The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Fort Sisseton Kid

|

| Without help from Robert Perry, Fort Sisseton may have been reduced to a pile of rubble overgrown with weeds. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

In 1862, simmering tensions between the Santee Dakota and white settlers boiled into open conflict along the Minnesota River in south-central Minnesota. Known to history as the Sioux Uprising, the war ran its course in a little over five bloody weeks. About 500 settlers were killed during the fighting; at the very least 20 Indians died, along with another 38 who were hanged in the conflict's aftermath.

In the wake of it all, white determination to prevent a reoccurrence of those events led President Abraham Lincoln to authorize construction of a chain of military forts stretching from Minnesota north into Dakota Territory. Soldiers sited one of these in what is now northeastern South Dakota, at the head of the region known as the Coteau des Prairie, and named it Fort Wadsworth.

Completed in 1864, the outpost was later renamed Fort Sisseton, a moniker it carried until the army abandoned it in 1889. Twenty-seven men served as post commander during that span, and nine military units occupied the station.

But the fort's staunchest defender, the Fort Sisseton Kid, was neither a commander nor a member of any of those units. He couldn't have been. He wasn't born until 27 years after the post closed.

Robert J. Perry, who would later be called The Fort Sisseton Kid, first saw the abandoned frontier outpost as a child in the late I 920s. He remembers traveling with his father the 70 or so miles east to the fort from their home in Aberdeen. History was a family passion, and Judge Van Buren Perry took every opportunity to point out places of historical interest to his young son.

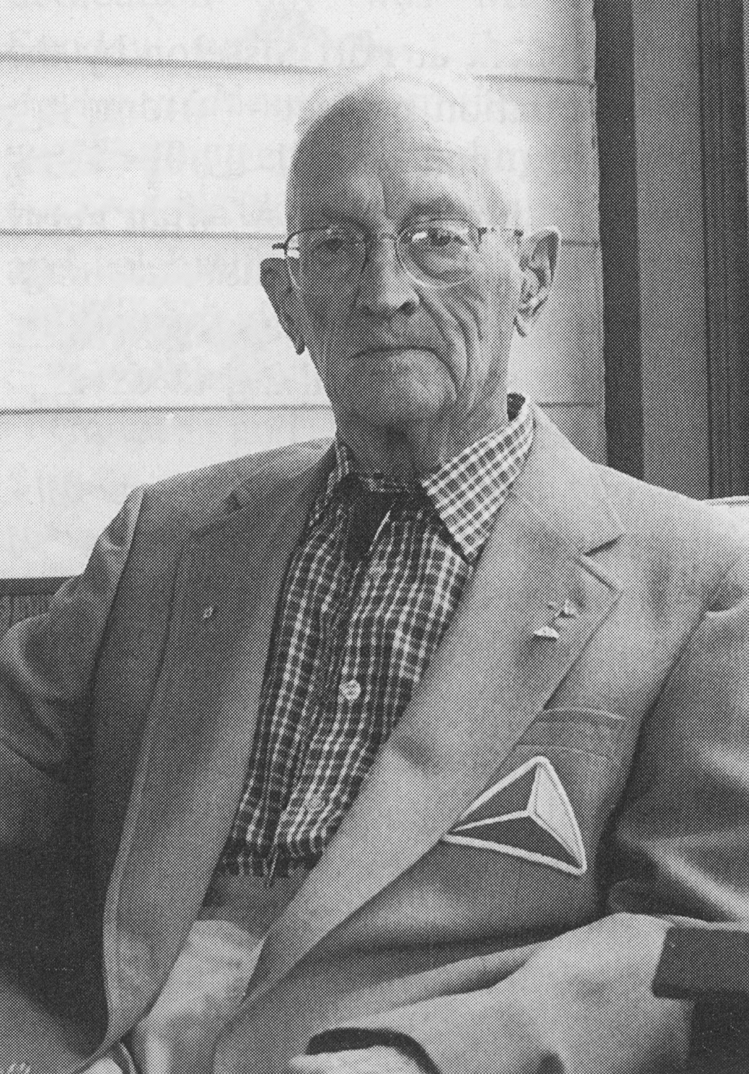

|

| Because of his efforts to save the outpost in northeastern South Dakota, Robert Perry earned the nickname "The Fort Sisseton Kid." |

Perry remembers well that trip to Fort Sisseton. "There was a hunting party from Chicago," he says. "Some guy from London had shot a lot of ducks, or maybe somebody else had shot them for him, Lord only knows. But he was thrilled and buying drinks. I got licorice and nothing else!"

After the U.S. Army abandoned Fort Sisseton, ownership was transferred to the state of South Dakota. (At closure, the post consisted of 22 brick, stone, frame and log buildings, settled on a military reservation of 82,112 acres.) The National Guard used the facility briefly, but by the second decade of the 1900s it was leased out for agricultural and hunting purposes. Through the 1920s, when Perry first visited, the leaseholder was Colonel William D. Boyce, owner of the Chicago Tribune and founder of the Boy Scouts of America.

Though Perry was on the grounds several times in the 1930s, years when the Works Project Administration (WPA) restored many of the fort's tumbledown buildings, his role as defender of the post began in earnest in 1953. That's when he moved to Britton, 18 miles northwest of Fort Sisseton, to become the local manager for Northwestern Bell Telephone.

"We had a line out there at the fort," Perry says, "so I went and checked it." When Perry arrived, there was a No Trespassing sign on the gate, but over he climbed anyway. "The leaseholder rode up on his horse and he shouted, 'You don't read very well!' I yelled back, 'You see that telephone truck there? I'm going in to inspect my line."

What the young telephone manager saw shocked him. "The guy who was leasing the fort for $75 per year wasn't supposed to be using the buildings," Perry says. But the hospital building, one of the main structures, was filled with sheep, and the other buildings were also being misused. "So we got into a fast argument," he says, "because I don't mind tangling with anybody."

By the time this scrap and its aftermath had passed, Perry and a friend from Britton maneuvered the lease from the state for themselves. When the former tenant complained that they had no livestock, Perry replied, "We've got 175 head of deer grazing out there, and we're expecting some antelope," claiming the wild animals as his herd to justify the contract for agricultural usage.

Barely 20 years after thousands of man-hours and many federal dollars had been spent at Fort Sisseton by the WPA restoration project — including, inexplicably, coating all the building interiors with pink paint — what Perry found in the 1950s was disheartening. A historical treasure was crumbling, and no one seemed willing to do anything about it.

No one but Robert J. Perry, a firm believer in public service. While serving as telephone manager in Frederick during the 1940s, Perry raised the money for new fire equipment, set up a rescue unit and established a mutual fire aid association. In 1951, he saved the life of a young boy following an accident and earned a company citation for his quick action.

"If a town is not a better place for my having lived in it," Perry says simply, "then I'm not worth very much, am I?"

But even Perry's service ethic had its limits. In 1959, when his fellow citizens in Britton tried to draft him to run for mayor, he flatly declined. "That's where I draw the line," he told a reporter. "I wouldn't get mixed up in politics for anything.”

|

| The barn is one of many buildings saved through Perry's efforts. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

What makes that quotation so ironic is that Perry played politics like a master to create the future for Fort Sisseton that he had in mind. First he convinced his fellow members of the Britton Lion's Club that this was a project worthy of their attention. (Perry was president of the local chapter.) Then he worked to build support from the larger community and began correspondence with South Dakota's governor, Joe Foss.

"I left a number of petitions with your secretary on Tuesday," he wrote in 1958. "These petitions asked that Fort Sisseton be made a state park. You can see by the number of names that the people of this area are very concerned." He also invited the governor to speak to the Britton Lion's Club.

Joe Foss understood politics, as well. He wrote back saying he had spoken to the Game, Fish & Parks Commission about Fort Sisseton, and turned the petitions over to the South Dakota Legislature. He even promised to visit Britton, and Perry recalls those days fondly. "Joe (Foss) was a good guy," he says. "He listened to what I had to say."

Things moved quickly after Perry and the Lion's Club got the governor's attention. Foss spoke on April 23, 1958, at Britton 's Masonic Temple, and at the end of May a legislative subcommittee on the future of Fort Sisseton scheduled a public hearing for June 2.

There was just one glitch. "The subcommittee wanted to meet in Pierre, but I didn't want to meet there," says Perry. "I wanted them out at the fort."

Those planning the meeting objected that the outpost had no suitable facilities — no heat, no lights, no furniture, or anything else. Standing firm, Perry was able to sway the decision on the meeting location, but he had only from Monday to Wednesday to make acceptable arrangements.

"It was a good thing I was the telephone manager," he remembers, "because I got on the phone and called a lot of people. At the time, I was the head of the county search and rescue squad, and I had a big generator. So I knew I had lights. It was also big enough if we needed heat. I called the Veterans' Club and got tables and chairs."

|

| The North Barracks now houses a visitors center and replicas of the frontier soldiers' accommodations. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

"We met in the little library building at the fort, and after all my phone calls, it was chock full." Many notables were in attendance, including two state legislators from Britton, Sen. Arthur Jones and Rep. Elden Arnold, the community's mayor and the presidents of nearly every organization in all the surrounding towns. Jones and Arnold led the testimony with statements of support.

Then Perry took the floor. He recalled for the subcommittee the thousands of signatures on petitions, and reported that informal registers at the fort had recorded visitors to the site from 46 states. "Few historical spots between the Great Lakes and the Rockies can compare," he bragged.

After hearing Perry out and a tour of the structures and grounds, the subcommittee voted to recommend, "that the area at Fort Sisseton including all buildings located both inside and outside the moat be established as a state park." Further, they recommended that a full-time caretaker be located at the site.

In early 1959 the South Dakota Legislature turned those recommendations into law. There was a different governor by then, Ralph Herseth, and Perry wasn't about to let the issue die on the new chief executive 's desk. "Now that both the House and the Senate have passed House Bill 677, it looks like our dream is at last in your hands," he wrote to Herseth. "We hope that you, as governor, are willing to sign the bill making Fort Sisseton into a state park."

"We are at present planning a brochure on Fort Sisseton State Park in which we would like to have a letter from you," he went on, subtly playing his trump card. "We should be able to attract additional tourists to South Dakota and our historic Lake Region."

Herseth signed the bill and sent a letter for the brochure in which he announced the creation of the new Fort Sisseton State Park. In his message, the governor also commended the efforts of the Britton Lion's Club and other public-spirited individuals, "to preserve for posterity this dramatic reminder of a colorful era in the history of Dakota Territory." When the state park was dedicated on July 26, 1959, Gov. Herseth was the main speaker, with Robert J. Perry as master of ceremonies.

|

| Re-enactors demonstrate the firing of Civil War-era cannons during Fort Sisseton's annual summer celebration. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

Among the others present on that dedication day was Max Cooper, Sunday editor for the Aberdeen American News. From then on Cooper regularly used his column, “Jottings from the Dakotas,” to promote events and celebrations at the new state park, which helped immeasurably in getting it established.

Cooper and Perry became close friends, with the latter making regular appearances in Cooper's column. At first the writer referred to Perry as "Mr. Telephone," but soon he began writing about a mysterious fellow known only by the sobriquet, "The Fort Sisseton Kid."

"The Fort Sisseton Kid, who just naturally hates to think about anyone's telephone going unused, rang me up last week to tell me what he had on his mind," Cooper wrote on one occasion. "(He) mentions that I might want to go along on this trail ride. He has heard that I recently have run 100 miles and he says I can go either as a rider or as a horse — take my choice."

Beneath the bantering humor laid a respect for what each had done to make the state park a success. "The accomplishments of Max are many," Perry wrote when Cooper later left the newspaper. "Without his stories and pictures, I feel that the old Fort Sisseton would still be a pile of rubble, overgrown with weeds."

Having accomplished such a lofty goal, Perry was not about to rest contentedly on his laurels. During the 1960s he convinced yet another South Dakota governor, Archie Gubbrud, that the historic outpost deserved attention. The governor sent prisoners from the state penitentiary to the fort to work on restoration projects, often under the supervision of Perry himself.

With only shovels and chutes, Perry and his crew filled an entire basement — 9 feet deep by 148 feet long — with gravel brought by the truckload from a nearby pit, thus preventing the walls of the officers' quarters from collapsing. Perry cut a deal with the pit owner for 25 cents per truckload, because, as he recalls, "We could get that kind of money."

Gubbrud also visited the fort at Perry's invitation. It was a hot day, and the governor got filthy from dust flying through open car windows as he drove the dirt and gravel road leading to the state park. Never one to miss an opportunity, Perry planted the seed of an idea when the governor complained that he didn't look presentable. Not long after, Gov. Gubbrud arranged funding to resurface and oil the road.

The story of Fort Sisseton can now be found in the preserved-for-posterity buildings of the outpost itself. But the story of Fort Sisseton State Park can be found in the scrapbooks that Perry, The Fort Sisseton Kid, donated to the park.

Along with various documents and photographs, there are letters to and from the powerful in South Dakota's last half-century: U.S. Senators Karl Mundt, Joe Bottum and George McGovern, U.S. Representative Ben Reifel, several governors, and even U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. They are tangible signs of the effort Perry put forth to make the park a reality, and a testament to the political skills of a fellow who, "wouldn't get mixed up in politics for anything.”

Editor’s Note: John M. Hilpert served six years as president of Northern State University in Aberdeen. He is currently president of Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi. This story is revised from the September/October 1998 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments