The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

A Historical Treasure Hunt

|

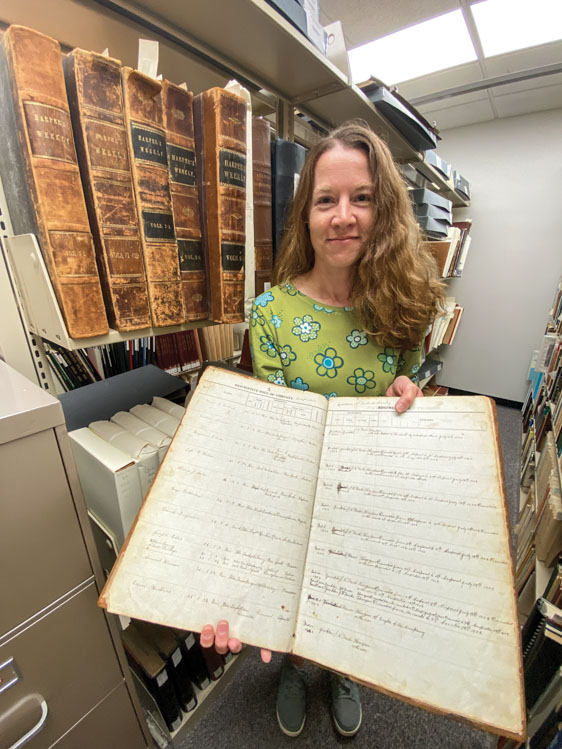

| Sarah Hanson-Pareek, the Curator of Digital Projects and Photographs for the Archives and Special Collections at USD, is digitizing the long-lost 1st Dakota Cavalry ledger, which dates to 1862. |

WHEN ABNER M. ENGLISH wrote a history of the 1st Dakota Cavalry — the first military regiment ever assembled in Dakota Territory — his time in that unit was nearly 35 years behind him. Still, he remembered with remarkable clarity several stories from the cavalry’s three years of active duty — from their training days in Yankton, to the mundane everyday occurrences of a soldier’s life to their pursuit of Native Americans as part of General Alfred Sully’s campaign in northern Dakota.

He tried to recall the names of all his comrades in Company A, a task that would have been much easier had he been able to find the company’s descriptive book, which contained a full roster of the soldiers who joined along with some scant biographical data. However, English believed the book had been lost, and for decades historians of Dakota Territory and South Dakota — as well as descendants of our first military men and other ardent genealogists — also assumed that was the case. But what was lost is now found and will soon be available to anyone in the world with a computer and access to the internet.

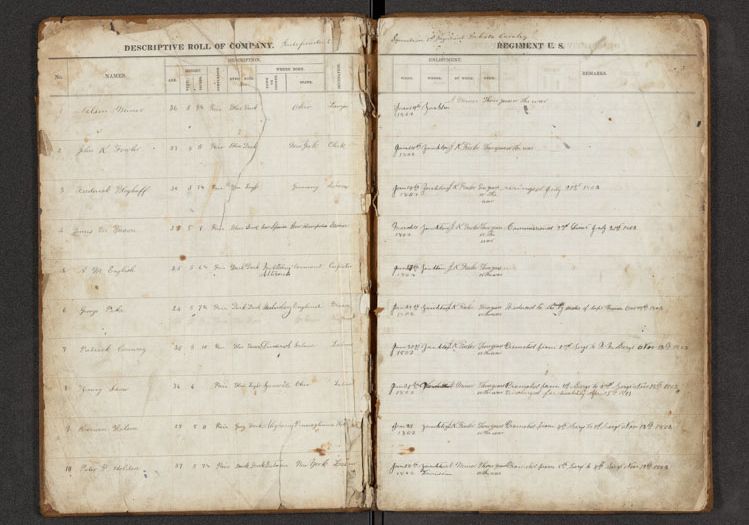

The book is fragile — not surprising considering it is 160 years old. It contains a dozen pages of written names, ages, heights and hometowns or countries. At first glance, it appears to be nothing more than a list, but it has the potential to unlock countless stories that can tell us much more about the early days of Dakota Territory.

*****

AMONG JAMES BUCHANAN’S final acts as president of the United States was signing the document officially creating Dakota Territory on March 2, 1861, two days before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln. That fall, the War Department authorized Gov. William Jayne (Lincoln’s personal physician from Springfield, Illinois and political appointee) to raise two companies of cavalry. As new states and territories were created, they were authorized under the Militia Act of 1792 to raise military units.

Kurt Hackemer, a history professor at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion who researches the Civil War era in Dakota, says those units were raised for varying purposes, largely depending upon geography. “In the South you have militias before the Civil War because of the threat of slave rebellion,” Hackemer says. “As you get into the Industrial Age, in parts of the Northeast and Midwest, militias exist in response to industrial violence. In Dakota Territory, when our militia is founded, it’s for protection because there’s contested land between the incoming settlers and the indigenous population.”

Recruiting stations were set up at Yankton, Vermillion and Bon Homme. As volunteers reported to each community, their vital information was recorded in a descriptive book: name, age, height, complexion, eye and hair color, home state or country, occupation and enlistment date. Company A of the 1st Dakota Cavalry officially mustered into service on April 30, 1862. (Company B, also known as the Dakota Rangers, mustered in at Sioux City on March 31, 1863.)

English, a 25-year-old carpenter from Vermont when he joined, later recalled the first weeks of the Dakota Cavalry’s existence. His reminiscence was serialized in 1900 and 1901 in the Monthly South Dakotan, state historian Doane Robinson’s turn-of-the-century version of a magazine devoted to history and culture. It was republished in its entirety in 1918 in the historical society’s South Dakota Historical Collections. English said the men trained under a regular army soldier named Frederick Plughoff, a 36-year-old from Germany. “His strict discipline was quite irksome but we had enlisted to become soldiers and to serve under the flag of our country and we obeyed all orders and soon became quite proficient in drill and discipline,” English wrote.

He said soldiers were issued old Hall’s carbines, French revolvers and a regulation cavalry saber. “The carbine and revolvers were miserable arms,” English wrote, “the men being in about as much danger in the rear as the enemy in front.” They were soon replaced with Sharp’s carbines and Colt revolvers.

|

| Nelson Miner served as captain of the 1st Dakota. Company A's original roster book remained in his family until the 1980s. |

Although the Civil War was raging in the East and cavalry units from surrounding states were called to help fortify Union forces, much of the 1st Dakota Cavalry’s early actions took place close to home. “There’s an interesting misnomer that the Civil War was fought on the Union side by the U.S. Army, and it really wasn’t,” Hackemer says. “There are Army units, but the vast majority of forces raised during the Civil War are state-level units called volunteers in federal service. They are units that are under the authority of state governments who then sign up to serve in federal service, and that’s what the Dakota Cavalry is. They could have been sent east, in theory, to serve in Civil War battles like the 1st Nebraska Cavalry was, but they were kept here for local service because of the threat posed by the 1862 Dakota War.”

That conflict between the U.S. Army and the Santee erupted in violence in Minnesota in August of 1862 and spilled over into Dakota and Nebraska. English recalled that a detachment of 15 soldiers chased several Native Americans on horseback near Sioux Falls in the weeks before Judge Joseph B. Amidon and his son Willie were killed while cutting hay on a homestead claim on August 25. Soldiers and Indians actually fired upon each other in a skirmish near the James River east of Yankton. When rumors began circulating that the Yankton Sioux Tribe planned to join the Santee in war in southeastern Dakota, many residents of the new communities of Yankton, Vermillion and Bon Homme fled to Sioux City. Dakota Cavalry soldiers then helped build the Yankton Stockade, a 450-foot square fortification surrounding roughly a quarter of each block at the corner of Broadway and Third Street (historical markers still note the placement of the four sod and lumber walls).

Soldiers from Company A were also dispatched to Nebraska in July of 1863 following the murders of the five children of Henson and Phoebe Wiseman, who lived on a homestead in the Missouri River foothills south of Meckling. Henson was travelling through Dakota with Company I of the 2nd Nebraska Cavalry, which was under the command of Gen. Alfred Sully and ordered to push the Santee fleeing from Minnesota further west. Phoebe had traveled to Yankton to purchase supplies. She returned home and found her children — ages 16, 14, 9, 8 and 4 — dead or dying. The Yankton and Santee were blamed for the killings, though it was never proven.

In 1864, the 1st Dakota accompanied Gen. Alfred Sully on a campaign up the Missouri River into northern Dakota Territory. They saw action at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain in July, in which Sully’s force of 2,200 soldiers defeated roughly 1,600 Lakota, Yanktonai and Santee under the leadership of Gall, Sitting Bull and Inkpaduta. In August of 1865, a detachment of 24 soldiers from Company B took part in the Battle of Bone Pile Creek near present-day Wright, Wyoming. Privates Anthony Nelson and John Rouse were killed, the only combat deaths the 1st Dakota ever experienced.

Two other soldiers, James Cummings and John McBee, died from illness at the Fort Randall hospital. John Tallman died during the winter of 1864-65 when he crossed the Missouri River south of Vermillion to hunt deer and never returned. A settler found his frozen body lying on the ground and wrapped in a blanket. He was given a military funeral and buried in an unmarked grave on a bluff near Vermillion.

The rest of the 1st Dakota spent that winter in Vermillion, as well. When spring arrived, English wrote, “We rejoiced over the surrender of Lee and were depressed by the news of Lincoln’s death, but our spirits were soon revived by information that we would be mustered out on May 9.” Capt. Hugh Theaker of the regular army arrived to conduct the ceremony. “Then came the last roll call, the usual farewells, and the members of A company were out of the United States service, never as an organization to meet again.”

*****

YANKTON HISTORIAN Bob Hanson was always proud of his family’s long history in Dakota. His great-grandfather, Amund Hanson, immigrated from Eide, Norway, and was among the first settlers in Clay County in the early 1860s. He donated a portion of his land to build the Hanson School, among the first schools in the new Dakota Territory, and in 1862 he joined Company A of the 1st Dakota Cavalry as its bugler. That family connection to Dakota’s first volunteer soldiers fueled Bob’s passion for finding the long-lost ledger.

|

| 1st Dakota soldiers helped build the first school in Dakota Territory in Vermillion. The road in the photo is today's Dakota Street. A monument along the road below the bluff marks the spot. |

An introductory note to the 1918 republishing of English’s memoir reports that the descriptive book and roster for Company B was donated to the state historical society by the widow of Uriah Wood, a former soldier who had kept the book as “his most precious relic,” but on his deathbed in 1916 insisted it be turned over to the state. The note also laments the loss of Company A’s descriptive book. Historians apparently contacted the War Department in Washington, D.C., but the adjutant general replied that there was no record of it.

Fortunately, a historical treasure hunt was exactly what Bob Hanson loved. He worked diligently in the 1990s to locate the unmarked grave of John Tallman and place a stone there. Though he believed he knew where the soldier was buried, a stone never came to fruition before his death in 2018. He was successful in Yankton, however, where the final resting place of Pierre Dorion, an early explorer and interpreter for Lewis and Clark, is memorialized with a large boulder at West Second Street and Riverside Drive.

We’ll never know how many letters Bob wrote, phone calls he placed or visits he made to others who were connected to the early days of Dakota. But his daughter, Sarah Hanson-Pareek, recalls a conversation with him shortly after she went to work in the archives of the I.D. Weeks Library at the University of South Dakota. “He asked if we still had Grace Beede’s hat box,” Sarah remembers. “He said the missing ledger was in there and not to let anyone know we had it. I think he was afraid that some government archive might ask for it. He thought it belonged here because it was so important to our history.”

Discovering the book in the Beede collection allowed historians to construct its possible life story. It begins with Nelson Miner, the 36-year-old lawyer from Ohio who became Company A’s first captain. Miner was born in 1827 and came to Dakota Territory with his wife, Cordelia, in 1860. When the War Department authorized raising the 1st Dakota, Miner became the recruiting officer at the Vermillion station. After ably leading the cavalry for three years, he was appointed registrar of the U.S. Land Office in Vermillion. Miner also owned the St. Nicholas Hotel and was elected to the territorial legislature in 1872, 1876 and 1878, but died in October of 1879 before his final term expired.

Just as Uriah Wood kept the roster for Company B, it seems Miner held on to its counterpart from Company A as his own “precious relic.” It passed through the family until it ended up with Grace Beede, his great-granddaughter. Beede, born in 1905, earned a bachelor’s degree at USD in 1926 and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1936. She joined the faculty at USD in 1928 and taught classics there until 1970. She donated the Beede Family Papers to the USD Archives in 1985, five years before she died. Today’s Coyotes might better recognize her as the namesake of Beede Hall, a girls’ dormitory within the campus’ North Complex along Cherry Street.

*****

KEEPING THE LEDGER’S location a secret was never a top priority for campus librarians, but Bob Hanson’s rediscovery of it in the late 1980s certainly didn’t make a lot of headlines, either. Still, knowing the artifact is right across campus opens a lot of doors for historians like Kurt Hackemer.

“Having it here is pretty exciting,” he says. “At first glance, things like rosters look pretty boring. But the real value of a roster like this is when you see who is serving in a military unit you can then find those names in other records, and you can start building a story about the 1st Dakota Cavalry that is far more than just what the unit did.”

Among those records Hackemer hopes to utilize is a special 1885 census. Congress offered to pay half the costs of conducting an off-cycle census, but only a few states and territories accepted, including Dakota Territory. While debating its structure, territorial legislators created a special schedule within the census to catalog veterans. “They specifically wanted those settlers to be remembered for posterity’s sake. That was their goal,” Hackemer says. “It is the only census of its kind that you can find at a state or territorial level anywhere in the United States. When I’ve taken my research about this to national conferences, historians are floored. There is literally nothing like it anywhere else in the United States.”

|

| The ledger contains a dozen handwritten pages that record the names, ages, heights and hometowns or countries of the 1st Dakota soldiers. |

Comparing the 1st Dakota roster to that census and subsequent counts could lead to countless research projects, articles and books. “I learn a lot more about the men who made up that unit and it lets me ask interesting questions,” Hackemer says. “Who felt compelled to volunteer for military service and why? Who thinks they have a stake in this? There are both native born American citizens and immigrants living in Dakota Territory at the time. Is one group more or less likely to volunteer and why? It can help tell you a lot about the creation and the early years of the territory, and for a historian, that’s exciting. There are a lot more stories to be told there.”

When Bob Hanson located the ledger, he had it photographed for preservation. This past summer, his daughter Sarah — the Curator of Digital Projects and Photographs for the Archives and Special Collections at USD — photographed it again to the highest standards of digital preservation in the country. The archives was awarded a CARES Act grant of $193,000 to purchase new equipment to help make primary source and collection materials available to a larger global audience. “Because of COVID and the inability for researchers to travel as easily, there really is this increased need to get materials online for distance researchers,” Hanson-Pareek says.

The new equipment allows archivists at USD to digitize documents, archival manuscript materials, bound volumes, maps, oversize materials, film and glass plate negatives and two-dimensional artworks at standards that comply with FADGI, the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative, a collaborative effort launched in 2007 to establish common practices and guidelines for digitization. “We’ve never had the equipment to do it justice,” Hanson-Pareek says of the ledger. “But with this grant funding, we have a camera with significant resolution and power to digitize it.”

The cavalry ledger is among the first historic documents to be digitized with the new equipment, along with a scrapbook belonging to John Blair Smith Todd and a ledger from Cuthbert DuCharme’s trading post. All will be available to researchers online this fall, but for historians curious to see the real thing, the USD Archives — after a long closure due to the pandemic and an extensive renovation project — plans a full reopening in October. Sarah Hanson-Pareek will be there, and her father will be in spirit.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2022 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments