The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

What About Doc?

|

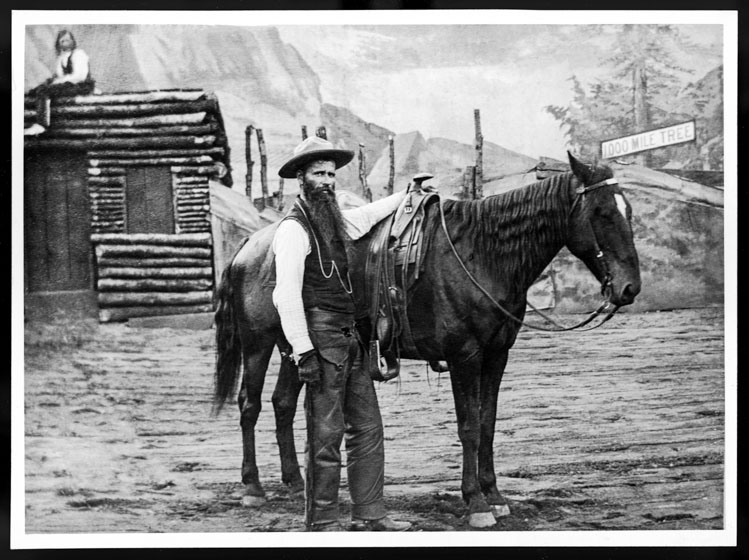

| Doc Middleton was a Nebraska outlaw who gravitated northward to run saloons in southwestern South Dakota. His exploits included running in the 1893 Chadron to Chicago horse race, where he was pictured at the finish line. |

TO BE CLEAR, Doc Middleton never earned a doctorate. Sometimes it seems that’s the only thing we know for certain about the outlaw.

Middleton spent considerable time in western South Dakota, first arriving nearly 150 years ago and variously described as horse thief, cattle drover, saloon keeper, murderer, sheriff and wannabe showman. For what it’s worth, he possessed one of the Old West’s best beards. In early photos, his facial adornment — maybe a foot long — could have made him the front man in ZZ Top. After it grayed, Middleton trimmed it; he then bore a resemblance to Buffalo Bill Cody.

In the Black Hills, a place long fascinated by notorious men like Wild Bill Hickok, Lame Johnny, Fly Speck Billy and even George Armstrong Custer, it seems as if Doc Middleton has fallen through the cracks. Not that he’s been completely forgotten. Look up Ardmore, South Dakota, on Wikipedia and you’ll see two people noted as playing roles in local history: President Calvin Coolidge, who visited in 1927, and Doc Middleton, “a former resident who was an infamous outlaw.”

What made Middleton an outlaw? It’s hard to top murder. He was indicted on that charge after shooting an Army private in 1877 during a dance hall brawl in Sidney, Nebraska. The charge never went to trial, says Rapid City writer Scott Lockwood, whose new book Alias: Doc Middleton, attempts to bring the somewhat mysterious Middleton back into the public consciousness. Horse-stealing did put him behind bars on several occasions.

Middleton’s thieving began at age 14 in his native Texas. One theory about his nickname is that he developed skills for “doctoring” horse brands. Or it could have stemmed from a sloppy signature with the initials for David and Charles scribbled together and mistaken for Doc. David and Charles, by the way, were not his actual first and middle names. He stole them. And Middleton, at birth, was a middle name and not his surname. His last name was Riley. Records show Doc was born in the Texas Hill Country, though he sometimes claimed Mississippi as his birthplace.

|

| Rapid City author Scott Lockwood was introduced to Doc Middleton through his fascination with the town of Ardmore. Lockwood's new biography traces the outlaw's life as well as his connection to the Fall River County ghost town. |

Doc’s life was so full of contradictions and outright lies that writing a book-length biography would challenge any author. But Lockwood embraced the historical detective work. As he was researching, Lockwood was asked if he liked Middleton. No, Lockwood replied. He can’t condone murder and won’t minimize it. He suspects the Sidney incident wasn’t the only time someone died due to Middleton’s violence. On the other hand, there were certainly not dozens of killings, as some exaggerated newspaper stories of the era claimed.

“For a while I didn’t really understand how bad horse stealing was in the 1800s,” Lockwood says. It deprived a person of transportation, perhaps their livelihood, and sometimes their closest companion. Some of Middleton’s early thefts may have been particularly nasty, taking animals from Oklahoma’s Indian Territory because he believed authorities wouldn’t pursue or prosecute. It’s possible he followed the same line of thinking on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations in Dakota.

Lockwood was born in Huron and graduated from Custer County High School. He wasn’t particularly curious about history classes in school but, he says, “I was always interested in the stories about the ‘old days’ my elderly relatives and neighbors told me.” He worked for railroads throughout the country’s midsection, making and supervising track repairs, and eventually managing sections of Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s maintenance from Montana to Texas, and from Alabama to Illinois. When Lockwood retired, he came home to South Dakota and its “rhubarb and lilacs.”

Ardmore interested him in ways similar to the stories his older relatives and neighbors had recounted decades earlier. Virtually a ghost town now on the South Dakota-Nebraska line, south of the Black Hills, Ardmore similarly attracted Middleton in 1900. He bought town lots, served as sheriff for a while and owned a saloon. He may have failed in the liquor business in another town, Lockwood thinks, but by the time he arrived in Ardmore he had learned not to drink his profits.

Lockwood first learned of Middleton by reading the Wikipedia post linking President Coolidge and the horse thief. “I guess I was intrigued with him because he chose to make tiny Ardmore his home,” Lockwood says. And “he was able to steal hundreds of horses and escape vigilante justice.” Vigilantes operated outside the law, often lynching horse thieves and cattle rustlers in the Old West, including Middleton’s Nebraska partner-in-crime, Kid Wade. Middleton may have considered vigilantism more criminal than anything he perpetuated.

“He was such a restless man,” Lockwood says. “He liked to see his name in the newspapers and became a folk hero to many. He was great at promoting things he believed in.”

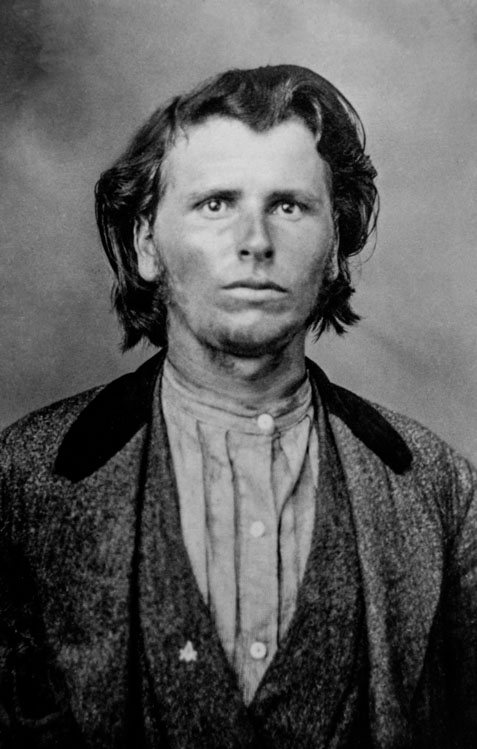

|

| This is the earliest known photograph of James Middleton Riley, later known as Doc Middleton, taken around 1871 when he was 20. |

Middleton obviously believed in Ardmore. But what he really wanted to promote was his own Wild West Show. There are stories claiming he performed briefly in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Maybe he did and maybe he didn’t, but Lockwood thinks Buffalo Bill Cody didn’t care for Doc Middleton. In Middleton’s mind, his own show, actually incorporated in 1904 in Rapid City, would be no less an extravaganza than Buffalo Bill’s. But it never happened. If it had, Middleton could have woven in plenty of his own real-life adventures: rounding up wild cattle roaming Texas after the Civil War, then becoming one of America’s original cowboys who drove herds north for public domain grass and less bovine disease. He rode through Kansas and Nebraska (the state that’s done the most to document Middleton’s outlaw history) and in 1877 he made it to the Black Hills, according to Lockwood. Middleton spent time in early Custer and Deadwood and was particular about whom he claimed as a friend or associate. Calamity Jane? “She ain’t my kind of people,” he reportedly said.

There’s an adventure the public would no doubt have demanded be recreated in abbreviated form as part of a Doc Middleton Wild West Show. That was a thousand-mile horse race from western Nebraska to Chicago in 1893. A Chadron, Nebraska, man promoted the idea as a hoax in an era of elaborate hoaxes nationally — ones that newspapers often reported, winning national attention for a community. In part, the news of a super-sized horse race spread because the idea appalled humane societies, and they took action to stop it. Middleton announced he would compete, and the Deadwood Pioneer Times entered into jokey reporting by remarking he should be ineligible because he would surely end up stealing other racers’ mounts.

Then remarkably, driven by the publicity, the race began to be taken seriously. In fact, humane organizations inadvertently boosted the competition when they said they would supply representatives to monitor animal health along the route. Middleton did, indeed, ride the distance on a gelding called Jim Fisk. Some observers predicted a win for Middleton. Strangely, Lockwood says (or maybe not so strangely when you consider the strong-willed contestants), the race didn’t begin until 6:15 one evening because of an argument over eligibility. The date was June 13, 1893. John Berry, riding a horse from Sturgis called Poison, first reached Buffalo Bill’s Wild West grounds near the Chicago World’s Fair on June 27. Berry wasn’t declared the winner, though, because in Chicago the eligibility issue flared again, and Berry had played a role in selecting the route, giving him an unfair advantage. Middleton finished about 27 hours behind Berry. Of eight riders who completed the long course, Middleton came in sixth.

Newspaper accounts of Middleton’s participation in the thousand-mile competition likely surprised some people. Reports of his death had circulated numerous times over the years, usually owing to gunshot wounds but once due to smallpox in Ardmore. It was as if the press was certain that Middleton would meet death at an early age and was ever ready to pounce on the news. While Middleton liked newspaper stories, even those maudlin and false reports, he had no use for anyone proposing a book about his life. He wanted that writing assignment reserved for himself, although he never got around to it.

“He even threatened to come after anyone attempting to write a book,” Lockwood says.

|

| The Middleton family in 1899 included (from left) Doc; children Joseph William, Ruth Irene and David Wesley; and his wife, Irene. |

Middleton married three times. In 1911 his third wife, Irene, died at Hot Springs after gallbladder surgery. Funeral services were conducted in Ardmore and then her body was interred about 30 miles south in Crawford, Nebraska. Certainly that’s where Middleton believed he would someday be buried, in prime horse country. Crawford sits a short canter from Fort Robinson, a major base of operations for the U.S. Cavalry during Middleton’s time.

But Middleton never made it to Crawford. He was occasionally involved in unauthorized alcohol sales and that landed him in jail in Wyoming in December of 1913. He died on December 27 at age 62 from a bacterial infection complicated by pneumonia. A burial plot at Douglas, Wyoming, was supposed to be temporary, but it’s where Middleton lies 112 years later. In 1968 a group of Nebraskans petitioned to move the body but didn’t gather many signatures. Lockwood, during his railroad career before he ever heard of Doc Middleton, lived in Douglas just blocks from the gravesite.

Knowing the geography of Middleton’s life was a plus for Lockwood in writing this book. So was newspapers.com, which allowed for electronic access to papers that Middleton knew and admired. “Sometimes I’d be so excited about what I found that I couldn’t stop at dinner time,” Lockwood says. “Other days I’d walk away and not care if I ever looked again.”

Such mixed feelings are to be expected about a man as conflicted as Middleton. Readers who love Western lore and the Black Hills — and are eager to rediscover a man nearly lost to history — will be glad he stuck with it.

Editor’s Note: Contact Scott Lockwood at b735198@gmail.com to purchase a book or to schedule an author talk. This story is revised from the March/April 2025 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Glad to see the work expanding!