The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Finding Frank Ashford

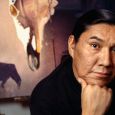

|

| Aberdeen's Troy McQuillen became fascinated by the work of Frank Ashford at the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library, which owns several oil paintings by the Brown County artist. McQuillen is searching the world for more of Ashford's work, and hopes to answer at least some of the questions that remain about the quiet painter from Stratford. Photo by Stephanie Staab |

There’s a painting in the Dacotah Prairie Museum in Aberdeen of a woman wearing a salmon-colored sleeveless dress, a floral print shawl, her left hand drawn to her chest as she gazes off the canvas directly at the viewer. Twelve years ago, when South Dakota Magazine assembled a list of paintings every South Dakotan should see, the late John Day — a widely respected art scholar and then curator of the Oscar Howe Gallery at the University of South Dakota — included Woman with a Shawl on his list of the 10 best paintings ever produced by a South Dakotan.

We know nothing about the identity of the woman and, for many years, very little about the man who painted her, even though Frank Ashford was considered among the best American artists of his time. Ashford grew up near Stratford and traveled the world, painting portraits of governors, Supreme Court justices, a U.S. president and the First Lady and other members of high society. He painted in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Seattle, Paris and the banks of the James River in Brown County.

Ashford likely produced hundreds of paintings, many of which have been lost since his death in 1960, several years before a young Troy McQuillen began noticing the few Ashfords hanging in Aberdeen’s public library. Decades later, those childhood memories sparked a quest to find as many of the old artist’s paintings as he can, and maybe learn something about the man along the way. Among his early discoveries? He’s not the first Aberdonian to go looking for Frank Ashford.

***

Elderkin Potter Ashford was a Civil War veteran, serving with the 23rd Iowa Volunteers at Milliken’s Bend, Vicksburg and Mobile, among other prominent battles. He moved his family to a homestead in Rondell Township, southeast of Aberdeen along the James River near Stratford in 1893. The Ashfords included his wife Cassandra, who suffered from arthritis and spent many years confined to a wheelchair, daughters Grace and Helen, and sons Ward, Fred and Frank, who was born in 1878.

The elder Ashford never lost his sense of patriotism. He hosted a grand celebration at his homestead every Memorial Day. Hundreds of people met to decorate graves at nearby Oakwood Cemetery, then heard speeches delivered from the front porch of the Ashford home. Many locals believed that Frank’s interest in painting portraits of politicians stemmed from those annual gatherings.

Just before he turned 18, Frank left Brown County for the Chicago Art Institute, where he studied drawing under Frederick Frier and John Vanderpoel. After three years in Chicago, he spent a year at the Pennsylvania Art Institute in Philadelphia and another year at the New York School of Art, studying in both places under William Merritt Chase, an Impressionist painter perhaps best known for his portraits.

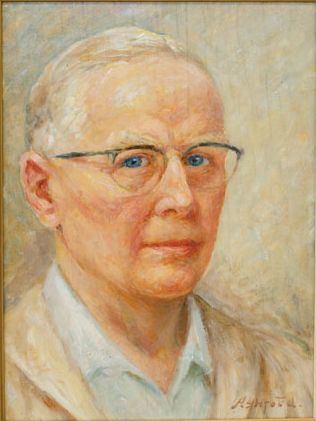

|

| Ashford's self-portrait. |

Following his studies, Ashford established a studio in Paris, where he painted for seven years. He visited home in April of 1912, sailing on a French ship called the Bretagne, which passed through the same North Atlantic iceberg field that doomed the Titanic later that same day. “We passengers aboard could not grasp the full purport of the tragedy,” Ashford told the Aberdeen Weekly News when he arrived in town in May. “It was so overwhelming, and many did not believe it until we reached New York.”

As World War I embroiled Europe, Ashford returned to the United States permanently in 1914. He spent time painting in New York, Minneapolis and Seattle before settling down in South Dakota sometime in the 1920s. A Sioux Falls Argus Leader story from that decade referred to Ashford as, “such a simple, common, everyday person, friendly and unassuming, and not at all what one would think of an artist who had lived in Paris.”

Ashford was briefly married around that time to a model he’d met in New York named Marjorie Rickel, but they divorced in 1929. Locals around Stratford believed the marriage ended because Rickel could not get accustomed to South Dakota’s rural lifestyle and was bitter about supporting her husband, who excelled in making art but struggled with financial management.

Ashford painted several prominent politicians and judges beginning in the 1920s, including Louis Brandeis, chief justice of the New York Supreme Court. He painted three South Dakota Supreme Court justices, as well as governors Andrew Lee and Charles Herreid. He later painted governors Leslie Jensen, Sigurd Anderson and Joe Foss twice, once as a politician and again as a World War II aviator.

His work was attracting an audience. In the late 1920s, he sold 11 oil paintings to be placed around the campus of the Dakota Hospital for the Insane in Yankton (today the Human Services Center). The purchase was an extension of the efforts of Dr. Leonard Mead, the hospital’s superintendent from 1891 to 1899 and again from 1901 until his death in 1920. Mead believed that creating a more welcoming environment through art and architectural beauty would help patients recover. He began an art collection with several watercolors in 1906, and the Ashford oils added to the campus décor.

Perhaps Ashford’s biggest professional achievement came in 1927 when he learned that President Calvin Coolidge planned to spend the summer in the Black Hills. He asked his friend, state historian Doane Robinson, if it would be possible to have Coolidge and his wife Grace sit for portraits. The two exchanged letters, and eventually Sen. Peter Norbeck — among the architects of the president’s vacation to South Dakota — was added. The flurry of correspondence resulted in a sitting at the Custer State Park Game Lodge in July.

Remarkably, Ashford had the Coolidge paintings nearly finished by mid-August. He often said that he only needed to sit with a subject for three to five hours and could finish a nearly life-size portrait in about 10 days. Ashford produced two paintings each of the president and the First Lady. A portrait of Coolidge seated and wearing a light-colored suit and another of Grace Coolidge in a green dress hang in the lodge’s lobby. Another showing the president wearing a headdress and Grace in a red dress hang in the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library and Museum at Forbes College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

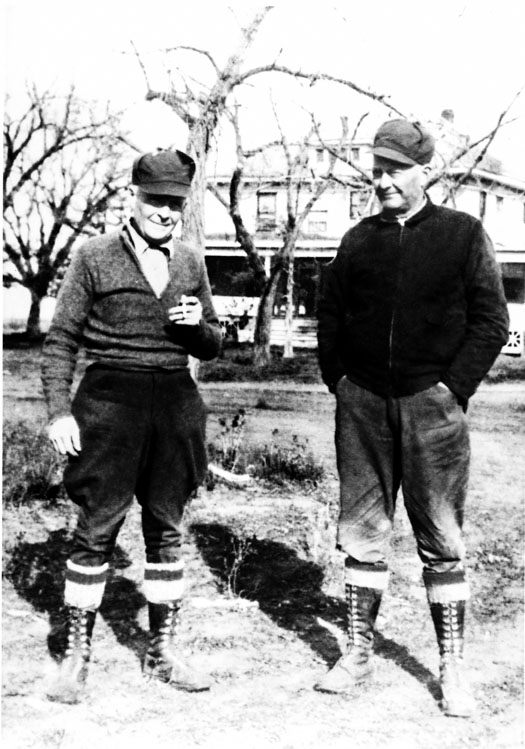

|

| Frank and his brother Fred (right), pictured in about 1940, were among five siblings who lived on the Ashford family's Brown County homestead. |

Ashford was happy with his Coolidge work. “The portrait of Coolidge, I think, is one of my best and it pleased him very much,” he wrote to a friend in Seattle. “Mr. Coolidge remarked that he thought it was the most satisfactory portrait that had been painted of him, which I considered a high compliment, as he had been painted by several noted artists.”

The following year, Ashford was commissioned to paint a portrait of William Henry Harrison Beadle, known in South Dakota as the savior of school lands because of his foresight to preserve two sections in each township for schools at a time when speculators gobbled up land at tremendously low prices. To commemorate the 90th anniversary of Beadle’s birth, the Young Citizens League and E.C. Clifford, the state superintendent of schools, created a plan to place Beadle’s picture in every South Dakota school. Ashford would paint the oil portrait and hundreds of prints would be made.

Ashford reportedly painted a portrait based on a photograph of Beadle, but the whereabouts of the original art and prints is a mystery.

Painting opportunities were slim during the Depression, World War II and the postwar years. Growing older and feeling lonely, he went to live with his brother and sister-in-law, Ward and Violet Ashford, in Salem, Oregon, in 1948. He became re-energized by the beauty of the Willamette Valley and painted several landscapes around the Ashfords’ farm. He also opened a studio, where he painted until returning to Aberdeen in 1956.

Ashford moved into the Boyd Apartments on the second floor of the Malchow Building downtown and settled into a routine. He met with locals for coffee and meals, and every afternoon stopped at Plymouth Clothing to visit a group of downtown business owners and friends. When he didn’t arrive on Nov. 21, 1960, they went to his apartment where they found him dead of a heart attack. Ashford was 82.

***

This story would be considerably shorter if not for the tireless work of Frances “Peg” Lamont. She spent more than a year researching Ashford for a paper presented at Augustana University’s annual Dakota Conference in 1990 and uncovered many of the aforementioned details about his life and career. Lamont served seven terms in the state senate from Aberdeen and was a longtime advocate for historic preservation, women, senior citizens and mental health. She was a founding member of the Dacotah Prairie Museum and Historic South Dakota, helped launch the Northeastern Mental Health Center and was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the Federal Council on Aging, where she served three terms. She remained active in several endeavors until her death in 2008 at age 94.

|

| McQuillen discovered Ashford's Yellow Chrysanthemums at Pomona College in California. |

Lamont was visiting the Black Hills with her parents, Fred and Frances Stiles, in the 1930s when she first saw the 1927 Ashford portraits of Calvin and Grace Coolidge hanging at the Custer State Park Game Lodge. It served as her introduction to Ashford, who was never far from her mind, even as she left South Dakota to attend the University of Wisconsin at Madison and found work as a researcher and copy writer for the Ladies’ Home Journal and McCall’s in New York City.

She and her husband William Lamont, a Harvard-educated fellow South Dakotan, made their home in Aberdeen after their marriage in 1937. The Lamonts became entrenched in life in the Hub City while Ashford painted in and around Aberdeen and Oregon. When he died in 1960, Ashford left 23 paintings in his apartment and the family home near Stratford. Local attorneys Hugh Agor and Douglas Bantz became the executors of Ashford’s estate and struggled to sell the art. They bought several paintings themselves and donated others to the Alexander Mitchell Public Library (today the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library) and the Dacotah Prairie Museum. Lamont ensured that the two Coolidge portraits made their way to Massachusetts. Others have simply disappeared.

Nearly 30 years later, with Ashford fading into obscurity, Lamont began to wonder what became of his paintings. She launched a worldwide search and tried to learn as much about Ashford as could be discovered. “For years, bits and pieces of Frank Ashford’s life had delighted me,” Lamont wrote. “Finally came the time to write about him, but libraries, art schools and records were scarce. The search for Ashford paintings has all the elements of untangling a mystery.” Fortunately, there were still several families in and around Stratford who shared their memories of Ashford. Those interviews, along with a smattering of publications and newspaper articles, revealed a prolific and energetic artist. “It seemed that wherever he stopped, even briefly, and found an interesting client, he established a studio and proceeded to paint with vigor and enthusiasm, turning out untold hundreds of artworks.”

Lamont successfully located several of those paintings, and today McQuillen is continuing her work. He is the owner of McQuillen Creative Group, an advertising and marketing business located across the street from the building where Ashford lived his final years. He also publishes Aberdeen Magazine and wrote a story about his Ashford quest in early 2018. “I used to go to the Alexander Mitchell Library a lot when I was a kid, and his paintings were all over,” McQuillen says. “The images were just burned into my brain. Then as an adult, I started a magazine and got on the library board and really started to wonder what these paintings were about. I learned about his national and international reputation for being a pretty good artist.”

The internet makes searching a little easier, with paintings occasionally showing up on online auction sites such as eBay (a seller in Portland, Oregon, is currently offering an Ashford portrait of a boy in a cowboy outfit for $795). But there remains a lot of sifting through historical paperwork. For example, a newspaper article from the 1950s mentioned that a couple donated two Ashford paintings to Pomona College in Claremont, California on behalf of a friend. McQuillen contacted the school, which had no record of it. But staff at the college’s Benton Museum of Art searched the archives and found a still life called Yellow Chrysanthemums, dated 1916 and signed “Ashford.” The second painting remains lost.

|

| Woman with a Shawl, among Ashford's most famous portraits, hangs at Aberdeen's Dacotah Prairie Museum. |

Another elusive painting is The Three Sisters, a critically acclaimed work that Ashford exhibited in Paris in 1912. Records indicate that he kept the painting, and a photograph from an exhibition in Aberdeen during the late 1950s shows it hanging on the wall. But The Three Sisters was not listed among the paintings in Ashford’s estate when he died.

Other works have disappeared even more recently. During Lamont’s search 30 years ago, she documented only five of the 11 paintings that were sold to the Human Services Center in Yankton. When McQuillen inquired in early 2021, he found just three: Modern Madonna, Lincoln the Lawyer and a portrait of former administrator George Sheldon Adams.

For South Dakotans wishing to see Ashford’s work firsthand, a trip to Aberdeen in the best bet. The Dacotah Prairie Museum owns a winter landscape and six portraits: Marjorie (his wife), Fred Hatterschiedt and Ole Swanson (both local businessmen), Woman with a Green Headband, Woman with Coral Necklace and Woman with a Shawl. The museum also has Ashford’s palette, easel, his lamp for portrait painting and his wooden traveling painting case, still filled with supplies.

The K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library has Woman in Pink; Abraham Lincoln (based on a rare ambrotype photograph that he owned taken of Lincoln in 1858 and similar to the Lincoln portrait at the Human Services Center); Governor Joe Foss, The Aviator and War Hero; Woman at Piano; and Ashford’s self-portrait, among other works.

McQuillen has also launched a website, which includes photographs of nearly 40 paintings that he has rediscovered, with more to come. “My goal here is that if people or antique stores have paintings by him, then at least they would know who he is and what they have,” he says.

It’s a modest goal to honor an equally modest man, who should always be remembered in South Dakota’s art world and beyond.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2021 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments