The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Larger Than Life

|

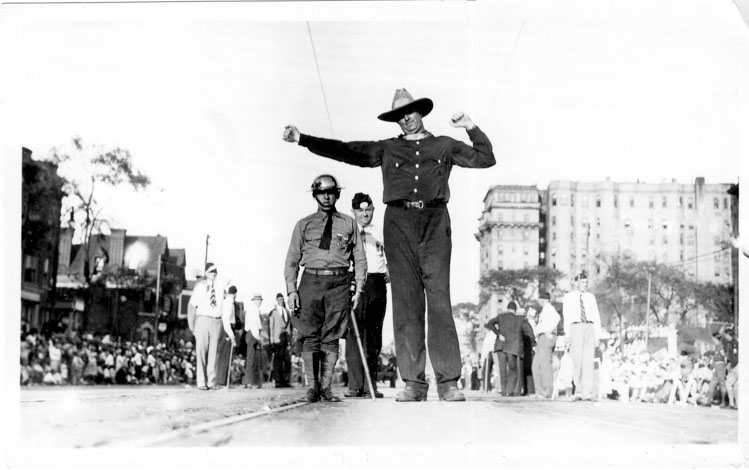

| Buffalo County farmer August Klindt was photographed on a Colorado main street while performing with the circus. |

“How tall are you?” was a question August Klindt probably was asked a hundred times a year. “Six feet, 14 inches,” he sometimes answered, or “five feet, 26 inches.” He probably had a dozen such quips depending on the day and the inquirer, because he was a practiced politician and performer. He left South Dakota in the 1920s and 1930s to perform in circuses with sword swallowers, tattooed ladies and a three-legged woman. But he tired of the freak shows and came home to farm and run for elected office before eventually retiring to Wessington Springs.

“I remember him walking the streets when I was a little boy,” says Craig Wenzel, Wessington Springs’ retired newspaper editor. “I was a kid and he was 7 feet, 2 inches, and when I looked up at him he seemed as big as the sky itself. He wore a 10-gallon hat, like a Hoss Cartwright hat, and he liked to take it off and place it on our heads. It landed on my shoulders and the hat itself never touched my head.”

That hat now hangs in the Wessington Springs museum, along with other memorabilia from the Gann Valley Giant, including a ring he wore (a 50-cent piece, which measures nearly an inch in diameter, fits inside).

South Dakota has spawned other tall men who’ve achieved celebrity status. Mitchell native Mike Miller (6-foot-8) played NBA basketball for 17 years and is now an assistant coach at the University of Memphis. Mitchell Olson, a Vermillion farmer’s son, grew to 7 feet and parlayed his height into a spot on the 2001 Survivor: The Australian Outback reality TV series. He’s now a singer, songwriter and entertainer based in Sioux Falls.

Nate Brown Bull is lesser-known but even taller. He grew to a height of 7-feet-1 on the Pine Ridge Reservation and was a star basketball player for Little Wound High School, graduating in 2015. Foot injuries have interrupted his efforts to launch a college hoops career but he’s still hopeful.

|

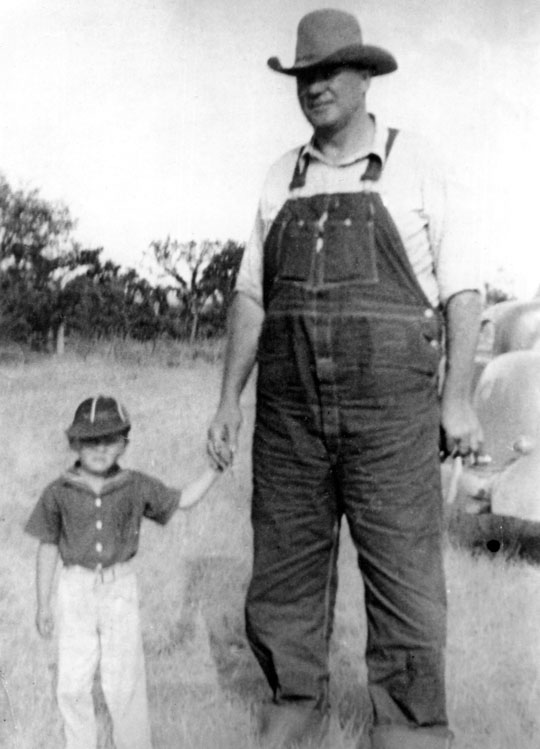

| The Gann Valley Giant always had time for children. In about 1940, he posed with Dennis Younie, who grew up to become a popular auctioneer in Buffalo and Jerauld counties. |

Who knows what the future might hold for these modern-day giants of South Dakota life? It’s unlikely that they’ll join a circus or run for sheriff but — like all of us, short and tall and in between — may they be remembered with the same fondness that the people of Jerauld and Buffalo counties still share for their Gann Valley Giant.

