The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Baum's Aberdeen Oz Was a Baseball Diamond

Editor’s Note: Some of the material in this story came from the Spring 2000 South Dakota History article “Wizard Behind the Plate: L. Frank Baum, the Hub City Nine, and Baseball on the Prairie” by Michael Patrick Hearn. This story is revised from its original appearance in the May/June 2001 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Beside the immigrant drawn by free homestead land, the other “typical” settler on the Dakota frontier of 1888 was young, restless and looking to escape the maddening crowd back east. Lyman Frank Baum was the second type.

Baum found room to breathe in Aberdeen. He opened Baum’s Bazaar, and stocked it with the non-essentials of life: fancy goods, sporting equipment, toys and amateur photography supplies, among other novelties. With creative advertisements that hinted at his hitherto hidden literary talent, he pulled his customers in:

At Baum’s Bazaar you’ll find by far

The finest goods in town

The cheapest, too, as you’ll find true

If you’ll just step around

Baum believed Aberdeen would embrace such a business, for it was no one-horse prairie pothole. The Hub City was progressive — there were 20 hotels, a library, four restaurants and a half-dozen newspapers in town. Electric light service and telephones were available. With the addition of Baum’s store, Aberdeen had everything a civilized town might want or need.

Except a baseball team. An ardent “crank,” as baseball fans were then known, Baum felt the lack keenly. Less than a year after he arrived in Aberdeen, L. Frank Baum helped bring a group of local businessmen together to field a team. They were so impressed with his enthusiasm and ideas they made him secretary, responsible for the club’s day-to-day affairs. A subscription of 300 shares sold out quickly, and the Hub City Nine were on their way.

Baum’s Bazaar supplied uniforms and other equipment for the team. Players earned $50 a month plus room and board, and as a further incentive, one of the owners offered a box of cigars to the first man who hit the ball over the center field fence. After playing the likes of Groton, Redfield and Claremont, Baum managed to lure the St. Paul Indians to town for what promised to be the game of the season. The Milwaukee railroad ran three extra trains to bring fans to town. Admission was raised from 25 to 50 cents, but after some grumbling, the fans came anyway.

There was heavy rain the night before, but game day dawned bright and sunny. After playing the powerful Indians tight in the morning, losing only 2-1, the locals were thumped 17-3 in the afternoon. It hardly mattered. “(The contests) gave the public an opportunity to see what good ball playing is,” observed the Aberdeen Daily News philosophically, and just as importantly, the big gate had replenished the team’s treasury. Baseball’s future in Aberdeen seemed assured.

|

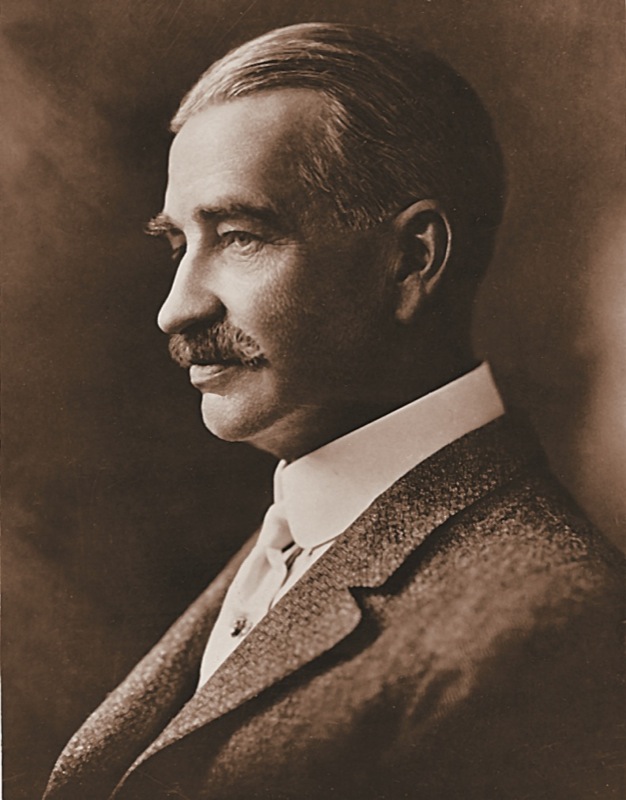

| Hub City baseball booster L. Frank Baum. |

There was only one fly in the ointment that glorious summer. At some of the games, “there was fully one-half as many people perched on the fence and on buildings and elevations surrounding as there were within the enclosure,” grumbled the Daily News. That was robbing the team of needed revenue, and while the paper implored fans to cease this “most detestable practice” in general, it took particular aim at Lester J. Ives, who owned a house near the new baseball park. It seems the enterprising Mr. Ives was selling seats on his roof for ten cents, so people could watch the games.

“The antics of this individual…have thoroughly disgusted the people without exception,” fumed the editor. “He is evidently a baseball crank — but of the hog species — without shame or self-respect.”

To counter Ives and his cheap seat “hoodlums” the ball club erected a high latticework on top of the existing fence, to obscure their view. Lester responded by putting high chairs on the ridge of the roof, which forced the management to string canvas atop the lattice. At one point the dispute got so intense that team manager Henry Marple ran a hose from the railroad roundhouse and threatened to turn it on the people engaged in their “sneaking game of looking over the fence. (If) the powerful stream [should] knock Ives & Co. from the rooftops and result in their death, over thirty of the stockholders, all business men, have guaranteed the management to stand by them and pay funeral expenses if required.”

Cooler heads, including Baum’s, prevailed before it came to that. “Mr. Ives is not so black as he has been painted,” Baum wrote following a blistering attack in the newspaper, and the whole affair was eventually settled amicably.

At least some of the displaced rooftop fans, presumably, made their way back as regular, paying customers, but not enough of them. Though the Hub City Nine was an unqualified success on the field — they reigned as the unofficial champions of North and South Dakota after defeating the best teams in both states — the club lost $1,000 that year despite the team secretary’s unstinting effort. “If we have a baseball team next year,” a disillusioned Baum said after the season, “I am of the opinion that someone else will have to do the work.”

Sadly, L. Frank Baum’s novelty store fared no better. After barely more than a year in business, it was given over to his creditors. Baum termed this a “temporary embarrassment,” but it was also fortuitous in that it turned him closer toward his true calling. He bought a newspaper, renamed it the Saturday Pioneer, and was on his way. Aberdeen liked his lively writing style, but Baum’s career as a newspaper owner was all too brief: the Pioneer died shortly after its first birthday. Health problems, coupled with the stress and worry of being a business owner, caused him to move on once again. Baum took a newspaper job in Chicago, and Aberdeen’s soon-to-be-famous crank never returned.

Comments