The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

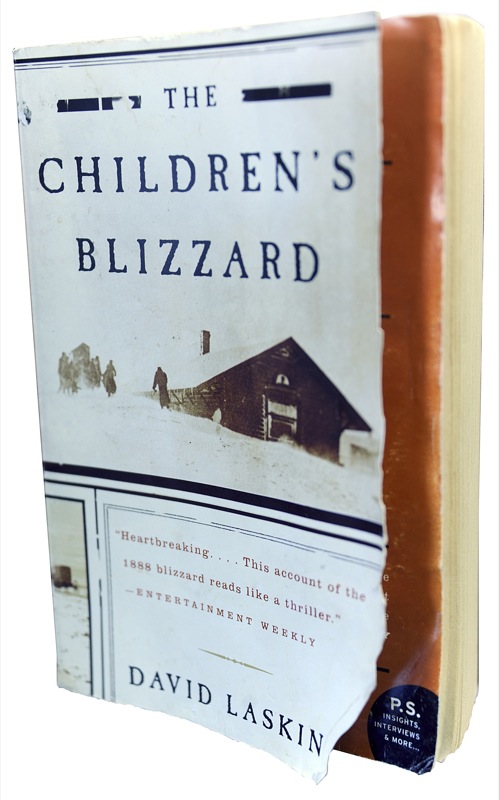

A Somber Winter Read

Dec 27, 2012

|

| The Children's Blizzard by David Laskin revisits the deadly blizzard of January 12, 1888, in which more than 200 people lost their lives. |

There are few more comforting things than a hot cup of coffee and a good book to read while waiting out a South Dakota snow storm. Those are luxuries the characters in David Laskin's The Children's Blizzard didn't have. They were simply trying to make it through the day alive.

I recently noticed a copy of The Children's Blizzard on our shelves, and was ashamed to admit that I had never read it. Most Dakotans have at least heard of The Children's Blizzard, which hit on Jan. 12, 1888, and know that ranks among our worst natural disasters. More than 200 people died, most of them children walking home from school in southeastern Dakota. So I thought that in advance of the 125th anniversary of the devastating storm that I should read the book, and I highly recommend that if you live here, or grew up here, or have any ties to South Dakota whatsoever, that you read it too.

I've often seen book reviewers claim that a work of nonfiction "reads like a novel." Then I read the book and wonder if the reviewer and I read the same thing. But Laskin's book honestly fits that description. You can almost feel the harsh wind and subzero temperatures numbing your fingers as he describes the plight of the children caught in nature's ferocity. You find yourself hoping that the children walking blindly through the snow are discovered alive, but in most cases you're left feeling hollow when rescuers find the frozen bodies strewn across the Plains days later.

The day dawned mild for January in Dakota. Some parents took advantage of the unseasonable weather and kept children home from school to help with farm chores. Those who attended that day walked to school wearing light clothing. Laskin traces the cold front as it raced down from Canada, across Montana, Dakota, and Nebraska. Eventually it affected people as far south as Galveston, Texas. The story was the same in every school house: lessons came to an abrupt halt when teachers and students heard the first gust of wind slam into the northwest wall of their tiny schoolhouses. There are stories of teachers who kept students inside. They kept warm by burning everything they could find. They told stories and held recitations throughout the night. But Laskin's stories are mostly about the teachers and students who chose to brave the elements, thinking they could walk a mile or less to the nearest farmhouse or barn.

They nearly all end in tragedy. One exception is the story of 8-year-old Walter Allen, who attended school in Groton. When the storm struck, fathers drove teams of horses pulling sleighs to the schoolhouse just west of town. Students piled on and they headed into the blizzard. But then Walter remembered his prized possession: a tiny glass perfume bottle of water that he kept in his desk for cleaning his slate. Walter knew it would freeze and crack if left in his desk, so he jumped off and headed into the school to retrieve it. When he emerged the sleighs had disappeared. The boy tried walking back into town but soon became disoriented. Only a heroic rescue mission by his father and older brother saved his life.

Also fascinating is the description of meteorology in 1888. Members of the U.S. Army's Signal Corps were responsible for taking daily observations and filing "indications" reports, which were fairly crude forecasts transmitted via telegraph. They had a pretty good idea of how weather behaved, but a combination of errors and laziness on the parts of certain observers resulted in citizens hearing the first warnings of the pending storm just minutes before it struck.

Good writing makes you feel something, and Laskin's work does just that. Back in September we sought help from Watertown bibliophile Donus Roberts in publishing a list of books every South Dakotan should read. Laskin's The Children's Blizzard didn't make Roberts' final cut, but I'd happily add it to the list.

Comments

unbelievable hardship. We should all be terribly proud of our strong heritage.

While Wilhelm was in town the blizzard of 1888 hit on January 12 and many of the towns folks begged Wilhelm to stay until the storm had passed. He knew he couldn't stay and needed to get home to Kate. Little did he realize she had given birth to their son by herself in their sod home. Meanwhile back home Kate kept her and the baby warm by staying in bed because she had run out of things to burn in their stove. It was bitterly cold.

As Wilhelm headed back home the wind howled fiercely. He stayed with his horses, but they both of suffocation and froze in the storm. The wind and snow were that severe. Wilhelm was able to find some shelter in an old barn that had pigs in it. He crawled in with the pigs to try to keep warm. He was out on the prairie for three days and nights.

Wilhelm was able to make it back home to find Kate and his newborn son cold, but still alive cuddled up in bed. Wilhelm made a fire with the coal he carried back home from town.

This information was passed down from family letters written about the event.

Several years ago, I was reading the South Dakota Magazine issue about famous blizzards. I called my mother and asked her more about the storm that my grandmother and her family talked about over 50 years ago and how that really made an impression with me and the details I remembered even though I was a young girl.

It turns out that my grandfather's brother died in the famous 1888 Children's Blizzard. His name was Fredrick Hoff and he was 10 years old at the time of the blizzard. He attended a country school in Bon Homme County. The teacher at the country school dismissed school and sadly his walk home turned to tragedy. His body was found caught on a barbed wire fence after the storm.

Since reading the article in the South Dakota Magazine, I have read several books about the Children's Blizzard and also found Fredrick's name on the list of those who died in the blizzard. He is listed as the son of Michael Huff, however, it is supposed to be spelled Hoff.

I can’t even imagine wearing light clothing in those elements.