A baby named August was born March 23, 1894 to Henry and Anna Klindt. His parents were of average height, as were his sisters, Lydia and Hazel. A brother, Henry Jr. (later called Prince) was tall but he never reached August’s legendary height or weight.

Mr. Klindt was born in Germany in 1850 and studied to be a doctor, but his education didn’t qualify him for the medical profession in the United States so he immigrated to Dakota Territory. He settled by Elm Creek in Buffalo County, about 3 miles west of the tiny community of Gann Valley.

Little is known about the young giant’s childhood. As he grew (and grew and grew) to adulthood, he stayed on the farm until he eventually succumbed to invitations to join the circus as one of the “freaks” in the traveling shows popularized by P.T. Barnum in the 19th century.

Klindt traveled and performed with a three-legged woman, a two-headed man, a tattooed woman, a sword swallower and others with unusual appearances or talents. To earn extra cash, he hawked 25-cent rings that fit his big fingers. Klindt told the Sioux City Journal in March of 1930 that he liked the work, except for trips to the South where he said malaria “gave him the shakes.”

However, that quasi-positive response may just have been the story of a polished performer. Klindt’s niece, Rosemary Hof, remembers hearing that her Uncle August wasn’t fond of being on display, though there’s little doubt that he got along famously with fellow performers and curious spectators. “He was a very friendly man who always had a big smile,” says Hof, who now lives in Walla Walla, Washington.

Klindt worked for the Sells Floto and the John Robinson circuses in the 1920s and 1930s, good work at a time when Buffalo County and all of South Dakota were mired in drought and depression. He parlayed his show business contacts into a short stint as doorman at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, a Hollywood movie palace still operating today.

Klindt eventually quit show business because of his personal distaste for the exploitation of people with unusual features or physiques, as well as the mistreatment of elephants and other beasts. Later generations came to share this opinion, which led to the demise of such circuses.

Klindt never left Buffalo County for long. He soon utilized his people skills to launch a hometown political career. In 1928, a year after his father was killed in a farm accident, he ran for county judge. The Evening Huronite plugged his candidacy in an article that began, “If size adds prestige to a judge on the bench, August Klindt, Gann Valley, reputed to be the largest South Dakotan, should speak with authority …”

The newspaper described Klindt as, “a single man, 35 years old, 7 feet tall, weighs 350 pounds, wears size 16 shoes [and has] a 22-inch collar. He has toured the country with well-known circus troupes and has played roles in Hollywood film studios.” It’s unlikely that the newspaper editor revealed the heights and weights of the other candidates.

Klindt lost that race, but 10 years later he ran for sheriff, seeking to succeed Morris Nelson, who stood just 5 feet tall and weighed only 125 pounds. As often happens in politics, voters went from one extreme to the other and elected Klindt, who stood at least 26 inches taller and weighed nearly three times as much as Nelson.

August's destiny as a tall man became obvious at an early age. Family photos show him quickly outgrowing his brother, Henry Jr.

“Law breakers will want to watch out for a man measuring 7 feet, 2 1/2 inches, and that weighs 325 pounds when they are trying to escape the law in Buffalo County,” read another article in the Nov. 24, 1935 Evening Huronite. But the giant’s law enforcement career was uneventful. He was a model of Sheriff Andy Griffith, 20 years before there was a Mayberry. Nobody can recall any stories of confrontation during his tenure.

Klindt was re-elected to a second term in 1942 and served until 1945, when he hung up his badge at the age of 51 and returned to full-time farming.

Jim Keyser remembers the Klindt farm as a simple place in a simpler time. “He farmed a little, not really too much,” says Keyser, who now lives in Wessington Springs. “To begin with he had a team of horses and a wagon and an F-20 Farmall tractor. He raised a couple of pigs and some chickens. He never had electricity in his house. He had a wood-burning stove and a kerosene lantern.”

While that may seem like extreme rural poverty today, Keyser said it wasn’t unusual in the 1950s. “When I was little, maybe 6 or 7 years old, I used to walk over to his house to see what he was doing. We’d sit and talk. Sometimes he would let me help him put straw around his rhubarb plants or clean out the chicken house.”

He recalls the giant as a patient man. “Not too many kids know how to put straw around rhubarb, but he taught me,” he says. “I probably walked over there three or four times a week. If he wanted to take a nap, he’d tell me, ‘It’s time for you to go, now.’”

Keyser says Klindt kept a tidy house and yard, and he was not a hermit. “I think he liked the solitude of the farm but he also liked people. He used to ride into town with us on Saturday nights. I remember one time he asked if I had my allowance, and then he reached in his pocket and took out some pennies and filled my two hands. I’ll never forget the size of his big hand covering both of mine.”

Other neighbors also remember giving the giant rides to Wessington Springs. “He had me figured out,” laughs Fred Knight. “We lived 3 miles north of his farm and he could see my car’s cloud of dust from far away so he would be standing by the mailbox looking for a ride. I had a ’55 Plymouth and the car would tip toward the ditch when he got in. His knees were up higher than the dash. I don’t remember him ever owning a vehicle, he just hitched rides.”

Knight says the giant dwarfed his little red Farmall tractor. “I went by his place one day and all I could see was this man going up and down the field. You couldn’t see the tractor because the corn was too high but you could see August gliding over the corn.”

“People liked him,” Knight says. “He was just a big cowboy who wore a big Stetson hat and these big bib overalls. When he got to town, he talked to everybody walking down the street.”

|

| August Klindt posed for pictures on a rock levee near the family farm. His father died from injuries suffered while building the dam in 1927. |

Brookings journalist Chuck Cecil, who was raised in Wessington Springs, says he and other youth always hoped for a sighting of the giant on Saturday nights. He says Klindt cut a “wide swath through the crowd.”

“He wore the biggest bib overalls you ever saw. The legs had been elongated with material that didn’t match and the suspenders had been over-suspended and were over-taxed. We all got awfully quiet when he walked by. We hoped he wouldn’t see us and maybe step on our car.” The giant drove his tractor short distances from the farm, perhaps to Gann Valley or to the Ray Etbauer ranch where he filled water bottles because his own well water was not fit to drink.

Kenneth Wulff, the Buffalo County highway superintendent and proprietor of a little gas station and store in Gann Valley, says everybody liked August Klindt. “When I knew him he never had a car. He drove an old Farmall Regular tractor. Maybe getting in and out of a car was too hard for him. He would drive over to have a visit with us and get some eggs and milk, maybe, and have a meal. He survived with what he had. Nobody had much in those days.”

Klindt made some spending money by occasionally helping neighbors on their farms. One family remembers that he slept on a bed with a chair at the foot to hold his feet. He gathered with the family every evening to sing songs and tell stories.

Storekeepers at Habicht & Habicht in Huron helped dress the giant. They ordered the largest overalls they could find, but even then Klindt needed several inches of material sewn to the bottom of the pant legs, resulting in a cuffed look.

Eventually, the giant left his farm for the comforts of Wessington Springs, where he rented a room in the Hotel Pheasant and often ate his meals at Aggie’s Cafe.

“It was a big hotel, a wooden structure on Main Street, and sort of a retirement place for old guys,” says Wenzel, the newspaperman. “They had a room at the hotel and would sit on their rockers on the front porch at night and watch the street.”

Rosemary Hof, the giant’s niece, also remembers her uncle’s stay at the Pheasant. “He was my mother’s brother, and they stayed close. As a small child, he would always reach out to shake our hand and as a little kid his hand was five times the size of mine. It was kind of a scary feeling, having your hand enclosed in his but he was also very gentle.”

Hof’s family still owns property in Buffalo County. “I try to go back once a year to visit Wessington Springs, my hometown. In our travels, sometimes we run into other South Dakotans who don’t know much about my home area unless you mention the Gann Valley Giant. They’ve heard of him.”

The Gann Valley Giant had several titles. The Sioux City Journal billed him as the Biggest Farmer in South Dakota and the Tallest Mason in a 1927 story. In the circus he was simply called The Large Man.

A contemporary of Klindt, Johan “John” Aasen of Sheyenne, North Dakota, was billed as the tallest man in the world. One report listed him as 8-feet-9, although his actual height was never officially determined. Aasen profited from his physique much more than Klindt; he played a role in the Todd Browning cult classic Freaks in 1932, and also performed in Charlie Chan at the Circus. However, he lost his wealth with the stock market collapse of 1929 and then suffered numerous health issues before succumbing to an infection in 1938. To pay medical bills, Aasen had willed his body to Dr. Charles Humberd of Barnard, Missouri, who later hung the skeleton from his living room ceiling.

Klindt and Aasen lived in an era when Americans were the tallest people in the world. However, as childhood health care and nutrition improved around the globe, people from other countries did more than catch us: today Americans rank 40th in height. People in the Netherlands, Latvia, Estonia and Denmark are tallest.

Today, the average American male stands 5 feet 9 1/2 inches tall, shorter than a century ago. Experts blame our height stagnation on fast food, lack of health care for poor families and overall wealth inequality.

Klindt was never wealthy, not even by Buffalo County standards. Still, he reached the age of 73 before dying in June of 1967 while visiting his brother, Prince, in Aurora, Oregon. His remains were returned to South Dakota and buried alongside his parents at Spring Hill Cemetery near Gann Valley.

There’ll come a day in the not-so-distant future when he’ll be forgotten — like most of us — but 51 years after his death he remains a gentle giant and a country celebrity to everyone who ever stared at him on the streets of Wessington Springs.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2018 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments