The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Modern Storyteller

|

| Downtown Rapid City has been artist Donald Montileaux's home base for more than 40 years. |

A pencil begins to scratch across a blank white sheet of paper. The noise is barely audible, but it’s there. Donald Montileaux is drawing Mickey Mouse. “It’s a stress reliever,” Montileaux says. “My other drawings take a lot of thinking, but Mickey, he just flows out of me.” He pauses for a moment. “You probably better not put that,” he says. “Walt Disney is gone, but his corporation is still around, and I might get in trouble.”

It seems doubtful that the multi-billion-dollar Walt Disney Corporation would kick up a fuss over a guy in South Dakota scrawling out a few Mickey Mouses just to keep his hands busy, especially if they knew the impact that one tiny cartoon character had on Montileaux’s life, and, in turn, the wider world of Native American art.

In his 71 years, Montileaux never earned a dime off a bootlegged Mickey Mouse. They’re drawn simply for the delight of his children and grandchildren, or because, after several decades of making art, his hands simply want to make more, even during an interview. His true passions are Indian warriors, horses and buffalo — not brown buffalo, but painted bright red, yellow or blue. His ledger art is an extension of the tribal tradition of painting or drawing on buffalo hides. Even casual observers can see the influences of his two main mentors: Herman Red Elk and the great Yanktonai artist Oscar Howe.

His paintings hang in homes and galleries around the world — and beyond. Within the last decade, Montileaux brought his art to the pages of children’s books, first as an illustrator and more recently as a storyteller. It was a long journey that required time, patience and ultimately acceptance from tribal elders as he sought to bring a much revered and protected Lakota tradition to a new medium.

And it all started at a kitchen table on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, when a father took his son into his lap and began teaching him how to draw Mickey Mouse.

***

Montileaux spent the first five years of his life in a small house in Kyle, the only child of Floyd and Clara Montileaux. “My mother and father only had eighth grade educations, and they had a hard time with life,” he says. “But they knew that the only way to really achieve anything was through education, and they wanted to give me a good education.”

The family moved to Rapid City, where Montileaux’s father took a job in a sawmill and his mother went to work as a dietician at St. John’s Hospital. Montileaux attended Catholic school through eighth grade. The course offerings did not include art, which led him to consider other career paths. “When I was in eighth grade, I wrote a little autobiography and said I wanted to become a priest. My dad was Lutheran, and my mom was Catholic. Dad said, ‘Maybe we need to broaden our son’s horizons a little bit.’”

They enrolled their son in public school, and an artistic fire that had been kindled on the reservation was reignited. Entertainment had been scarce in those days, so after the evening meal, while Montileaux’s mother washed dishes, he and his father grabbed a few comic books and sat at their kitchen table. “‘Let’s draw,’ he would say to me, and he’d help me. Mom was the judge. I drew a lot of Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy. That’s how he entertained me, but he also instilled a desire to become an artist.”

That desire blossomed at Rapid City High School. “In ninth grade, I was signing up for classes and one was industrial arts,” he says. “I just saw ‘arts’ and said, ‘Oh, I love that. Art.’ So I signed up. I walked in the door and here are all these nails and hammers and saws. I thought, ‘This is not what I wanted.’ So, I headed to the counselor’s office, and he said, ‘You want fine arts.’”

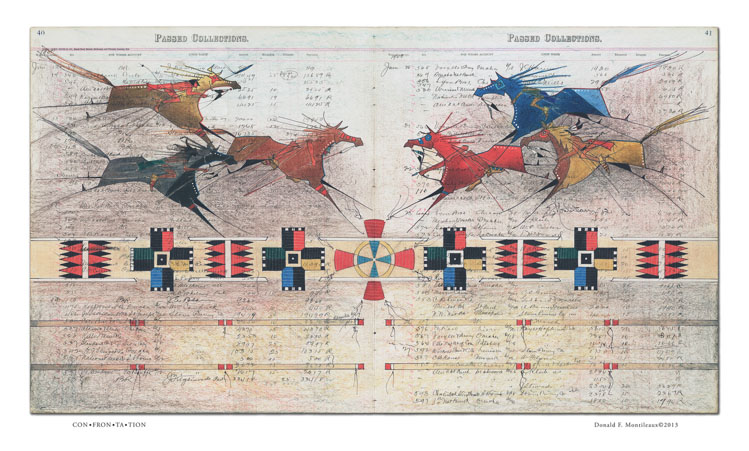

|

| "Confrontation" features Montileaux's brightly colored horses that seem to fly off the pages of a century-old ledger book. |

Montileaux explored ceramics, sculpture, drawing, painting — every artistic medium he could imagine. He was also drawn to the Sioux Indian Museum and Crafts Center in Halley Park, a facility administered by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board of the U.S. Department of the Interior. “I was too young to be in there alone so I would get kicked out. But I would continue to sneak in because they had this Native American wax figure called Oscar. I loved that guy.”

His precociousness aside, the museum curator, Ella Lebow, appreciated his persistence and, perhaps more importantly, recognized his artistic ability. In 1964, during his sophomore year, she recommended him for acceptance in a new summer art institute held at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion under the guidance of Oscar Howe.

The opportunity allowed Montileaux to learn from the two artists who became his lifelong friends and mentors — Howe and Herman Red Elk. Red Elk was a Yanktonai, born on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana in 1918. He became interested in art while recovering from tuberculosis at the Sioux Sanitarium in Rapid City. He enrolled in art courses at Black Hills State College in Spearfish and, through a program at the Sioux Indian Museum, studied traditional buffalo hide painting. Red Elk eventually joined the staff at the museum, where he remained until his death in 1986, and became one of the region’s most highly skilled hide painters.

Howe, born on the Crow Creek Reservation in 1915, is perhaps South Dakota’s most influential Native American artist. After studying at the Santa Fe Indian School, Howe abandoned the more traditional style he had learned there in favor of a more abstract method. His new paintings, marked by bright colors and pristine lines, helped push the boundaries of Native American art.

Howe taught at Pierre High School until 1957, when he was named artist in residence and professor of art at the University of South Dakota. He remained there until his retirement in 1980. In the early 1960s, he launched a summer art workshop designed to help students learn more about Native American art. Howe’s program lasted only a few years, but inspired the university’s current Oscar Howe Summer Art Institute, open to high school students in grades 10 through 12.

Red Elk and Montileaux traveled across the state together for Howe’s workshop in 1964 and again in 1965. “Oscar Howe was everything I wanted to be — an artist, a teacher and a family man,” Montileaux says. “He was a taskmaster and a professionalist. Before he even started drawing, he knew where those lines would go. He mentally had it in his head before he put it down on paper. So, for a 10th grader sitting in class — kind of wild and crazy and hard to stay attentive — he really had little time for me. But Herman was a mature adult, and he helped me get through that first two weeks with Oscar because Oscar was so regimented. But the second summer I went down there, I really became friends with Oscar because I had matured a little more and my drawings matured.”

Even though Montileaux had been a rough-around-the-edges sophomore in 1964, Howe could see that the young man had paid attention. Many of the techniques Howe had taught were becoming evident in Montileaux’s drawings. One night, Howe invited Montileaux and Red Elk to his home for dinner, where they met Howe’s wife, Heidi, and daughter, Inge Dawn.

“You don’t have a Lakota name,” Howe told him. “Montileaux is not a very Lakota name. So, Herman and I have been talking through the winter about a name for you. You’re like a little bird. You’re into everything. You fly all over, like a little yellow bird. So we’re going to give you the Lakota name Yellowbird. You’re going in a good direction, but you’re all over the place getting there.”

“I really feel proud of that,” Montileaux says. “Oscar and I developed a friendship. We became an extended family in the two weeks that I was there. After that, I could always call Oscar and talk to him. He was always available. After I became a successful artist and Oscar had passed away, Heidi would come to art shows and visit me. She would catch me up on the previous year. When she came into a show, everybody knew that for an hour don’t even come close to me, because that was Heidi’s and my time to talk.”

His stint in Vermillion helped Montileaux earn a full scholarship to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. After three years there, he earned another full scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island. But he soon discovered that the friendly and relaxed lifestyle to which he had grown accustomed in South Dakota and the Southwest did not exist on the East Coast. He came home and enrolled at Black Hills State College in Spearfish.

In 1970, he moved to the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation to teach elementary and junior high art. “I had wanted to be an art teacher, but I realized a teacher has not only the six or seven hours in the classroom, they devote 24 hours, seven days a week,” he says. “I had no time for my art.”

After three years at Cheyenne River, Montileaux moved back to Rapid City, hoping to find that ever elusive time to paint and draw.

***

That combination proved difficult to find. Montileaux needed a steady income, so he went to work at the Sioux Indian Museum, where he met his wife, Paulette. They were married in 1974.

In 1977, work was just finishing on the new Rushmore Plaza Civic Center. Montileaux took a job as a building foreman and was immediately thrust into preparations to host one of the most influential entertainers of all time. “I got hired two weeks before the building opened, and in less than a month we had Elvis Presley. It was just a buzz. Since I was the building foreman I got to go backstage when Elvis arrived. I was probably 5 feet from him, and I was just thrilled.”

|

| A buffalo hunt scene from "Tasunka: A Lakota Horse Legend." |

Montileaux eventually became the Civic Center’s event coordinator and finally its assistant manager. In the meantime, he’d created an art studio in his home. But the demands of a full-time job meant he still couldn’t give his art the time it needed. “What little time I had I would go down there and try to get inspired. I always thought the pieces I produced during that period were all unfinished. They just didn’t have that quality, that polish, that they could have had if I’d had more time.”

Still, a highlight of Montileaux’s career came in 1995 when one of his paintings was launched into space aboard the shuttle Endeavour. Montileaux was looking for ways to support a program called SKILL (Scientific Knowledge for Indian Learning and Leadership), offered through the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Richard Gowen, the school’s president, suggested Montileaux do a painting and sell prints, the proceeds from which would help fund the program.

Montileaux produced a Badlands scene with three young Native Americans gazing into the starry night sky. “I could not think of a title for this piece,” he says. “We were at the printer and he says, ‘I’m going to push the button, we need a title.’ Everyone was talking about what they saw in the painting. I said, ‘I don’t know … Looking Beyond One’s Self.’ He said, ‘Man, that’s great!’ and he hit the print button.”

An engineer working on the Endeavour’s upcoming mission offered to include the painting in the shuttle’s payload, in an effort to further publicize the fundraiser. It blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on the morning of March 2, 1995. Montileaux was not there. Instead, he stepped out into his front yard in Rapid City before sunrise that morning and, at the very minute Endeavour was scheduled to launch, he looked up at the stars — just like the subjects in his painting — knowing that his work was on an unprecedented journey into the universe.

Montileaux’s painting completed 262 orbits aboard Endeavour. Upon its return to earth, it was given to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Montileaux and others from the School of Mines traveled to the nation’s capital and presented President Bill Clinton with the No. 1 print.

Montileaux remained a weekend and evening artist during his 22-year career with the Civic Center. “We’d go to art shows on the weekends, and I’d always come back so inspired. Then we’d have to go to work the next day. I wished that I could be a full-time artist, and just do this.”

Finally, in 1999, at age 51 and with his three children grown, Montileaux and his wife began to consider that very possibility. “If you can make the house payment and put some food on the table, that’s all we really need,” Paulette told him. So Montileaux retired and, for the first time in his professional life, focused solely on art.

***

“I tried it and it just blossomed,” Montileaux says of the transition. One reason for his immediate success was his ledger art, a form in which scenes are drawn or painted on authentic ledger paper used by Indian agents or merchants during the late 1800s and early 1900s. “It had been dormant for so long that everyone was totally excited about it,” he says. “It was just me and about 10 other people doing it, nationwide. It was a very limited number of us.”

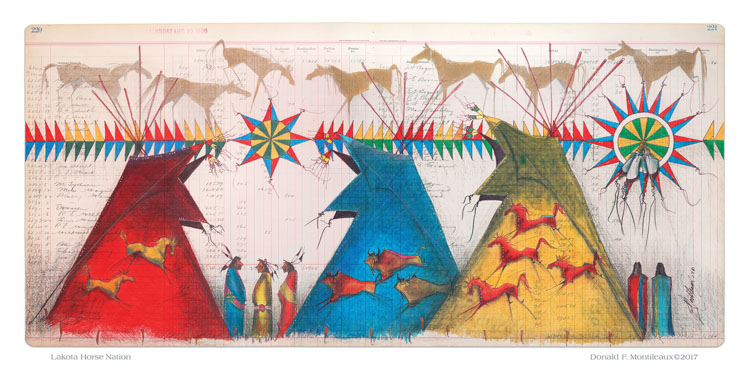

|

| "Lakota Horse Nation." |

Ledger art is an extension of the buffalo hide painting tradition at which Herman Red Elk excelled. “In the wintertime, Herman would tell me stories about his drawings and what they meant and their symbols. So I tried to be hide painter for a while, but he was a master. I researched and found that once the buffalo were annihilated from the plains, Indians had no way of holding on to their ceremonies and history because they didn’t have a written language. So they did ledger drawings.

“Hides were so hard to come by, and you had to have bone brushes and rabbit skin glue and earth pigments. It was dirty and hard to do. I picked up a colored pencil and laid it on a piece of ledger paper. All of my drawings that I used to do on those hides came alive on that piece of paper.”

While he collected awards for his ledger drawings, Montileaux’s paintings truly rounded into form, particularly the horses that have become his trademark. Once again, their origin lies with Herman Red Elk, and the stories he told while the two of them worked at the Sioux Indian Museum. Warriors used to survey the land for advantageous points from which to attack enemy tribes, Red Elk said, often a small rise or a hill. As they sprinted down the slope, warriors gave a small tug on their horses’ reins. A pouch of herbs slid into the mouths of their mounts, giving the animals a burst of energy. “He said the horses would just fly off the hill and into that enemy camp. As soon as he said the word ‘fly,’ my horses never galloped or loped again. My horses fly.”

The legs of a Montileaux horse are fully extended, sometimes inches and sometimes feet above the ground. Observers can almost hear them thundering across the prairie, just as Herman Red Elk said they did. It’s a technique that Montileaux has mastered. “Herman always told me that once you put that black paint onto a hide, you can’t make a mistake. You have to know where you are going with that line,” he says. “Herman used to close his eyes and draw his horses. And now today, I can close my eyes and I can draw my horses, too. It’s something that all artists have to do. We practice our craft so much that it becomes an extension of who we are.”

In Montileaux’s case, his art is very nearly an extension of the two great mentors who shaped his career. “The design that I put down is Herman. The brilliance of my color is probably Oscar showing through,” he says. “They’re not in any way close to Oscar’s presentation. But the training, how to mix colors, how to stretch my paper when I do a watercolor, he’s there. Every time I do something, Oscar’s there.”

***

In 2006, Montileaux’s art entered a new realm when he was asked to illustrate a children’s book. Tatanka and the Lakota People told the traditional Lakota story of how the holy man Tatanka turned himself into a buffalo to help the Pte Oyate (buffalo people) survive after their emergence from the underworld through Wind Cave in the Black Hills. The text was written and edited by a group of Lakota elders and scholars. Montileaux’s paintings were done in a two-dimensional style reminiscent of buffalo hide paintings.

Stories such as Tatanka were traditionally kept within the sacred realm of Lakota oral history. Montileaux recalls many evenings as a child on the Pine Ridge Reservation spent at his grandmother’s cabin, a tiny home with no electricity, listening to grandfathers and uncles tell stories. It was often the only form of available entertainment, and they commanded the room. “When my uncle Albert came, it was really kind of a gift,” Montileaux says. “We’d all gather around him and he’d just take us away, telling us about wild horses, and Indians and all these things that had happened. And we never once thought that he was keeping a tradition alive by being a storyteller. We just thought of him as Uncle Albert coming to tell us a story. I never thought of him as a traditional storyteller, but he was.”

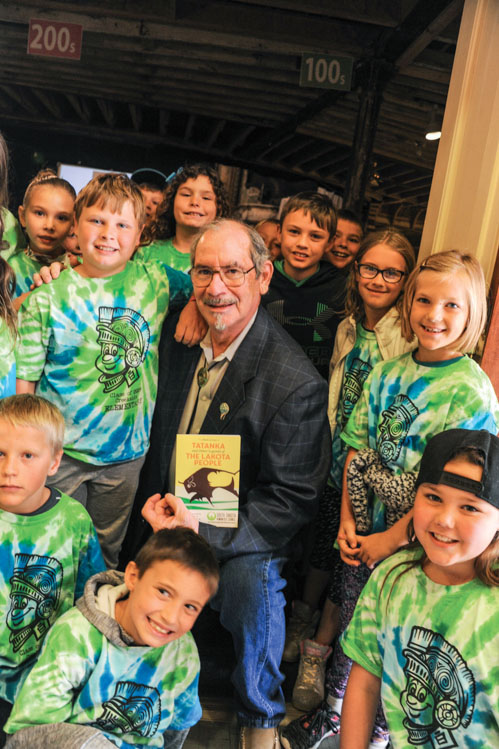

|

| Montileaux read stories to youth at the 2019 South Dakota Festival of Books in Deadwood. |

In 2014, Montileaux sought to bridge the divide between oral history and written stories once again, this time as both illustrator and storyteller. The idea came while visiting Alex White Plume, a Lakota elder perhaps best known for his battles against the federal government over the legalization of industrial hemp. “One night, Alex told stories. He’s a terrific storyteller,” Montileaux recalls. “He sat down and told this story and I thought, ‘My God, I’ve heard that story from my grandpas, grandmas and uncles throughout my childhood.’ It just struck a chord that I would like to write that story. And I listened to it — really listened to it — for the first time, because Alex was such a great storyteller.”

The story was about tasunka, the horse, and how these new creatures, once tamed, made the Lakota people rich and powerful. Montileaux worked on a few early drafts and shared them with White Plume, who remained unsure. “I really like what you’re doing here, but storytellers traditionally tell the story verbally,” White Plume told him. “We don’t write things down because we want people to listen to us when we tell stories. We want to make an impact on them.”

Montileaux understood White Plume’s concerns but explained that the Lakota people aren’t as centered as they once were. They live around the world and gathering for traditional storytelling sessions is much more difficult in the 21st century. They needed a new way to hear the stories that remain so important to their culture.

He went back to his Rapid City studio and finalized his text and ledger drawings. He asked Agnes Gay, the assistant archivist at Oglala Lakota College in Kyle, to provide the Lakota translation. After a rewrite that more sharply focused the story for children in second through fifth grade, Tasunka: A Lakota Horse Legend was published by the South Dakota Historical Society Press in 2014.

Montileaux brought the finished version to White Plume’s ranch near Manderson, unsure of what the elder would have to say. “His eyes lit up as he paged through it. He was pretty happy with everything. You could tell by his voice. He got done with the book and said, ‘Sit down. You got some time? I want to tell you a story about muskrat and skunk.’ So he told me the story, and then he said, ‘You know, I’ve thought about this and I think maybe you’re the one. Maybe you’re the person who does this for our tribe.’ And that was really an honor, because he accepted the fact that the book was good, and he gave me another story. But he also accepted the fact that we had to write things down to keep them alive.”

That began the latest chapter of Montileaux’s life, that of modern-day storyteller. The state historical society press published Muskrat and Skunk in 2017. This story explains the origins of the Lakota drum, once again with an accompanying translation from Agnes Gay.

Montileaux’s books reached a wider audience in 2019, when the press published all three stories in one volume called Tatanka and Other Legends of the Lakota People. As the South Dakota Humanities Council’s Young Readers One Book author, Montileaux spoke to students across the state leading up to his appearance at the South Dakota Festival of Books in Deadwood. More than 10,000 copies of Tatanka were distributed to second graders statewide.

***

Montileaux has established an artistic routine in retirement. His home studio contains everything he needs to do ledger drawings. He’s always on the lookout for ledger paper, particularly books that date between 1870 and 1930. They’re more plentiful than a person might think. They usually turn up at auction sales, or friends let him know if they see one in an antique store or elsewhere. “Every day I wake up, get my slippers on and come to my room,” he says. “I either pull out a piece that I’ve been working on or I start something new and different. Oscar Howe used to tell me, ‘Do every piece like it’s going to end up in the New York Museum of Fine Art, or even in the Louvre. Always have that attitude when you’re doing a piece, that it’s going to go far and it’s going to be there forever.’ I’ve always had that attitude.”

He keeps his painting supplies at a studio inside Prairie Edge, a store and gallery specializing in Native American arts and crafts in downtown Rapid City. He’s currently at work on another children’s book and a series of murals that will be installed inside South Dakota State University’s new American Indian Student Center sometime in 2020. Still, he wants to push his own artistic boundaries. “I really like to look at nature now. I’m trying to be that type of artist, like Renoir and Cézanne. You know how the colors of their fields look so bold and beautiful? I want to do that, but I want to incorporate some Lakota feeling into those pieces. Maybe a medicine wheel someplace.”

The pencil scratching begins to grow fainter. “He’s got some great ears, a little nose and his hand is coming up,” Montileaux says as he puts the finishing touches on Mickey Mouse. Donald Montileaux has received worldwide accolades and awards for his books and art, but for maybe just a moment, he’s back at that little kitchen table on the Pine Ridge Reservation where it all began.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2020 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments