The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Gator Shows

|

| Ryan Comer deals with an ornery gator in the show arena at Reptile Gardens. |

Rapid City is a thousand miles from the natural habitats of giant lizards, but Matt Plank’s boyhood dream was to work with alligators and snakes. Fortunately, one of the world’s largest collections was right down the highway.

Reptiles were “always a passion,” Plank says. “I always watched Animal Planet, was always catching garter snakes, frogs and toads. It seems to be luck that I grew up next to this,” he said as he walked through the Sky Dome of Reptile Gardens.

Plank got a job in the cafe at the expansive attraction in 2002, worked there seasonally while earning a biology degree in 2010 from Arizona State University and joined the permanent staff in 2013. He is now assistant curator and show coordinator, overseeing the educational performances for summer visitors.

Now he works alongside Head Curator Terry Phillip, who found his way to Reptile Gardens after managing a pet store in Colorado and focusing on “reptiles, dinosaurs, girls and business, not necessarily in that order,” he says with a smile. “I was not so successful at most of them.”

Phillip moved to the Black Hills, where he had relatives, and started doing alligator shows at Reptile Gardens in 1997. Today he is among the country’s top authorities on crocs, venomous snakes and other reptiles.

American alligators are one of the great success stories of conservation. Once endangered, they could have easily been hunted to extinction when people moved into their habitats. But alligators adapted and responded to preservation efforts; today they are thriving in the southern United States. Most of the gators at Reptile Gardens are captured in places like eastern Texas and South Carolina where they have become a nuisance in populated areas.

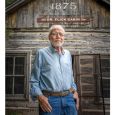

|

| Rapid City native Matt Plank found a calling among the large reptiles that live just outside his hometown. |

“Gator wrestling” has been a staple at reptile zoos for decades, however the shows at Reptile Gardens do not actually include grappling. At Rapid City, the entertainers seek to demonstrate the agility and strength of their alligators and crocodiles.

The shows took a two-year break due to the COVID-19 pandemic but returned in 2022. Phillip said the revived shows brought together an inexperienced staff and animals that weren’t used to the handling, a hazardous combination. Even though the staff and the animals grow accustomed to each other, there’s reason for caution around them. “We aim for the art of perfection,” Phillip says. “You can’t make mistakes. The biggest problem is complacency. You don’t want that with dangerous animals.”

“You get hit by one of these gators you’ll feel it,” he said. Right on cue, an alligator that was being moved to a different enclosure swung his head and smashed the taillight on a pickup.

Accidents and injuries do occur. “I made it my first year without getting bit,” Plank says, but admitted he has been injured several times. “Now I do everything I can not to get on a gator,” he chuckled. “When it’s exciting it means something’s not going well.”

Showing scars along his arm and fingers, Plank recalled a bite that required 17 stitches. “I remember his mouth right here,” he says, clamping one hand onto the scarred one. Reptile Gardens Public Relations Director Johnny Brockelsby — son of Earl Brockelsby, who founded the popular Black Hills attraction in 1937 — recalls hearing on the staff walkie-talkie that a manager was needed at the alligator arena immediately.

“‘Immediately’ means there is something serious,” Brockelsby says, pointing out that he’s not at his best in emergency situations. “When I got there, Matt was just sitting on the gator like normal and I asked what was wrong.”

“Johnny, my hand is in his mouth,” Plank replied.

|

| Terry Phillip has trained numerous animal wranglers and emergency personnel on handling dangerous reptiles. |

“Matt had sweat streaming down the side of his face, so I gave the gator a light tap on the nose, but nothing happened,” Brockelsby says. After another smack on the nose, with Plank pushing down as hard as he could, he got the animal to open his jaws.

“Then he says, ‘Johnny, should I finish the show?’” Brockelsby laughs. “I said, ‘No, I’m taking you to the emergency room.’ Luckily his fingers were between the teeth, or it could have been a lot worse.”

Phillip calls the incident the “most significant in my time here,” and Plank agrees. “It’s the close calls that scare you the most,” he adds.

Recognized as one of the largest collections of reptiles in the world, Reptile Gardens is also a place where other people seek advice. “We get questions from all over the planet,” Plank says. The staff also keep one of the largest and most diverse supplies of antivenom in the world.

Phillip is proud of the training he’s helped provide for area medical technicians, law enforcement officers, EMTs and first responders. He has offered staff training for other zoos and animal parks. He recognizes that his expertise is unique and helpful in certain situations. “Anytime, anywhere, for any reason for law enforcement and emergency personnel,” he says. He has also been part of several confiscations of illegal reptile collections around the country, some of which were added to the displays at Reptile Gardens.

Plank loves his job and wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. “Sometimes I’m jealous of the Florida parks because of the weather,” he says. “But there’s something about this place.”

Not even a gator bite will change his mind.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments