The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Night Walking South Dakota

|

| John Banasiak in his office at the University of South Dakota, where he has taught since 1980. |

John Banasiak is a passionate experimenter. As we sit in his office at the University of South Dakota — filled with prints, cameras and other ephemera collected over nearly 50 years of teaching — he talks about something that’s been on his mind at least that long. “Over the summer I tried to tweak this process that I did years ago, and I stopped because I almost burned my house down doing it,” he says. “But I thought there had to be some way to do it.”

Back when he attended the School at The Art Institute of Chicago, a professor told him, “You know photography exists, but there are lots of ways to get to it. You invent photography.” That led to an interesting mash up of photography and biology in which he purloined several of his mother’s begonias and put them in the closet, hoping the darkness would manipulate the starches. Later, he taped negatives to the leaves and replaced them in sunlight. He expected the combination of light and starch would produce an image. It kind of worked, but more than 50 years later he thought he’d revisit it by boiling leaves in ethyl alcohol to remove the green caused by the plant’s chlorophyll. “But at a certain temperature it catches fire,” he says with a laugh. “So that was the problem. I threw the pan out the window and there were all these flames. It was crazy.”

Digital photography has captured the 21st century — even in Banasiak’s classes — but there’s still a bit of mad scientist in him that enjoys tinkering with solutions and creating photographs that bring him and his students to places they’ve never been. “There are so many things you can do in a darkroom. There are all these magic tricks you can do that help invent some language, and it’s shocking to people. Then they go on and do it for years. They’re looking for some language, and when they see it happen, they want to do it.”

Thousands of students have found inspiration in Banasiak’s methods, but a career in art was never something the people in his neighborhood on the south side of Chicago envisioned for him. His grandparents from Poland and Ukraine settled there during World War I, finding comfort in the steady work provided by the factories that had popped up along the southern shores of Lake Michigan. Banasiak, born in 1950, was destined to follow his father and uncles into a lifetime of factory work until a teacher at his Catholic grade school noted his artistic ability. In high school, his art teacher pushed him to apply to the Art Institute of Chicago, eventually landing him a full scholarship to attend classes there in the fall of 1968.

|

| A television set peeks out of a repair shop window in Kadoka. |

He was admitted based on his talents in drawing and painting, but then he took a class in photography. “The only time I would have ever taken any photos would be for family gatherings, birthdays, graduations,” he says. “Sometimes my mother would hand me the Kodak twin lens reflex and I’d take a shot. I was just nervous I would shake or jiggle the camera because film was expensive, so I didn’t really relate to it at all.”

He loved the poetry of photography, especially in late-night photos that he captured while much of Chicago slept. Banasiak worked as a night watchman at the Art Institute. When his shift was over at 2 a.m., sometimes he stayed. “I slept under Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. I’d wake up to that,” he says. “There was Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge down that way and The Old Guitarist by Picasso. There was a Rousseau jungle painting and van Gogh’s bedroom in Arles. It was my favorite gallery, and I’d just sleep there on one of the cots because I had to get up early for my art history class that was right downstairs.

“On occasion, I didn’t feel like going to sleep and I’d just walk around Chicago with my camera. I like walking around at night. It was like a stage set waiting for the actors to show up. During the day, the sun would move, there would be light and shadows and it would all change. At night, there would be streetlights and it would stay like that for six hours. I could move around and get what I wanted.”

The results included poignant images of alleys, storefronts and other urban settings seen in a different way. It was the beginning of his “Night Walks” series, a constantly growing collection of photographs that continued after he moved to Vermillion in 1980. Though he was 500 miles from urban Chicago, Banasiak found commonalities as he explored his new, more rural home at night. “The atmosphere of the environment is all you need to make up stories. I think they’re part of my wanderings in my memory bank. When I see something, I’m drawn to it because it’s a familiar place. It resembles something of an environment that I have in my mind. They’re kind of archetypal, in my own head. Maybe other people don’t see anything in them. But I see something because they just look so familiar, even though they’re taken in different places.”

|

| A UFO merry-go-round at a playground near Lewis and Clark Lake. |

After graduating from the School of the Art Institute, Banasiak received a grant to attend the University of Krakow in Poland. He returned to earn an M.F.A. at the Art Institute in 1975. He served as artist in residence at Light Work and Syracuse University and spent a year teaching at the State University of New York in Oswego. He’d always wanted to explore the South Pacific, so he moved to New Zealand in 1979 and spent a year conducting photo workshops and teaching.

He seriously considered staying, but his mother called to tell him he’d won a sizable grant from the Illinois Arts Council. When he got home, he discovered they’d awarded the grant to someone else because he had been so difficult to reach in New Zealand. He was organizing notes and photos from his travels when someone from the Art Institute told him the University of South Dakota needed a full-time photography teacher.

“It looks just like New Zealand out there,” they told him. “And it did kind of look like central New Zealand. There was the river. I looked it up. And they showed a picture in this encyclopedia of East Hall, and I thought it looked like the Harvard of the West.”

His brother drove him to South Dakota for an interview. When John Day, the longtime chair of the art department and dean of the College of Fine Arts, called to tell him he had the job, he figured he’d stay for a year or two. “But I met all these great people, and the faculty, we’d meet for dinner almost every other night. I loved it out here, and it was peaceful. I applied to a couple of other schools, but I just couldn’t see myself leaving Vermillion.”

One or two years has turned into 44. Sabbaticals took him to Morocco, Jordan, Ecuador, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba and China. Back home, his teaching brought numerous faculty awards as well as the 2021 Governor’s Award in the Arts for Outstanding Service in Arts Education.

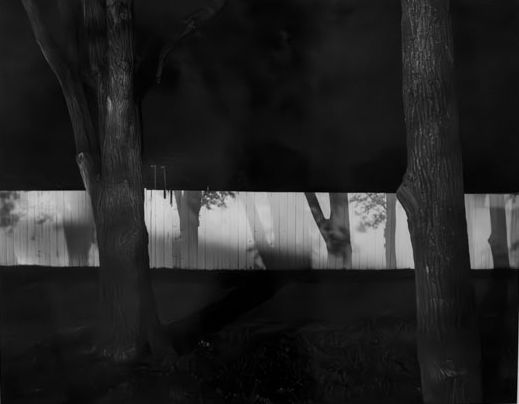

|

| A collection of tree shadows on the outfield fence at Riverside Park in Yankton. |

Those honors are wonderful, but it’s clear that Banasiak’s passion will always be the photographic process. “I bought some beet powder not long ago,” he says, and sure enough, a package of beet powder rests on a counter beside some turmeric and other chemicals. He’s exploring how emulsions made from different plant juices produce images.

“The past couple years I’ve been kind of exploring, tweaking and rearranging possible processes,” he says. “When I do something, I like doing the whole process. When I get done, I’m done with it. I don’t care if I exhibit or sell them. It’s really in the meditative process of doing it. Whatever I learn doing my own art is what I end up teaching. Classes are always different. I’m coming up with new ideas. I’m excited by them, and when I share them with the students they go nuts.”

The idea of retirement is a non-starter. He’ll invent and teach as long as he’s able. He knows infirmities come to all who live long enough, but he’s thought about that. “Sometimes, now that my eyes are having some issues, I might experiment with photographic braille,” he says. “I don’t think that’s out of the realm of possibility. I might try printing some photos on wood or plastic with the laser cutter that we have in the graphics department. To see with the touch of fingertips can be something worth exploring photographically. I don’t really believe people see with their eyes anyway, they see through their eyes, and it makes me think, ‘What else might I be able to see with?’”

If there’s a way, John Banasiak the experimenter will find it.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments