The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Sailing by Balloon

|

| Balloonists at the Great Plains Balloon Race in Sioux Falls. Photo by Greg Latza. |

The summer solstice sun rose above Beaver Creek as Kay West and her crew rolled out a red and yellow ribbon of rip-stop nylon that, once inflated, would lift her and three passengers above lingering pockets of fog and carry us north on a gentle morning breeze. “Most pilots don’t have to assemble their aircraft before they fly,” she jokes. She dragged a fan to the serpent’s mouth and fired up the generator. Little by little the fabric rose, assuming the elongated egg shape of a hot air balloon.

Still yawning from a 4 a.m. wake-up, I waited in the parking lot of Beaver Creek Nature Area southeast of Brandon with passengers Jessica Hudson and Justin Kuipers of Brandon. For years I had gazed up in envy as balloonists floated silently overhead, sometimes unaware of their presence until the blaze of propane caught my ear. I once drove the chase vehicle for friends in flight. Finally, it was my turn to ride.

West had checked her contacts at the National Weather Service and FAA Flight Service, who predicted a southeast breeze on the surface, with a westerly shift atop the temperature inversion, the calmer surface air. Our trajectory should roughly follow a course northward, toward Garretson and the Palisades; by changing elevation, the pilot could steer slightly east or west.

A few blasts from the propane burner and the balloon stood erect, its smiling face toward the sky. “All my balloons have faces,” West says. “This one I call Sunny-Side-Up.” The crew anchored the gondola as West climbed in to take the controls, followed by Jessica, Justin and me. Another bellow from the burner heated the balloon’s interior — and our shoulders — and we lifted off. In moments the ground crew grew small. They climbed into the chase vehicle, a radio-equipped pickup truck, and began pursuit.

We soared to a quarter mile high, then floated in silence between the Beaver Creek Lutheran Church and Justin’s parents’ rural Brandon home. So far the ride was everything I had imagined. But suddenly it became more.

Justin dropped to one knee in the crowded basket and took Jessica’s hands. “Jessica,” he said, “we’ve had some pretty good times for a couple of years. I wonder if you’d spend the rest of your life with me.” He slipped a gleaming stone on her finger. West and I studied the cornfield passing below, giving the newly engaged couple a moment of what had to pass for privacy in the confines of a 3-by-4-foot wicker basket.

|

| Our writer's traveling companions, Justin Kuipers and Jessica Hudson, became engaged during the flight. |

A second first for me. The only other wedding proposal I’ve been privy to issued from my own lips 34 years ago, and I’m not sure what I said. For West, it was the second engagement flight of the week. The earlier marriage proposal came when a creative suitor floated with his prospective fiancée over Tuthill Park in Sioux Falls. Seventy-eight friends he’d bussed in for the occasion lay on the grass below, spelling out “Marry Me Amy.”

Our happy couple again became a part of the foursome as Interstate 90 came into view. Justin produced a cell phone and called his parents. “Look out your window,” he said. “You’ll see us sailing by.”

Kay West is no stranger to ballooning. She’s been flying for two decades, ever since as a single parent in California she started crewing for something fun and free to do on weekends. Sixteen years ago she married Mark West, now president of Aerostar International in Sioux Falls, the subsidiary of Raven Industries that until recently was the worldwide leader in building hot air balloons. “I didn’t come to Sioux Falls willingly,” she says. “Now you’d have to drag me kicking and screaming back to California.”

In 1994 Kay’s hobby became a business, when she founded Prairie Sky, one of two commercial ballooning operations in Sioux Falls. One of her balloons carries just two; Sunny-Side-Up has room for four. An hour-long flight consumes 12 to 14 gallons of propane in summer, less in winter, when less heat is required to lift the craft into colder skies. West takes about 100 people on commercial flights each year, and also provides flight instruction.

But this was no time for talking history, or the finer points of hot air flight. It was time to watch technique in action, and to appreciate the ride. Past the interstate, West pulled the cord that opens a vent in the balloon’s top; we dipped and skimmed across a cornfield in what she called “contour flying;” the altimeter read 20 feet.

At this elevation we caught the southeast breeze that carried us on a trajectory directly in line with Jessica’s parents’ home. As we approached, we ascended just enough to clear the mature ash trees that surround the two-story farmhouse, and yes, there was Jessica’s mother, waving in the front yard.

“She said ‘yes!’” Justin yells.

|

| Jessica's mother heard the news as the balloon flew over her house. |

“Congratulations!” comes the reply from the ground.

As we neared Palisades State Park, we drifted across a broad expanse of native prairie. We cruised over a coyote’s den. Pheasants cackled and flew from their overnight roosts. A magnificent buck glanced up as our shadow crossed. “That’s what I like most about flying,” West says, “the wildlife. You don’t see that from an airplane.” She is careful to avoid startling either wild animals or livestock.

We glided so low over a patch of cottonwoods south of the Garretson golf course that the pilot picked a leaf; she opened the top of the balloon again, and we dropped to skim the surface of a pond. Then she pulled a golf ball from a bag, hoping to score a hole-in-one. But the breeze had other ideas; we drifted past the green, and she saved the ball for another day.

West aimed for a grassy field behind the Nordstrom building on the south edge of Garretson, 11 miles from Beaver Creek. Three workers watched our descent and rushed over to hold the gondola as we climbed out.

“Be the first to congratulate the newly-engaged couple,” West says.

“That’s the way to do it,” a guy with “Tracy” stitched on his shirt tells Justin. “If she said ‘no,’ you could throw her out.”

Not likely.

Everybody helped to deflate and store the balloon. When it was tightly rolled, we stuffed it into its transport bag. “Now everybody turn your back to the bag and use your best assets,” West says. We sat in a circle on the edges and squeezed out remaining air.

Back at Beaver Creek, West offers the traditional balloonist’s prayer and champagne toast:

The winds have welcomed you with softness

The sun has kissed you with its warm hands

You have flown so high and so well

That God has joined you in his laughter

And set you gently back

Into the loving arms of Mother Earth

Following a flight with a sip of bubbly wine has been customary since Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier’s first hot air balloon flight in France in 1783. That experimental balloon was heated over a fire, and carried a sheep, a duck and a rooster for a low-altitude 2-mile cruise. When the balloon came down, frightened peasants came after it with pitchforks, so thenceforward the brothers carried a bottle of champagne as a peace offering to farmers on whose land they came down — or to consume should they be so fortunate as to land unobserved. Incidentally, the first man to fly the Montgolfier balloon was named Pilatre, from which we get “pilot.”

|

| A farmstead near Brandon, as seen from 1,000 feet overhead. |

West has flown at many events and places, including the Kentucky Derby, Germany, three South Dakota gubernatorial inaugurations and Devil’s Tower. But ask ballooners about their sport, and two cities come up. One is Albuquerque, New Mexico, where precision navigation is possible; the Sandia Mountains, in whose shadow Albuquerque lies, produce unusual air currents that make it possible to fly a broad circuit and land where you took off. Yet, in the history of ballooning, Sioux Falls is perhaps more important; it was in South Dakota that the sport of hot air ballooning really got off the ground.

South Dakota’s hot air balloon enthusiasts are a small club, including a dozen or so East River pilots in Sioux Falls, Irene, Yankton, Tyndall and Mitchell, and the state’s most active commercial pilot, Steve Bauer in Custer. The loose network maintains the South Dakota Balloon Association.

For eastern pilots, the event of the year is the Great Plains Hot Air Balloon Race in Sioux Falls. The key competition is the Hare and Hound Race. It’s not a race for speed, but for accuracy of navigation. The lead balloon, the “hare” takes off first, with the “hounds” in pursuit. The hare drops a cloth X; the hounds maneuver their balloons as close as possible and toss beanbags at the target.

Many consider Ed Yost, who co-founded Sioux Falls-based Raven Industries in 1956, as the father of modern ballooning. He died in 2007, but has not been forgotten thanks to his friend and fellow balloon enthusiast Russ Pohl.

A retired physicist and vice-president of Raven Industries who was first licensed as a balloon pilot in 1960, Pohl worked with Raven co-founder Yost on high altitude research projects for General Mills in the 1950s. Then the pair worked together at Raven to develop the hot air balloon for the Navy in the 1960s. Pohl served on the crew when Yost flew across the English Channel in 1963. Shortly thereafter, Yost almost completed the first balloon flight across the Atlantic Ocean, but unfavorable winds drove him back from the European shore.

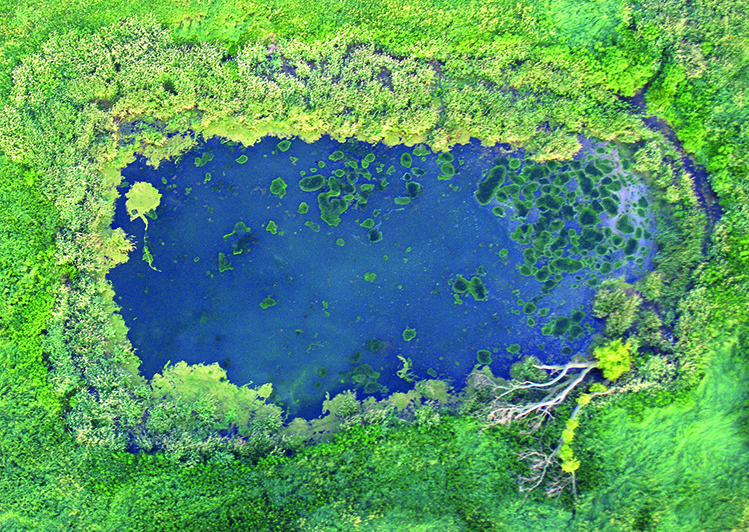

|

| A stock pond near the Garretson golf course. |

The modern hot air balloon evolved from a contract Raven received from the Office of Naval Research to build a reusable craft that could carry a man and payload to 10,000 feet and remain aloft for three hours. Yost first ascended from Bruning, Nebraska, in October 1960, in a propane-fueled envelope he had developed.

Over the years, Yost and Pohl experimented with gondolas made of plastic, fiberglass and aluminum, but finally concluded that the 18th-century French brothers had it right when they used wicker baskets. Their flexibility makes them safer and more comfortable in hard landings.

Besides Kay West, Sioux Falls’ other commercial pilot is Duane Waack, who calls his company Cloud Nine. Like West, he’s flown for 20 years and has been in business 16. He has also flown in Canada and Mexico, and over Mount Rushmore during the rededication ceremony in 1991.

Balloons are built to be functional, but they are beautiful as well; some are downright works of art. Wayne Hajek of Tyndall has two ordinary balloons, which he launches at various sites along the Missouri River. But he’s also part of Mitchell’s Corn Palace Balloon Club, which takes its specialty balloons to paying events around the country — balloons shaped like Uncle Sam, a lady with fruit on her head, Russian nesting dolls, the Marine Corps’ bulldog mascot and a witch on a broomstick.

Some balloon pilots fly on calm evenings, as well as mornings, taking off a couple hours before dark. But most avoid the volatile thermal activity that typically comes with hours of sunshine. Some, including commercial pilot Steve Bauer, fly only at sunrise. Bauer has flown passengers in the Black Hills since 1985. “A friend from Sioux Falls brought his balloon out and gave me my first ride, and I was hooked,” Bauer says. “It was kind of like sticking a needle in my arm. We’d land, and 10 cars would pull up and say ‘how can we get a ride?’” Thus, Black Hills Balloons was born.

Since then, Bauer, who grew up on a ranch near Wessington Springs, has flown all over the world. Re/Max officials hired him to fly their advertising balloon across the Caribbean to jump-start their real estate business. He’s flown in Central and South America, even over Europe’s Alps. Once he was flying for Ted Turner in Zimbabwe, and landed in a minefield. He helped Steve Fossett launch his balloon for the round-the-world flight in 2002.

“I’m an old boy now,” he says, “but in younger years I flew a lot of places where they said you couldn’t fly. That was all I needed to hear. Actually, the Black Hills is not the easiest place to fly. That’s why I don’t have a lot of competition.”

Bauer hosts a balloon rally in the Hills each year, the last weekend in July. “We have a nice get-together,” he says. “Albuquerque is all about money, but this is about flying and about getting old boys together.”

Bauer estimates there are perhaps 3,000 balloon pilots around the world. “But South Dakota had Raven,” he says, “so we probably have more pilots per capita than anywhere on Earth.”

| "Most pilots don't have to assemble their aircraft before they fly," said our pilot. The same is true of the landing. Everybody pitches in to deflate the balloon and squeeze out the air. Most outings finish with a traditional toast and some bubbly. |

In the Alps, Bauer piloted the richest of the rich, people who paid $14,000 for first-class accommodations and three days of flight. That’s a far cry from the style of Bauer’s Union County friend, pilot Kevin Kelly, for whom Bauer built an experimental balloon with $2,500 in nylon fabric, about a tenth the commercial cost of a comparable balloon.

Kelly and Bauer have flown together for years, not only in the Black Hills but also over Mexico, Guatemala and the Caribbean coast of Belize. But Kelly has only a private pilot license; he flies for sport, mostly over the hills and prairies of southeast South Dakota.

Kelly launches from neighbors’ pastures or harvested fields, and lands on county roads or whatever open places he can find. “The first rule of ballooning,” he says, “is never use power lines for brakes.” And neither does he carry champagne. “I find that a six-pack of Bud works better if you need to set your balloon down in somebody’s hayfield.”

Kelly says that he and Steve Bauer and the Black Hills gang have earned something of a “cowboy” reputation with some pilots, partly because Bauer’s summer rally lacks the strict rules of other balloon races. A rough landing once broke Kelly’s leg in three places, and another time he came down in a tree. But ballooning never loses its appeal for him. “It’s a perspective you don’t get any other way,” he says, “snuggled in a basket, drifting slowly.”

Vermillion artist Nancy Losacker, who has flown twice with Kelly, says the balloonist’s view of the textures and colors of corn and soybean fields changed her perception as a painter. “A hot air balloon is the only way I can see the world from the perspective of a bird,” she says.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2008 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments