thomas Edison and President Theodore Roosevelt. He found another in Sgt. Kenneth Cuthbert Scissons, a Lakota-English-Norwegian soldier from Rapid City who became a one-man army during World War II, a man the Nazis specifically targeted for capture, and a man whose seemingly superhuman exploits made him the epitome of Hecht’s real comic book stars.

Scissons was born on a ranch south of Colome in 1915, but came of age in Rapid City, where his father, John, worked for the Warren-Lamb Lumber Company. His Lakota lineage stretched back to his grandmother, Hannah Mule, twin sister of Little Big Man, the renowned Oglala Shirt Wearer from Crazy Horse’s band.

Scissons attended Rapid City Indian School through sixth grade, navigating the sometimes-treacherous ways of boarding school. “Dad said a lot of the bigger boys picked on him when he first started,” says Ruth Ahl, Scissons’ oldest daughter. That stage soon passed as Scissons proved to be a natural athlete who excelled at every sport, including boxing.

|

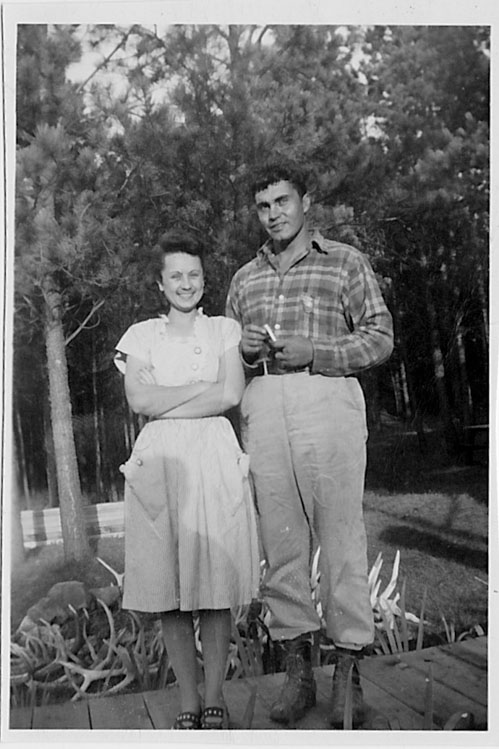

| Wearing a bull snake necklace was likely tame for Scissons, who took heavy fire from Nazi troops during one particularly harrowing battle. |

In seventh grade Scissons transferred to public school, but his formal education didn’t end well, according to Sharon Schaefer, Ahl’s younger sister. “What I picked up is that he was part way through his senior year and got into it with his basketball coach,” Schaefer says. “After that he just said, ‘I’m not going back.’”

Scissons’ first job was at Warren-Lamb; he spent 10 hours a day shoveling sawdust into boxcars, and was happy for the opportunity. “Times were tough,” he later recalled. “If you ever stopped and put your shovel down somebody else would pick it up, then you no longer had a job.”

When Warren-Lamb cut back during the Depression, Scissons joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and was posted to a camp near Hill City. He stood a stout 6 feet by then, and had energy to burn. At day’s end, when the other workers clambered into trucks for a ride down the winding mountain road to their base camp, Scissons would set off cross-country, racing over the rugged mountain terrain on foot.

“He ran so fast he thought his heart was going to burst,” Ahl says, “and he was always at the camp, leaning against a tree, smoking a cigarette when they got there.”

Scissons met Melvin “Tuffy” Cory while he was with the CCC. One day Cory showed Scissons a picture of his sister, Evelyn. “My dad looked at the picture and said, ‘This is the woman I’m going to marry,’” Ahl says. “Everybody thought he was nuttier than a fruit cake.” Scissons had the last laugh, though; he and Evelyn met in the spring of 1937, and were married two weeks later.

Evelyn’s parents didn’t learn of the wedding until a relative sent them a clipping from the Deadwood newspaper. “My mother was working in Mitchell at the time,” Ahl says. “Grandma and Grandpa Cory drove there to see her, and Grandma said, ‘Well, hello Mrs. Scissons.’ My mom tried to explain things, and told them Dad was a Sioux Indian. Grandma Cory started crying and said, ‘Are you going to live in a tee pee?’”

Grandma Cory’s worst fear was never realized: the newlyweds’ first home was a snug one-room house that Scissons and his father built on New York Street in Rapid City.

Scissons hunted and fished in the Hills to put food on the table, and supplemented his CCC income by playing in a band for dances held in Hill City; he played saxophone, clarinet, piano and guitar, thanks to lessons he took at the Indian School. These attracted rowdy crowds, and Scissons felt right at home.

“One night Mom and Dad were walking down the sidewalk, and some guy wouldn’t step aside after Dad said excuse me,” Ahl says. “The guy said, ‘I’m not stepping aside for any damn Indian!’ Dad hit him so hard he flew into the middle of the street. A couple days later the police came to the house and told Dad that the guy had not regained consciousness, and if he died Dad would be charged with murder.

“Thank God the guy came around.”

|

| Scissons and his wife Ruth were married two weeks after they met. |

Scissons joined the South Dakota National Guard in 1936. After basic training he was assigned to the headquarters company of the 109th Engineering Regiment in Rapid City.

Scissons signed up for a second hitch three years later, a perilous moment in history. Germany overran Poland in the fall of 1939, plunging Europe into a war that many Americans feared would soon be at their doorsteps. Scissons and every other volunteer surely understood that the Guard might soon require more of them than one weekend a month, but they signed up anyway.

“Dad was extremely patriotic,” Schaefer says. “He believed in doing whatever was necessary to protect the country. That was how he was raised. You were loyal.”

With war on the horizon, Scissons and five other soldiers from the 109th — Leroy Anderson, Jerry Gorman and Richard Griffin of Sturgis, Bill Turner and Andrew Hjelvik of Lead — volunteered for federal service and were shipped overseas almost a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor. They were among a contingent of Americans who trained with elite British Commandos and took part in raids on occupied Europe, the idea being that they would rejoin their old units when U.S. forces formally entered the war. Their combat experience would season the mass of green troops.

Scissons tried to transfer into the Army Rangers, an American battalion modeled on the Commandos, when it formed in mid-1942; his athleticism and outdoor skills would have fit perfectly within the unit, which specialized in operations behind enemy lines. However, the Rangers only accepted single men.

When the Allies invaded North Africa on November 8, 1942, Scissons was put ashore at Algiers, Tunisia. His first taste of combat came during a raid against the German-held airfield at Bizerte — a mission that blew up almost immediately when the attackers met heavy resistance and withdrew. Scissons was with a squad assigned to safeguard the force’s line of retreat, and their part of the plan also went sideways: they got ambushed and were embroiled in their own firefight.

“[German soldiers] pinned us down with tommy-gun fire from the ridge,” Scissons said in an account of the engagement carried in the Rapid City Journal and dozens of newspapers across the country. “I told our leader our only chance was to go around the hill and clean them out.”

Scissons and his comrades had to cross a stretch of open ground to get where they needed to be. “I didn’t stop to look behind me [as I ran] but when we reached a creek bed only five of our original 12 were left,” he said. “We got halfway up when we ran into more tommy-gun fire and lost another man. As we were down to too few to take the ridge we decided to withdraw.”

Scissons and Guy Wright, of Oklahoma, provided covering fire while Jerry Gorman and another soldier started back down the hill. When German soldiers rose to fire, “we really went to town on them,” Scissons said. “It was like popping off squirrels … every time I pulled the trigger over went a German.”

Scissons earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest military decoration, in just over 4 minutes that day. His account of the firefight sounded much less heroic than the official citation:

“Upon the ambush of his unit by the enemy, Private Scissons, seeing two of his comrades attempting to crawl to safety, did, without regard for his own life, engage the enemy with his rifle and draw their entire fire upon his position. Only after his comrades reached safety did Private Scissons attempt to withdraw, having accounted for approximately ten enemy soldiers. His coolness and courage under fire, and his desire to sacrifice himself, if necessary, for the safety of his comrades are a profound inspiration to members of the Armed Forces, and reflect the highest traditions of our country.”

|

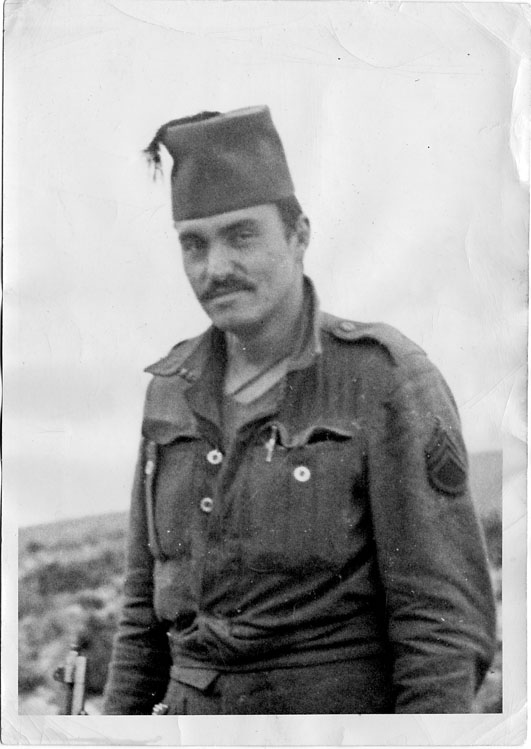

| The Nazis dubbed Scissons "Mustachio Commando" because he always wore a handlebar mustache. |

Most of the attacking party died or were captured that day, and the airfield suffered no damage. Scissons and his squad managed to escape through country “swarming with groups of Germans,” he recalled. By the time they made it to friendly territory four days later, Scissons had lost, “everything but the shirt on my back, but what I missed most were the pictures of my wife and three-year-old daughter Ruth.”

Scissons’ story didn’t need embellishment to earn him a Distinguished Service Cross, but True Comics tweaked the tale for their young readers. In its version, the Bizerte raid was a smashing success, Scissons talked like an Indian from a western movie and he was a sergeant rather than a private; the last was a forgivable inaccuracy, as he seldom remained one or the other for long.

Scissons earned four Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart, in addition to the Distinguished Service Cross, during his time in service. He was a good soldier in every respect but military discipline — a shortcoming that could be attributed to his pugnacious character, the very quality that made him an exceptional warrior.

“Kenny was a one-man army over there,” said Chuck Cory, who served with him in Tunisia. “He’d leave base and we’d never know when he was going to come back.”

Scissons infiltrated enemy outposts, struck silently, and then left a calling card to demoralize the rest. The Germans paid Scissons the ultimate compliment by hanging wanted posters of him across Tunisia; they dubbed him “Mustachio Commando” because he always wore a handlebar mustache.

When the Allies landed at Anzio, Scissons was asked to penetrate enemy lines and capture Germans for interrogation, an assignment he called his worst of the war. Month after month of mortal danger and operating on his own left him with little patience for rear echelon types, even those who outranked him.

“Dad went through hell over there,” Ahl says. “My understanding was that he had several court martials. My mother said she always knew when he was fighting because it was Sgt. Scissons. When he was back at base it was Pvt. Scissons.”

Scissons returned from overseas in the spring of 1945, but his first stop wasn’t Rapid City. “Dad spent six weeks at a base in Texas,” Ahl says. “He was a trained killer, so they thought they had to mellow him out, I guess … you don’t just come right back to your family after something like that.”

Scissons entered law enforcement as a conservation officer with the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks Department. After 20 years, he finished his career as a criminal investigator with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Scissons died on September 9, 1973. Ahl received many condolences upon her father’s death, including letters from Gov. Richard Kneip and longtime South Dakota promoter Almon “Hoadley” Dean. “I had the greatest respect for your father,” Dean wrote. “He was a gentleman, a patriot and a true warrior, held in high esteem and respect by all who knew him.”

No hero — real or fictional — could ask for a better epitaph.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2019 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments