The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Dunlap Melons

|

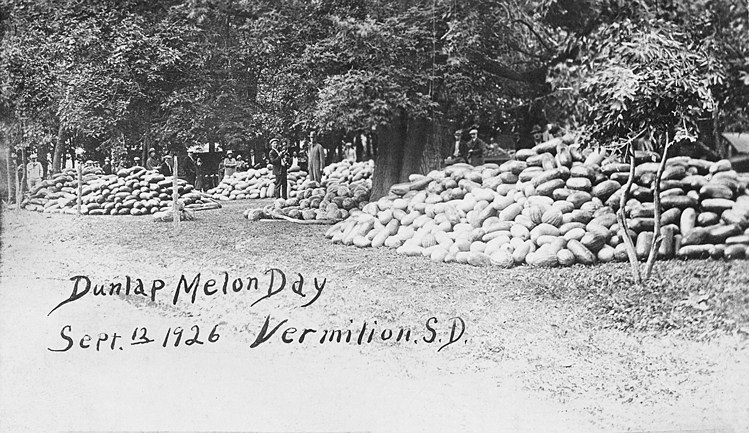

| On Dunlap Melon Day, Sept. 12, 1926 in Vermillion, 22,000 melons were piled and sold by 5 p.m. An estimated crowd of 8,000 to 10,000 people attended. |

We had five seasons in Clay County: spring, summer, watermelon, fall and winter.

My grandfather, Jim Dunlap, began shipping melons from Vermillion as early as 1912. There have been several other colorful watermelon growers in the area. Grandpa earned his crown as the watermelon king in the 1920s when he cultivated 145 acres on the Missouri River bottoms.

For royalty, he worked very hard. In those early years, he walked two miles to his fields. In later years he rose at the crack of dawn, got in a truck, picked up the field hands, and drove down to the fields.

He came back exhausted. After our evening meal he would walk out on the front sidewalk, with his head raised toward the clouds (if there were any) and pray for rain.

In 1930, it was very hot and dry. His daughter, Lenette, told me, "For six weeks it didn't rain a drop and each day Dad would say that he didn't see how the melons could live much longer without rain. He would go down in the morning and the vines were all fresh and perky and looked good. He would go back in the evening and they looked withered and dead."

|

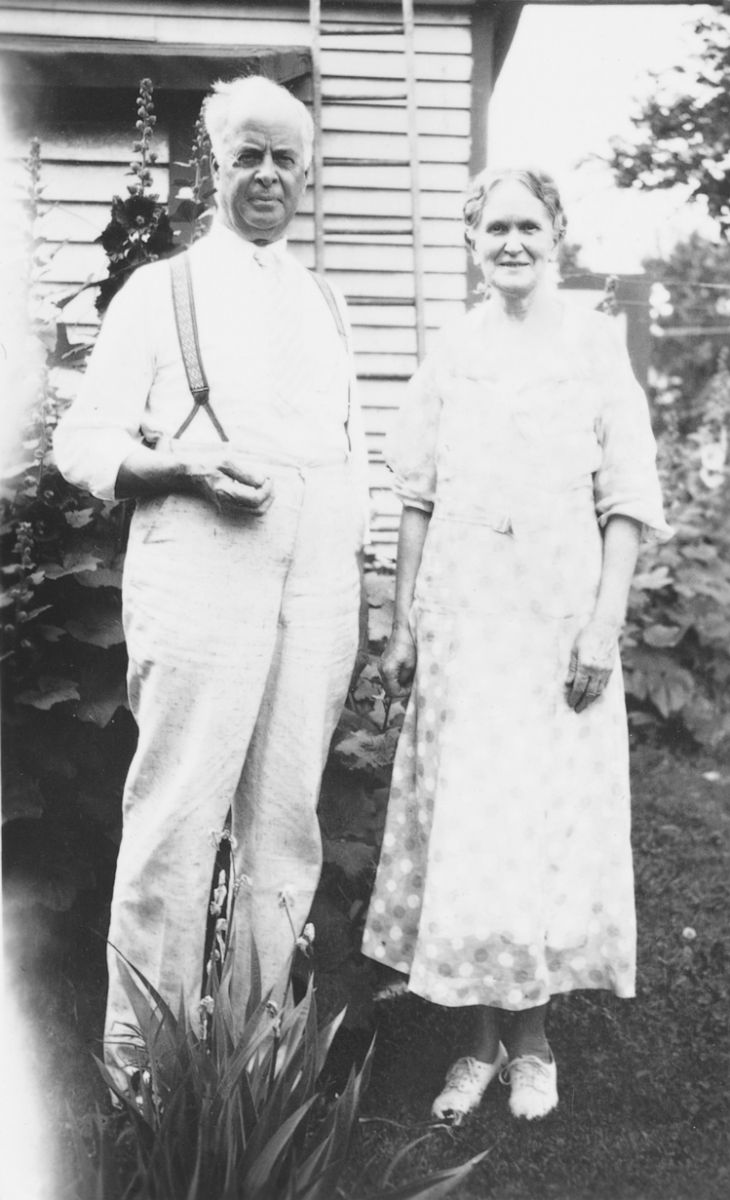

| James and Abbie Dunlap in 1935. |

Finally, rain came on August 18. "Dad had one of his best melon crops," Lenette recalled. "The roots kept going down for water and everyone thought the melons were sweeter that year than they had ever been."

Lenette and her sister, Mary, enjoyed their father's Melon Days promotion and his watermelon feeds. "Of course, the free feed was to entice people to drive down to the grove to buy melons to take home," Mary said. "We had planks for a big, long table, probably 30 feet long, and behind the table were three or four men with machetes and these men would reach back in the pile of melons, put a melon up on the table, and slash it into slices."

Grandpa Dunlap also sold rail car loads of melons to area towns for big feeds. The Milwaukee Railroad once paid him $265 in damages for a shipment that was not packed in ice. When that happened and the weather got hot there would be watermelon juice all over the train.

Rail companies eventually learned to use an open stock car so the melons could get air, but there was still a downside: Opportunists carved out pieces of melon along the way.

On Melon Days in the Great Depression, our family sold surplus melons for $2 a carload. Drivers came with the seats removed from their cars so they could squeeze in more melons.

''They would pile melons into their cars until they were practically falling out and then they would try to drive up the hill to get back on the road," Mary said. "Many of them did not have the power to do this so they would have to stop, unload some melons, put them on the ground, drive their car up to the road, run back and get the melons, stick them back in their car, and then they would go on their way."

Anna Bruce, a Lesterville farm girl, came to board with the Dunlaps so she could attend classes at the university. She didn't know our family grew melons.

On her first day in town, she had a date. She and her friend met some other young people and somebody suggested that they swipe a melon.

A neighbor alerted Grandpa by telephone. "Dad walked down (to the patch), and as he approached the youngsters he struck a match to see the face of the person nearest to him," Mary said. "To his surprise, it was Anna Bruce."

Rather than embarrass Anna, he told all the young people to meet him back at his house. “I don't know what he said to them," Mary said. "But he gave them a watermelon to eat."

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2000 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments