The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

A Park of Peace

|

| Trinity Eco Prayer Park features species native to the Black Hills and surrounding area. |

Rapid City has 1,650 acres of parks, ranging from a long and wide swath of green along Rapid Creek to steep inclines up craggy Cowboy Hill (where a big “M” represents the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology campus) and specialty parks like Storybook Island and Dinosaur Park.

Every park has a story. Works Progress Administration laborers fashioned the dinosaurs from cement in the 1930s, and today the big reptiles oddly symbolize Rapid City like nothing else. The 1972 flood that killed 238 people led to development of the creekside greenway, representing both a memorial and a “never again” pledge to keep the floodplain free from residential construction. The “M” park (officially Hanson-Larsen Memorial) is a bit of wilderness in the midst of a city of 70,000, and features some 12 miles of hiking and biking trails with views of Black Elk Peak and the Needles.

Paddleboaters lazily float the waters of Canyon Lake Park, and Memorial Park near the Civic Center has a Veterans Memorial and a piece of the actual Berlin Wall. Sioux Park on the city’s west side is known for the William Noordermeer Formal Gardens while Wilson Park, a tiny greenspace in the West Boulevard Historic District, has formal gardens that were created as Japanese Gardens but modified after war was declared in 1941.

Such a rich and daunting history of parks didn’t deter Ken Steinken and his friends from undertaking a new project that embraces modern-day values of environmental sustainability and a livable downtown. The park, affiliated with Trinity Lutheran Church, isn’t city property but it welcomes the public — and city parks staff have been helpful in its development.

“There’s a sense of community here, and an interest in park-building within that community,” says Rapid City Parks and Recreation landscape designer Alex DeSmidt. “The Parks Department has such a wide focus, but groups come along that are focused on just one thing, like sports or in this case sustainability. Their work expands the park system even though they’re not under the jurisdiction of the city.”

Steinken knows there’s a lot more to park building than mowing a vacant lot and hanging out a welcome sign. There is hydrology to study, more than 100 plant species to consider, turf to haul and, of course, dollars to raise.

Trinity Eco Prayer Park occupies more than half an acre on St. Joseph Street, just east of Fifth Street. On the first day the mercury hit 70 in 2017, a handful of robins hopped across the grass, joggers and cyclists passed through, and a man reading a novel found a bench and stayed an hour. The park is, as a brochure promised, “a peaceful urban setting.”

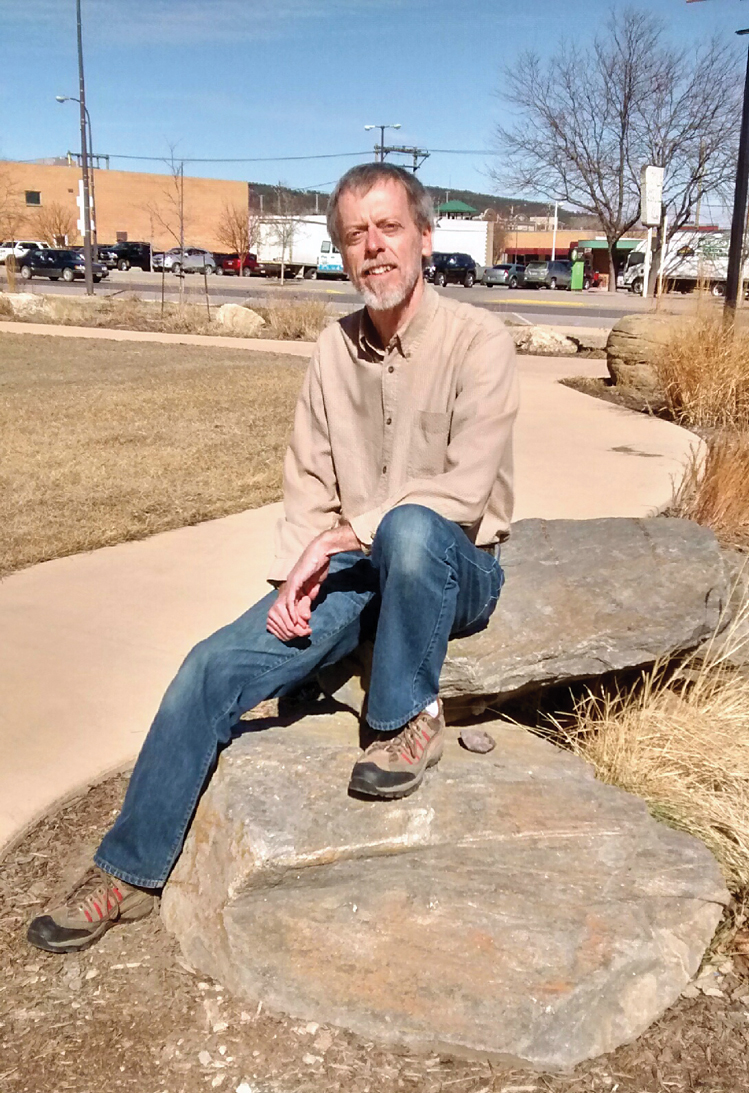

|

| Some Rapid Citians remember Ken Steinken as their former English teacher at Stevens High School. He is also a driving force behind the creation of the downtown park. |

Toward evening the skyline isn’t defined by a sunset silhouetting the Black Hills, but by the glow of big, classic neon signs on the nearby Hotel Alex Johnson and the South Dakota Stockgrowers’ building. Rather than scents of ponderosa pine or creekside vegetation, aromas of burgers and fries waft into the park from a Hardee’s next door. The spot feels like an extension of the neighborhood — an eclectic mix of buildings that include Trinity, single-story specialty shops, Racing Magpie gallery and studios, coffee shops, a dance studio, the Pennington County Courthouse, the Stockgrowers headquarters, and beautifully repurposed brick automotive sales and service structures. One such building, directly across the street from the park, is now a collaborative co-working space called The Garage that houses small businesses and nonprofits. Another, two minutes away by foot, is the new Black Hills bureau for South Dakota Public Broadcasting.

All of this, it’s important to stress, sits “east of Fifth.” For several years Rapid City has won acclaim for revitalizing its downtown, refurbishing historic buildings, attracting both retail and residents, and filling Main Street Square with year-round activity. But most of the rejuvenation happened west of high-traffic Fifth Street, and has only recently spread east of Fifth.

For a while it looked like the neighborhood’s redevelopment would be dominated by a 10-story combination retail/office tower, proposed for the very site where the park now lies. Members of Trinity Lutheran Church were concerned when they discovered that their church stood in the shadow of the tower. When the project stalled, they used a separate, long-established foundation to buy the land in 2005.

“We didn’t have any plans for the property,” recalls Steinken, a church member. “The foundation sprayed to keep weeds down. In fact, for two or three years after the spraying stopped, nothing grew.”

And so the half-acre lot sat bare, as far from park-like as imaginable. Churches can always use more parking, but there seemed to be an understanding that laying concrete would smother discussion of other possibilities. Once pavement goes down, it usually stays.

Gradually the idea of a public park emerged. “That put us on a kind of tightrope,” recalls Steinken. “The foundation that bought and still owns the property had gathered money over the years for benefitting the church.” While a park next door would certainly benefit Trinity, it would also welcome the wider community and, in fact, people unassociated with Trinity would vastly outnumber church-goers.

Pastor Wilbur Holz wasn’t surprised that his congregation thought that was fine. “A strong value this church has held for many years is its belief that that what God has given us should be used to bless others,” he says. “I think that describes the park.”

Even with that positive outlook, few could have guessed how quickly and seamlessly the park would fit as part of the neighborhood’s fabric.

Rapid City has a transient population. Inevitably the question was raised: Would homeless men and women stake out the park, sleep there and make it undesirable for parents and their kids? It hasn’t been a problem, partly because of the park’s open physical design, but also because of Trinity’s longtime relationship with the transient population. Members feed them (9,000 meals in 2016, reports Pastor Holz) and use that opportunity to form friendships.

|

| Native plants and creative space have drawn people of all ages to the park. |

“When you’ve worked with people and established a level of trust, they respect that,” Steinken says. “The park feels like an extension of the church to them.”

The park would also demonstrate good stewardship of the earth, a concept that intrigued Steinken and pulled him deeply into the project. He became the coordinator and, after ground was broken in 2014, found himself working with designers and builders and making hard decisions. “It was a weird situation,” he recalls, “because all I had was a little sourcebook about sustainable landscape construction. I’d ask myself, ‘Who am I to be doing this?’”

Describing Ken Steinken isn’t easy. He’s probably best known in Rapid City as a former Stevens High School English teacher (for two decades), but he’s also an author and former Rapid City Journal writer, works at the airport and has served as a ranger at Jewel Cave National Monument. It was there he noticed how many people love nature yet don’t really understand it, and that efforts to preserve nature sometimes keep the public at a distance.

Steinken and his wife, Penny, arrived in Rapid City in 1976. He came from suburban Chicago and she from the Boston area. Black Hills nature gripped them in ways that even the considerable charms of the Great Lakes and New England could not, and they built a good Rapid City life, raising two sons and a daughter. After retiring from teaching, Steinken found himself in the middle of the park project with its $440,000 price tag. Given his writing background it’s not surprising that Steinken can produce top-drawer press releases. He wrote one in November of 2011 and called a press conference announcing the park. Days later an anonymous contribution for $100,000 arrived. “The donor wrote a check, put it in an envelope, and just dropped it in the regular mail,” he remembers.

The team of church volunteers who came forward to help proved as valuable as the cash. Steinken found he could make calls and get friendly advice from the city Parks and Recreation Department, the U.S. Geological Survey and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“NRCS helped us with a plant species list, and information about how to plant those species,” Steinken says. Volunteers agreed the park wouldn’t be defined by Kentucky bluegrass. It would celebrate West River plant life, divided into four sections: Black Hills (switchgrass), shortgrass prairie (buffalo grass and grama), midgrass prairie (knee-high bluestem) and wetlands (prairie cordgrass).

“One of my advisors warned me that going that way would make it challenging to tell volunteers to go pull weeds,” Steinken says. “They have to know what’s supposed to be there.”

Cactus, it turns out, is supposed to be there. An area rancher offered buffalo grass from his pasture if volunteers came and carved out the sod. It was hard work, of course. “But in doing it that way, we got some cactus in the turf, too,” Steinken says.

Among the park’s signature concepts is modeling storm water gardening, drawing rainwater in rather than diverting it out, as urban development typically does. That form of gardening utilizes water naturally, prevents water pollution that occurs when the resource moves down street gutters, and lessens problem runoff during heavy rains. Steinken and his team thought long and hard about recommendations to install an irrigation sprinkler system, but eventually did. In 2015 plants were put in and the next year a water main broke, knocking the sprinklers out of commission for a long period in summer. The plant life did fine.

Modeling solar energy is another important mission. Solar-generated light illuminates the park after dark and solar collector panels provide power for some park maintenance, including charging a cordless weed-whacker. A big test will come this summer when volunteers hope to see a cordless electric mower operate on electricity generated in the park. The project’s Black Hills Energy bill is impressively low each month, and surplus electricity generated is sold back to the utility.

Trinity Eco Prayer Park opened in June of 2016. By that point it had already won a sustainability award from Rapid City. Summer barbecues draw hundreds, with music performed in a shelter on the park’s south end. There are also quiet times of prayer and reflection.

Steinken thinks the myriad activities in this little half acre all point to similar questions: “How do we relate to the planet? How do we relate to one another? It’s very much the same thing.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2017 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments