The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Always on Our Minds

|

| A marker to Jack McCall stands in Yankton's Sacred Heart Cemetery, but does not mark his actual grave. That remains one of many mysteries that still surrounds the man who famously killed Wild Bill Hickok in 1876. |

A LEDGER BOOK is tucked away in the archives of the Mead Cultural Education Center, headquarters of the Yankton County Historical Society. Local historians have requested it often enough that museum staff have marked four pages with thin strips of white paper. “JAIL” is written in bold pencil across the top of one.

The book measures maybe 12 by 18 inches, contains some 600 pages and weighs about as much as a cinder block. Its first entry is dated Oct. 23, 1862 and is signed by George Pinney, the second United States Marshal in Dakota Territory. What follows are entries from each succeeding marshal — ranging from correspondence to reporting day-to-day activities of the office — ending on May 10, 1877.

Much of the reading is mundane, unless you’re captivated by expense reports, requests for 2-cent stamps, expense reports, applications for vacation time and expense reports. But there are a few needle-in-a-haystack nuggets that have consistently caught the attention of Yankton historians.

We first learned of the book’s existence from Bob Hanson, a tireless preserver of Yankton history until his death in 2018 and the man responsible for those bookmarks. Hanson was intensely interested in the story of Jack McCall, the man who killed Wild Bill Hickok in a Deadwood saloon, stood trial in Yankton and was executed just north of town. That sad and final chapter of McCall’s life spanned just seven months in 1876 and 1877, but its details have spawned nearly a century and a half of conjecture and speculation. What was McCall’s true motive? Was the crime a power play by territorial and federal politicians seeking a way to finally and firmly assert authority over the Black Hills? And where are Jack McCall’s remains today?

Hanson believed answers — or clues, at the very least — might be found in this book, hence his repeated visits to the Mead. But there’s another twist: two pages that would have contained official correspondence between Marshal J.H. Burdick and officials in Washington, D.C., between April 3 and 9, 1877 — just a month after McCall was hanged — are missing. To Hanson, they were akin to the 18 minutes of missing tape in the Watergate era.

Did the pages simply break free of their brittle binding and become lost among countless other documents? Or were they intentionally removed to forever obscure an incriminating piece of information? Most likely we’ll never know, but it hasn’t stopped people from asking questions. Nearly 150 years after his death, Jack McCall remains very much on many people’s minds.

***

WE KNOW VERY little about Jack McCall’s life prior to Aug. 2, 1876. Historians believe he was born in 1852 or 1853 in Louisville, Kentucky. He arrived in the Black Hills during the gold rush. One story contends that he entered the Hills as a wagon train driver for “Colorado Charlie” Utter, whose party also included the famed lawman Wild Bill Hickok, drawing the two figures of Western lore together for the first time.

|

| Jack McCall. |

Whether that actually happened is its own mystery, but we know McCall and Hickok were in Nuttall and Mann’s Saloon No. 10 in Deadwood on Aug. 2, 1876. Hickok was in the midst of a poker game when McCall approached him from behind, leveled a revolver at his head and pulled the trigger. Hickok died instantly and McCall fled down an alley, only to be apprehended later by a crowd of townspeople.

Since no established court had yet asserted jurisdiction over the Black Hills, crimes were often settled in miners’ courts in which a hastily assembled jury of locals convened to determine the fate of the accused. Such was the scene that awaited McCall the following afternoon in James McDaniels’ Deadwood Theatre. McCall claimed his deadly deed was vengeance because Wild Bill had murdered his brother in Kansas. The jury sympathized (or was swayed by a bribe of gold dust, as prosecutor George May surmised) and found McCall not guilty after a two-hour deliberation.

Believing he’d gotten away with murder, McCall fled for Laramie, Wyoming, where he seemed to relish in telling others that he was the man who had killed Wild Bill. Territorial authorities knew about the notorious crime and believed that McCall’s Deadwood trial held no legal standing. One day May, who had followed McCall to Laramie with Deputy U.S. Marshal Saint Andre Durand Balcombe, overheard McCall’s boasting. Balcombe arrested McCall on August 29 and escorted him to Yankton, Dakota Territory’s capital city.

As he awaited trial, McCall spent the next three months in jail. His cell mate was Jerry McCarty, who had been arrested for the murder of John Hinch in the Black Hills the day before the Hickok killing. The two hatched a daring and almost successful escape in early November. J.B. Robinson, the jailer, was preparing to lock them in their cells for the night when McCarty overpowered him and held him by the throat. McCall then beat him until he was nearly unconscious. They stole his keys, broke their shackles and were stepping out the door when they came face to face with Marshal Burdick and James Bennett, one of his assistants. As Yankton’s Daily Press and Dakotaian reported, in the wonderful language of 19th century journalism, “Marshal Burdick immediately comprehended the situation and placed the business end of his revolver in unpleasant proximity to the heads of the escaping murderers,” who were escorted without incident back to their cells.

McCall’s trial began on December 5, with Judge Peter Shannon presiding. Appointed to defend McCall were Oliver Shannon and William Henry Harrison Beadle, the man perhaps best known in Dakota history for his passionate defense of school lands. When Marshal Burdick escorted McCall into the courtroom, the Press and Dakotaian correspondent described him as “an evil looking man young in years but apparently old in sin.”

Townspeople filled the courtroom to hear testimony and closing arguments, which concluded after noon on December 6. George Shingle, Carl Mann and William Massie — all of whom were inside the No. 10 Saloon when Hickok was killed — identified McCall as the lone gunman. (According to legend, Massie still held the bullet that killed Hickok. After passing through Wild Bill’s head, it tore into Massie’s wrist where it remained until he died and was buried with it in 1910.)

The defense’s main argument was that Dakota Territory didn’t have jurisdiction over the Black Hills because it was still part of the Great Sioux Reservation, the boundaries of which had been established under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. The jury of 12 men disagreed and found McCall guilty. He was sentenced to hang on March 1. (Curiously, six months after the trial, the Press and Dakotaian reported on a new map drawn of the Black Hills region which placed Deadwood squarely in Dakota Territory. The map caused controversy among those who attempted to claim that Deadwood was actually part of Wyoming. Territorial leaders sought advice from Beadle, the defense lawyer who at one time was also a surveyor in Dakota. He said he was convinced that Deadwood was part of Dakota Territory.)

|

| Longtime Yankton historian Bob Hanson was a tireless researcher of the McCall case. |

McCall languished in jail for another two months. During his time in Yankton, his story kept changing. At one point he claimed he’d been drunk. Later, he said a man named John Varnes paid him to kill Hickok. Varnes held a grudge over a disputed poker game, he said.

A few days before the scheduled execution, the marshal’s office received a letter from a Mary McCall in Kentucky asking if the prisoner was her brother. “There was a young man of the name John McCall left here about six years ago, who has not been heard from for the last three years,” she wrote. “He has a father, mother, and three sisters living here in Louisville, who are very uneasy about him since they heard about the murder of Wild Bill.”

The letter seemed to unnerve McCall and may have prompted him to get rid of a document that could have shed more light on the Hickok murder. McCall had been preparing a written statement and asked the Press and Dakotaian to publish it after his death. But the night before the execution he destroyed it.

March 1 was a cold and drizzly day in Yankton. By 9:30 in the morning, a large crowd had gathered outside the jail at Fifth and Douglas. They watched as McCall climbed into a carriage with Father John Daxacher, a Catholic priest, and Phil Faulk, a Press and Dakotaian correspondent. “This mournful train, bearing its living victim to the grave, was preceded and followed by a long line of vehicles of every description, with hundreds on horseback and on foot, all leading north, out through Broadway,” Faulk wrote. “The rain which was falling had moistened the earth and deadened the sound of the carriage wheels. Not a word was spoken during the ride two miles to the school section north of the Catholic cemetery. McCall still continued to bear up bravely, even after the gallows loomed in full view.”

The wooden gallows had been constructed so that the throngs of people who attended could watch as McCall ascended the steps and Burdick placed the noose around his neck. But when the floor beneath his feet disappeared, McCall plunged into a boarded-up enclosure that prevented witnesses from watching the condemned man struggle to his final breath.

Twelve minutes later, two doctors pronounced McCall dead. His body was placed in a walnut coffin and buried very nearly on the spot. Jack McCall’s life ended, but his legend in Yankton was only beginning.

***

A WEEK BEFORE we examined the U.S. marshal’s ledger book, Jim Lane visited the Mead museum to do the same thing. Lane is a local historian who has doggedly researched the Hickok killing and McCall’s time in Yankton. “I’ve got a book written,” he says. “But it’s all in my head.”

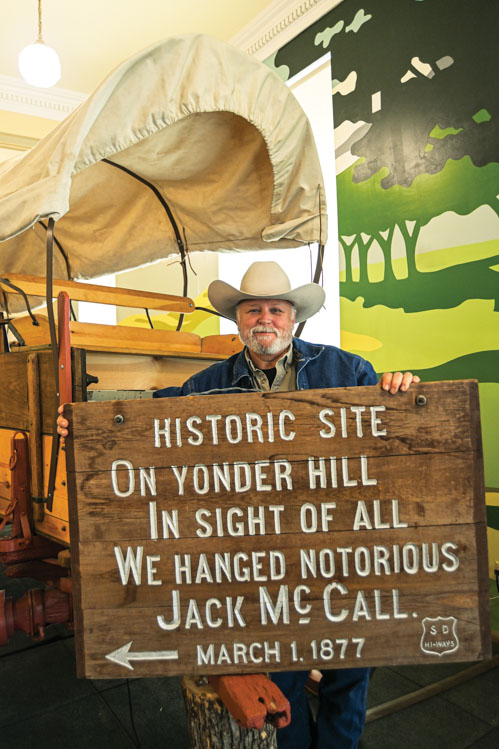

|

| A sign proclaiming Yankton's role in the saga of Jack McCall stood along Highway 81 before finding a home with the Yankton County Historical Society, headquartered at the Mead Cultural Heritage Center, where local historian Jim Lane researches McCall's time in Yankton. |

Lane’s interest in the ledger book centers more on the scruples of Marshal Burdick, the man in charge of the McCall execution, than any nefarious actions on the part of territorial politicians. “We don’t have a really good accounting on the McCall thing,” Lane says. “Burdick was a real reluctant guy. U.S. marshals weren’t Matt Dillon. They were political guys who took these jobs because it was a good way to make money on the frontier. He came under some fire and there was an investigation into his spending, right around that time frame.”

Hanson’s suspicions ran deeper. He believed there may have been a plan to kill Wild Bill Hickok so that federal marshals could swoop into the Hills, arrest the murderer and conduct the trial in territorial court, firmly establishing influence over the Black Hills. He turned to the book hoping to find clues. “Bob loved a good story, and he had a lot of fun with it. He kind of pushed the conspiracy theory,” Lane says. “When they hauled McCall back to Yankton, the territorial capital established legal authority over the Black Hills. That’s the case that does it. That’s when they say that if there’s going to be a trial out here, it’s going to be decided by Dakota Territory. Bob was a little bit right with the theory that they wanted this to happen. But I don’t think anyone assassinated Wild Bill Hickok for political means.”

There’s no smoking gun in the ledger book, either, though two of the bookmarked pages show that discussion of authority over the Black Hills was lively during the summer of 1876. On July 10, Marshal Burdick wrote to Attorney General Alphonso Taft regarding warrants that had been issued for the arrest of miners who brought whiskey into the Black Hills, still regarded as Indian Territory. Burdick’s position seems quite clear: “The Black Hills region as you are perhaps aware is located upon what is known as the Sioux Indian Reservation, within the limits of the Second Judicial District of this Territory, the Court being held at Yankton.”

Burdick said he had dispatched two deputies to arrest seven or eight men accused of bringing whiskey into the Hills, but that only one could be located. The others had escaped and probably could not be apprehended “by peaceable means.” He had requested military help from General Philip Sheridan, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, but given the obliteration of Lt. Col. George Custer and his 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn just two weeks earlier, he suspected no help would come.

“Any doubts which may have been raised in regard to the legality of the treaty under which the present Reservation was set apart I imagine has nothing to do with these cases. The United States Court here has never held that it is Indian Country,” Burdick wrote. “The people in the mining regions are firm in their belief that the Indians have no longer the right to prevent them through the action of the Government from occupying that section and working the mines. I state the fact without any reference to its correct basis.”

Still, he sought guidance. “The warrants in my hands are in proper shape for an offence clearly punishable under the Section referred to and are forced upon the indictments found by a qualified Grand Jury. I desire therefore in view of the peculiar circumstances which I have detailed to have your advice as to whether or not I shall proceed to execute them at all.”

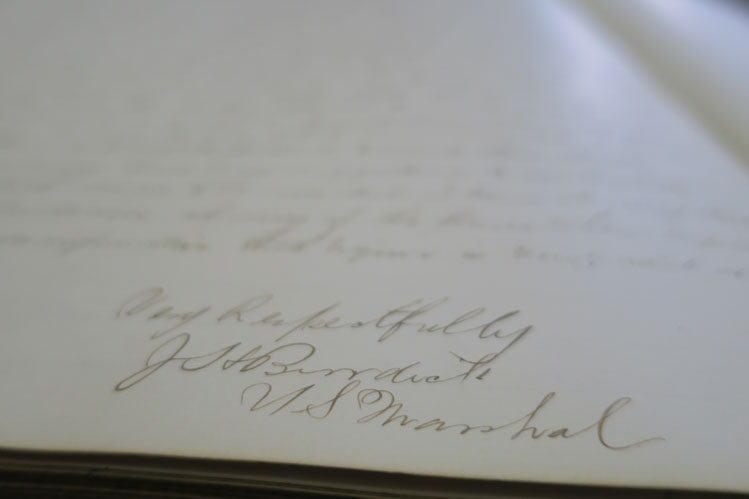

|

| The signature of U.S. Marshal J.H. Burdick, which appears many times in the historic ledger. |

Two weeks later, in another letter to the attorney general, Burdick reported that his request for military assistance had indeed been denied, but he also provided more details about his interest in the Black Hills. In February, he dispatched a deputy and a posse to the Black Hills to apprehend several men, one of whom was accused of a murder at the Standing Rock Indian Agency. The lawmen captured only one, who was tried, convicted and punished in the Yankton court. “The expenses of this posse were included in my accounts for the Spring Term of Court at this place and upon my accounts being presented to the Court for approval by law the Judge struck out all that portion of the account relating to the expense of the posse and refused to approve them. I referred the matter to the Hon. the 1st Comptroller and he refused to audit the account although he virtually admitted its legality saying he would not look into an account which the Judge refused to approve.” Clearly, questions remained regarding what the marshal could and couldn’t do in the Black Hills.

Another marked page helps us to find the tangible reminders of McCall’s brief existence in Yankton. In September of 1865, Marshal L.H. Litchfield wrote to Secretary of the Interior James Harlan to ask again for a jail. He referenced a previous letter in which the secretary claimed that no request for jail space had ever been received. But Litchfield was insistent. “At the time I made the request I stated distinctly that the United States had no rooms suitable for the confinement of prisoners. There never has been in this Territory any rooms used for this purpose,” Litchfield said. “The Judges and myself could not complain of the unsuitableness of rooms, but we did complain that there were no rooms, and that prisoners had to be confined at a military post or in a county jail of Iowa, either of which is more than sixty five miles distant from here.

“I wish the Department to distinctly understand that no rooms of any description have ever been provided or rented in this Territory for the safe keeping of prisoners. But there is great necessity for such rooms.”

Perhaps Litchfield’s entreaties resulted in construction of the federal jail on Linn Street, the facility in which McCall spent at least some time in custody. A tidy brown house sits on the lot today, just a block west of Broadway Avenue, the main north/south thoroughfare through Yankton.

McCall was also held in the relatively new county courthouse and jail, a large brick structure at the corner of Fifth and Douglas. Later, it was a lodge for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows but has since been converted into apartments. Its owner reported that before renovations, sections of bars could still be seen in the basement.

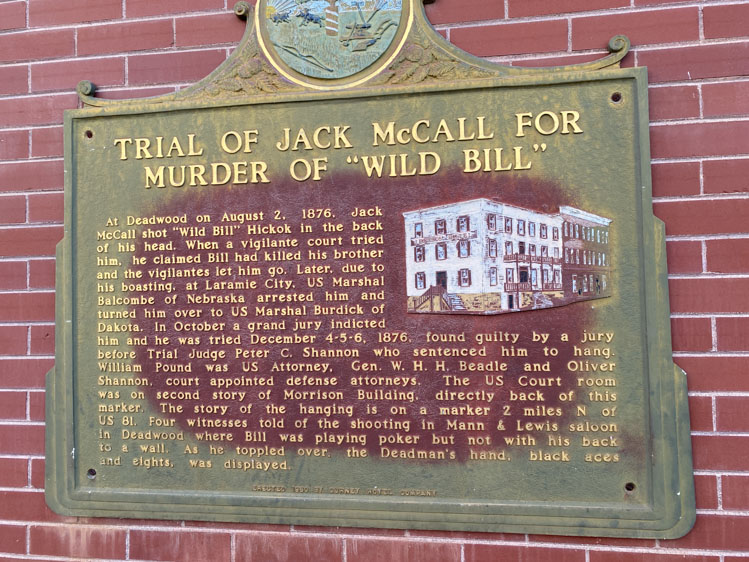

The building where McCall stood trial was part of the St. Charles Hotel, built in 1870 at Third and Capital. A portion of the building at the very corner of the intersection was rebuilt in 1891, but wings to the west and north — which included a courtroom where the trial occurred — remain. It also has been converted into apartments. A historic marker was placed on the east exterior wall along Capital Street in 1960. Its language, describing the courtroom’s location “directly back of this marker,” is to be interpreted literally.

|

| Jack McCall stood trial on the second floor of the brick building at Third and Capital in downtown Yankton. The location is prominently marked. |

A second marker stands at the intersection of 31st and Broadway near Yankton’s soccer fields. In 1877 this was the place where hundreds of people watched Jack McCall hang. The area has been graded and built upon several times through the years as Yankton gradually expanded to the north, but Lane believes the gallows were built somewhere in today’s Highway 81 right of way near the southbound lanes.

Perhaps the most intriguing mystery surrounding McCall is the location of his gravesite. Four years after the hanging, construction began on the Dakota Hospital for the Insane. McCall’s body, along with several others that had been buried in the pioneer cemetery, had to be relocated. When they opened McCall’s coffin, onlookers were surprised to discover that he’d been buried with the noose still tied around his neck.

McCall was moved to the Catholic cemetery, adjacent to the city cemetery. Over the years, his gravesite became a tourist attraction, much to the chagrin of the city’s Catholic leaders. Local historians say that in the 1930s, Father Lawrence Link, who served Yankton’s Sacred Heart Church from 1895 until his death in 1946, supervised a third relocation of McCall’s remains. This time, he was buried in an unmarked grave in Sacred Heart Cemetery along Douglas Avenue, where he lies today.

A headstone claims to mark McCall’s grave, but in fact it threatens to eventually muddy the historical waters. It was placed in 2017 when the Amazon television show Fireball Run passed through Yankton. The premise involved teams of people traveling through communities on missions or adventures that allowed them to see and experience unique aspects of each city. When the city’s Catholic priests balked at placing a headstone at the actual gravesite, a marker was set inside the adjacent city cemetery instead. The inscription on the stone reads, “Here lies Jack McCall,” but it was placed on a spot where the legendary outlaw definitely does not lie.

The real location of the gravesite is a closely guarded secret. Local legend says that no more than a few people at a time know exactly where it is. Bob Hanson was one of those people, and he remained coy about it, even among his closest family members. “Before he died, he told me where McCall is buried, but I think it was to throw me off the trail,” says Sarah Hanson-Pareek, Hanson’s daughter and a library archivist at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. “I’m not sure if I got the true account.”

A true accounting of anything surrounding Jack McCall would be difficult to put together. “There are so many trails that lead off this story that just haven’t been followed,” Lane says. “Everyone’s done Hickok and Calamity Jane to death. Nobody really looks at McCall because there hasn’t been much there. But we should be hopeful that the current interest in genealogy and clues such as the Mary McCall letter might lead to new discoveries.” Easier access to materials online, such as digitized newspapers and ancestry websites, could help further investigations.

Then there’s the ledger book. Is the paucity of information simply due to the time that has passed, or is it at least partly intentional? What of missing pages 509 and 510? Lane is convinced. “I don’t see any evidence of anyone cutting pages out,” he says. “It just ended before it got to any of the stuff that we were interested in.”

With Jack McCall, it seems there will always be more questions than answers.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2021 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments