The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Lady of Justice

|

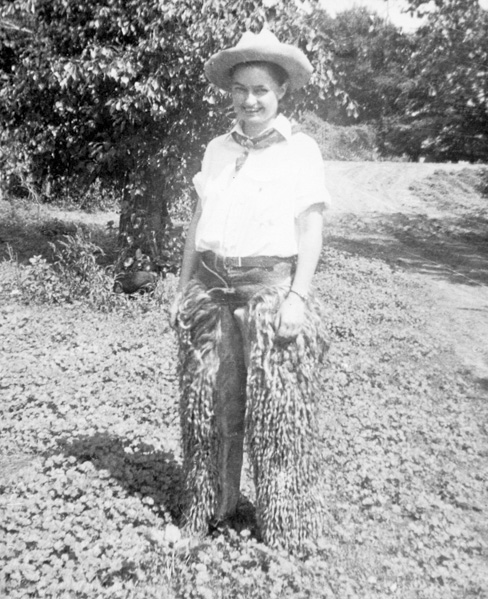

| Mildred Ramynke in 2004. |

Editor's Note: The Hon. Mildred Ramynke passed away Sept. 7, 2013 at age 96. To pay tribute to this remarkable woman, we wanted to share this story, which originally appeared in the July/August 2004 issue of South Dakota Magazine.

Dressed in judge’s-robe black slacks and jacket relieved only with a flash of brilliant coral at the neck, 87-year-old Mildred Ramynke told her story — an incredible story of firsts — as if it was no big deal.

To her, it wasn’t.

Trick roper (she taught herself to twirl three at once), pilot (the only woman in her class), flight instructor (solo again), and finally, judge (you’ve got it — South Dakota’s first woman circuit judge), Ramynke said simply, “I just felt like I was doing what I was supposed to do.”

This tiny woman — though no one mentions her size — tilled a wide furrow across northeastern South Dakota’s legal landscape, winning the affection and respect of those she worked with, those she lived with, and even those she sent to jail.

Chief Justice David Gilbertson, who brought his first cases to Ramynke’s courtroom, said she was the biggest influence on why he became a judge. “I saw the good that she was able to do,” he said, adding that Ramynke resolved disputes as peacefully as she could and still retained the community’s respect for the court system. “I don’t have too many heroes in this life, but she’s one of them.”

It all began on what is now the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, where her parents, Harrison and Alta, homesteaded. Mildred was their only child, born in 1917. By the time she was walking, she could ride a horse. “Riding horseback was just a way of life,” she said, “especially when we lived West River.”

When Mildred was eight, the family moved to Wisconsin to farm, but they returned to South Dakota after Mildred finished eighth grade. They bought land in the hills of Agency Township on the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Reservation, where they raised livestock in the foothills.

There were no school buses and no car to drive to town, so Mildred lived with her aunts’ families in Watertown while she finished high school. In summers she helped on the farm, putting up hay and riding the fences. And she got involved with Whipple’s Rodeo, five miles down the road.

|

| In her youth, Ramynke was a cowgirl and rope artist. |

“My dad got together with him, and he did a lot of his promoting and became an announcer for the rodeo,” Ramynke remembered. Nobody planned on her joining the show, but she learned trick roping to make herself useful.

“[Roping] is one of those things you kind of grow up with,” she said. Watching the cowboys, she taught herself to jump in and out and through the spinning rope. She learned the butterfly and how to twirl three ropes at once — one in each hand, the third in her mouth.

But at age five, she had set her sights on law school. “It never dawned on me I’d do anything other than that,” she said. “I wanted to be a lawyer.” The fascination was born when Ramynke’s dad, looking for entertainment on remote Standing Rock, went to town, watched trials, then came home and acted them out. “To me, they were the big heroes, the attorneys,” Ramynke said.

She finished two years of pre-law in Brookings, and three years later, she and Margaret Crane were the first two women to graduate from the University of South Dakota Law School. Both were admitted to the bar in 1939. “There weren’t many people looking for a woman lawyer,” Ramynke said. She took a collections job with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which was trying to sort out where the money had gone when banks closed during the Depression. “It wasn’t interesting,” she said, “but it was work.”

Her posting to Huron was the beginning of another adventure. It was six years before Pearl Harbor, but the Army wanted to train pilots, and began its Civil Pilot Training with ground school and 40 hours of flight instruction. Ramynke had her degree, but Huron College wanted more students in its program, so she learned to fly. “I’d never been off the ground before,” Ramynke remembered. “But I loved it, every minute."

She earned her private license and took a receptionist job at the airport with the promise of more flight training. “I kind of got used to being the only woman doing things,” she said. That’s also where she met Cliff Ramynke, a flight instructor; they were married in March 1941.

When Cliff landed a job at Iowa Wesleyan University to train men in the Army Air Force, Mildred, with her flight instructor rating, taught young men to fly. She loved working with cadets and learning the maneuvers, including stalls and spins. “We weren’t teaching them to do loops, but whenever we had a little free time, we’d do them just for the fun of it,” she said.

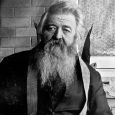

|

| During World War II, Ramynke joined the WAVES, Women Accepted for Military Service. |

When Cliff went into the military, Mildred joined the WAVES, Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, only to be assigned to aerographers school to learn meteorology. She was sent to Washington, D.C. to work in Naval Intelligence, where aerographers used their weather training and Japanese weather reports to try to break the Japanese codes.

At the end of the war, the Ramynkes returned to Roberts County. The couple had three daughters, and Cliff worked with Mildred’s dad raising registered Hereford cattle. In those days, every county had its judge, but the Roberts County judge was elderly. Seeking a replacement, local lawyers came to Ramynke, who hadn’t opened her law books since she left college. “It wasn’t that they thought I’d be so smart or anything,” she remembered. “They just needed a warm body.” Besides, she said, none of the lawyers wanted to give up lucrative probate work to become a part-time judge. She won by a landslide, and took office in 1958. W. R. Brantseg, elected Roberts County states attorney that same year, said he never expected a pushover. “And we soon found out she sure as heck wasn’t.”

In court, Ramynke found her second home. While she handled probate, civil cases and mental illness, juvenile work was her forte. Kids from 10 to 18 came to her court, mostly for burglaries or alcohol violations, but not many violent crimes. Judge Ramynke tried to figure out how to help them.

Ramynke even looked after the ones whose families couldn’t do it, such as a 12-year-old who ended up in Ramynke’s courtroom. The boy’s dad was in jail for drinking when the boy was picked up. His mother’s younger brother, who had a history of trouble, had taken the boy along for a burglary. By the time the boy came to court, his mom was also in jail for drinking.

“It was pretty obvious there wouldn’t be anyplace he could go after he’d been in court,” Ramynke said, so she reluctantly sent him to the Plankinton training school. When no one visited him, she sent him letters. When no one sent him clothes, she did. When he was ready to be released, the parents’ situation had deteriorated, and Ramynke placed him with an aunt. “He turned out OK,” she said, and he still visits her.

“That was the good part about it,” Ramynke said, “getting involved.” In those days, judges had more discretion, she said. People were more concerned with children being treated well and learning right from wrong. “Now there’s more of that put-them-away-and-throw-away-the-key.”

|

| Ramynke posed with one of her students in her flight instructor days. |

Brantseg figured he and Ramynke learned the law together. “You learn not only by the books but by doing,” he said, calling Ramynke a good student and exceptionally bright. He’s not alone in saying Ramynke was always willing to listen — to everybody — and that she was fair to everyone, a virtue in a multicultural corner of the state.

Having built a reputation as county judge, a decade later Ramynke became district judge for Roberts, Day, Grant and Marshall counties. In 1974, when voters approved the State Unified Court System, she ran in a field of five judges for four Fifth Circuit Court positions. She came in second, and in 1975 was sworn in as South Dakota’s first woman circuit court judge. The circuit included Aberdeen, Sisseton, Mobridge, Redfield and Faulkton. Ramynke’s new job was full-time.

“She was an honorable judge,” said Long, who was Roberts County Sheriff from 1975 to 2003. He remembered a judge he could visit any time he wanted, one who took more time than most to interview witnesses to understand what was up.

“She’s one of these you can learn a lot from,” said Vivian Hove, who went to the Roberts County Clerk of Courts office just out of high school and later was elected to the office. “She never put herself above other people.” One of the things Hove remembered best was that Ramynke didn’t let anybody take advantage of her. When defendants told outrageous stories — about finding alcohol under a tree or along the road, for example — Ramynke let them know she wasn’t going to buy a lie. “I think that’s why she was so well liked,” Hove said. “She used wisdom, good common sense.”

Gilbertson met Ramynke in 1975, when he returned to Sisseton to practice law. He was still a young prosecutor the day Ramynke stopped court and sternly asked to see him immediately in the back room. “I thought she was angry at me,” Gilbertson remembered. Instead, the judge said, “That kid’s got a gun on him. You can see the bottom of the holster sticking out of his jacket.” Gilbertson figured he could take the gun away, but Ramynke called the sheriff. The deputy agreed to come in the back door; Gilbertson went back in the front. They jumped the boy and found a hunting knife in the holster. Gilbertson credited Ramynke for sentencing the boy only on the original charge, not penalizing him for the crime of stupidly carrying a knife into the courtroom. “She always kept her cool on the bench, was very fair to everybody, very polite,” Gilbertson said.

|

When she saw alcohol-related crimes, she always tried to include alcohol treatment in the sentence. When she saw kids, she’d try to educate them on where their misdeeds were heading them and what they needed to do to turn their lives around. She’d tell them she had full confidence they could make successes of themselves, and some of those speeches even choked up Gilbertson, who said he wished he could’ve recorded them.

Being a woman had nothing to do with Ramynke’s success, those who encountered her said. She earned respect.

Besides her many firsts, Mildred Ramynke was honored often, including induction into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 1987. Looking back her life, Ramynke was one of those rare people who have no regrets. “I was fortunate to have opportunities to do all these things, because I enjoyed every minute of it,” she said. “Everything I’ve done I would have done if I didn’t earn a penny.”

Comments

funeral in Peever Lutheran on Monday was a nice tribute to a great lady