The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

“Very Hard Traveling”

Apr 3, 2019

|

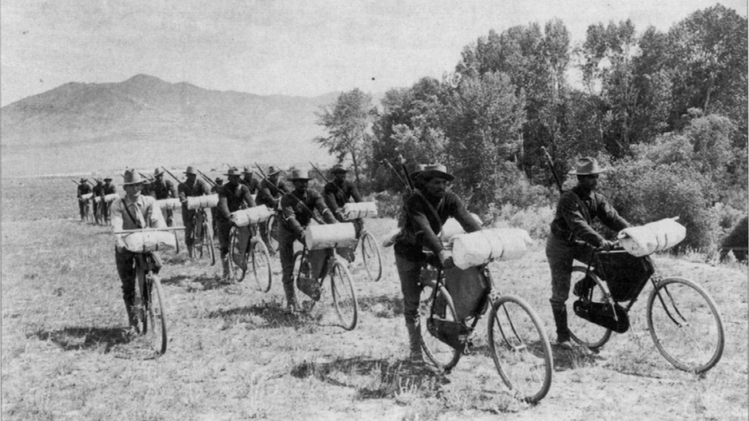

| The 25th Infantry U.S. Army Bicycle Corps in the badlands of Montana. |

If you happened to be working in southwestern South Dakota in July of 1897, you might have spotted an unusual sight: the first organized American mountain biking expedition. The soldiers of the 25th Infantry U.S. Army Bicycle Corps were on their way from Missoula to St. Louis, a 1,900-mile expedition designed to test the idea of bicycle-as-combat-vehicle.

On July 2, the Buffalo Soldiers — the colloquial name given to segregated, all African-American military units — covered 54 miles between Clifton, Wyoming and Rumford, South Dakota.

Blogger and Wyoming middle school social studies teacher Mike Higgins has compiled a day-by-day travelogue from contemporary newspaper stories and the journal of Second Lieutenant James Moss. E.H. Boos, The Daily Missoulian's embedded reporter wrote, "At S&G, the first station in Dakota, we filled our canteens with some of the worst water we had yet used. From the latter place to Edgemont the road, mostly sand, made very hard traveling. At Edgemont we stopped for lunch and departed soon after. Struggled against dust, heat and vast fields of prickly pear that morning, stopped in Edgemont for lunch, and departed soon after. Good roads, although hilly, were met, we were able to go at a good rate and were at Rumford, 16 miles from Edgemont before sundown."

|

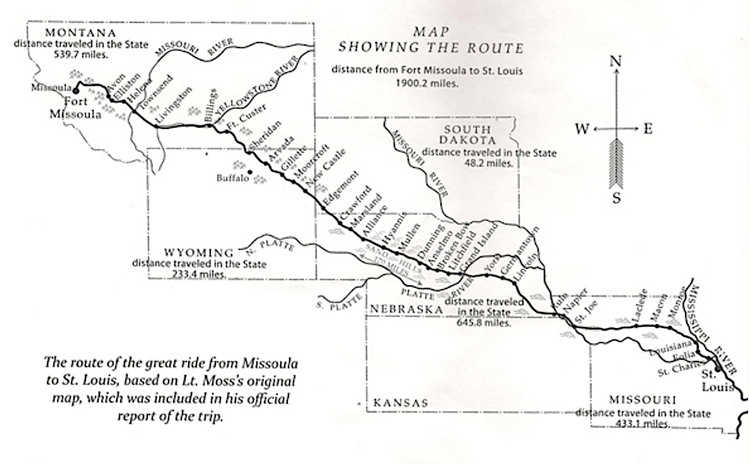

| A map detailing the 1,900-mile journey. |

The Corps crossed into Nebraska the following day, reaching Crawford as, "the Fourth of July celebration was at its height," Boos wrote. "The town was full of people and the corps was given a hearty welcome." After they were dined and entertained by revelers and soldiers from nearby Fort Robinson, the corps "left the town, passing through the big crowds on the main street amid loud cheers." They camped that night in Belmont.

Their time in South Dakota had been strenuous and short. Just 48 of their 1,900 miles unwound across our state. Good drinking water was hard to find. Wheels sunk deep in dust on sun-parched ruts, and on reaching Rumford, "a section hand … advised us that the nearest camping place was at a ranch a mile and a half further on," Boos wrote. "We started out and traveled five miles before reaching the ranch. A madder set of men never lived than the bicycle corps when we finally did get a camp.”

Cycling was already enormously popular in late-19th century America and Europe, but bicycles weren't generally thought of as all-terrain vehicles. European militaries experimented with bicycle units with mixed results. The longest-lived was the Swiss Cycle Regiment, founded in 1891 and retired in 2001.

In the U.S., Gen. Nelson Miles was aware of European experiments and advocated for the metal mule. "The bicycle requires neither water, food nor rest," he wrote. "The rider may push to the top notch of his own endurance without thought of his steed."

When Second Lieutenant James Moss graduated at the bottom of his class at West Point in 1894, he was assigned to the 25th Infantry in Missoula. (Moss was white, like all officers placed in charge of otherwise all-black units). Moss quickly boarded the tactical cycling train and sought volunteers for a cycling corps. His first crew successfully completed several experimental forays, including an 800-mile round-trip trek from Fort Missoula to Yellowstone National Park.

Army leadership was divided on the utility of the military bicycle, so Moss devised an epic journey, hoping to silence the doubters. The 1,900-mile expedition from Missoula to St. Louis would cross terrains from, "the mountainous and stony roads of Montana; the hummock earth roads of South Dakota; the sandy roads of Nebraska and the clay roads of Missouri," he wrote. For this mission, he assembled a team of 20 men and ordered custom-designed Spalding bicycles to carry their weapons and gear. The men trained for two weeks and embarked on June 14, 1897.

|

| The soldiers encountered rough traveling during their brief time in South Dakota. |

The roads they followed were anything from wagon trails to game trails to railroad track beds. They often had to dismount and walk for miles, their bicycles loaded with rations, rifles, ammunition, spare parts and gear. They averaged about 52 miles per day, facing their toughest test in the sandhills of Nebraska. They became experts at patching tires.

At journey's end, Moss told the St. Louis Dispatch that, "The trip has proved beyond peradventure my contention that the bicycle has a place in modern warfare. In every kind of weather, over all sorts of roads, we averaged fifty miles a day. At the end of the journey we are all in good physical condition."

The onset of the Spanish-American War brought an end to Moss' experiments in military cycling. In the summer of 1898, the 25th Infantry — and all four of the Army's all-black units — distinguished themselves in battle in Cuba. As with the other African-American units, their centrality in pivotal battlefield moments was often erased when mythologized versions of the War became popular lore.

There's one accomplishment no one ever tried to strip from the 25th — the Missoula-to-St. Louis mission, perhaps because there was no competition. Nobody before or since has matched the Bicycle Corps’ journey.

Pferron Doss, author of a historical novel about the Bicycle Corps, led a commemorative journey that retraced their route in 1974. "We thought once we reached the Continental Divide, it would be downhill all the way," Doss says, "but that wasn't the case. But it's a trip that every last one of us will never forget, because it was a time in our lives that we felt very proud to be doing this in their honor.

"It had not been done before, and these were black soldiers who formed a very unique first-time group. That in itself gives you a sense of, not only responsibility, but the freedom to feel very proud of what you're doing."

Michael Zimny is the social media engagement specialist for South Dakota Public Broadcasting in Vermillion. He blogs for SDPB and contributes arts columns to the South Dakota Magazine website.

Comments